To Survive on This Shore: Photographs and Interviews with Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Older Adults, currently on display at the McKinley Foundation’s Artists’ Alley through the end of October, is a lesson in excavation. A revolutionary collaboration between photographer Jess T. Dugan (they/them/theirs) and social worker and gender studies scholar Vanessa Fabbre (she/her/hers), To Survive on This Shore addresses the hard truth that “representations of older transgender people are nearly absent from our culture and those that do exist are often one-dimensional.” Since its arrival in C-U, To Survive on This Shore has taught us the importance and the impact of community exhibitions.

While physically installed at Artist’s Alley, its concept, as well as its creators, have engaged with academic audiences at The University of Illinois’ Center for Advanced Studies and Spurlock Museum as well as community members at its opening reception and book signings. This duality is baked into both its creation and its outcomes, which seems right for a project which, in every way, seeks to complicate assumptions and create space for new narratives. The community exhibition here in C-U travels throughout the nation as does its larger museum-oriented sister installation.

Photo from Jess T. Dugan’s website.

To Survive on This Shore emerged over the course of five years, during which Dugan and Fabbre sought “subjects whose lived experiences exist within the complex intersections of gender identity, age, race, ethnicity, sexuality, socioeconomic class, and geographic location, they traveled from coast to coast, to big cities and small towns, documenting the life stories of this important but largely underrepresented group of older adults.” While Dugan, a trans man, and extremely thoughtful portraitist, could seemingly take on this feat of photojournalism alone, the decision to collaborate with Fabbre, a social worker with serious academic cred in the gender studies arena, is significant.

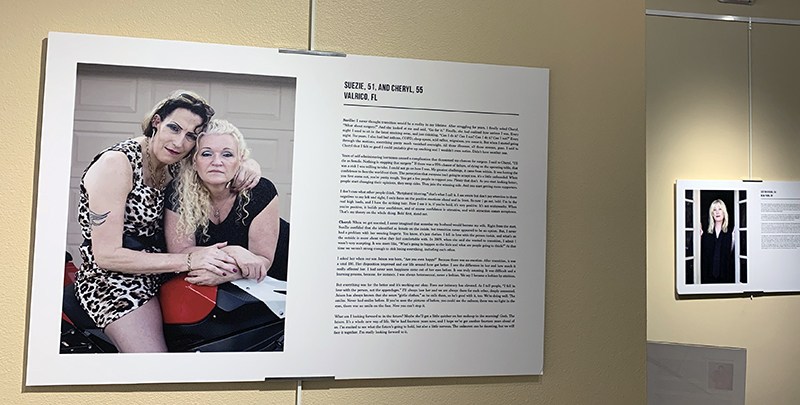

In its community exhibition format at Artists’ Alley, To Surive on This Shore, is intimate, both in terms of its space and content. Yet one can easily imagine Dugan and Fabbre mapping out their intersectional cross-country interviews with the tools of a team preparing for human-subject research, which in many ways they are. The trust that Dugan and Fabbre built is evident in the faces and words that surround the walls and stands as a testament to the power of this collaboration.

Photo by Debra Domal

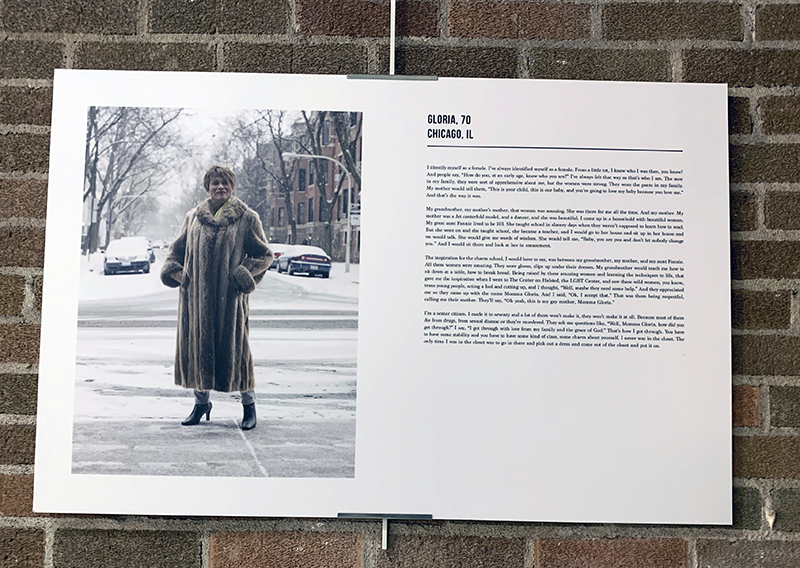

Housing an exhibition like this in a church adjacent building would seem wrong if that church were not McKinley, whose commitment to inclusivity has been long-standing. Standing before the much publicized images of Mama Gloria (directly above) and Dee Dee Ngozi (above Gloria) is like standing at an ancestral altar. As allies or trans and gender nonconforming descendents, we give thanks for sacrifices made in the trailblazing efforts to live one’s truth. We gain strength and joy and perspective. We recommit to the mission. We remember that the personal is political. And we remember that intersectional representation doesn’t just matter, it can save lives.

Ngozi’s narrative is in many ways the story of the relationship between faith, church, and the trans community. Her story is one of disrupting the church community-trans community binary. Told by an African minister “you’re Ngozi… It means God’s blessing. You have God’s blessing,” she took the word as her middle name to honor and embody its power.” Ngozi went on to co-found the first trans ministry in her church, where she “sat on the ‘mother board’ with all of the other ‘mothers.”

When the other mothers asked “What gives you the right to be here on this mother’s board? We don’t understand it,” Ngozi said this:

“Because I am the mother to the ones you can’t love. The ones that you cannot be a mother to, that you throw out on the street every day. Those are my children. The ones you throw away. That’s why I’m here.”

The mothers went on to accept her with these simple yet paradigm-shifting words: “Come on girl, sit down.” When we talk about how “love is love,” we need to underscore this nurturing kind of love, the kind that saves lives, and creates spaces for trans and gender noncomforming people.

To Survive on This Shore “encompasses “wide variety of life narratives spanning the last ninety years, offering an important historical record of transgender experience and activism in the United States.” The experience of standing inside this space is both intimate and epic. Part-time capsule, part confessional. And though our local community exhibition is just a slice of the history Dugan and Fabbre have midwifed into being, it provides a balanced view, a small, yet might chorus of voices. The portraits and narratives are each compelling and unique in their own right, but together they weave a complex and variegated fabric.

Photo by Debra Domal.

I conclude with Grace, pictured above, whose quiet, matter-of-face tone at first belies the significant internal and societal evolution she has lived through.

“In the ’70s they called me a faggot. In the ’80s I was a queen. In the ’90s I was transgender. In the 2000s I was a woman, and now I’m just Grace.”

Major props to everyone at the McKinley Foundation and The University of Illinois who brought this groundbreaking work to our town. I urge you to experience this exhibition in person while you can. And though the space may only allow a brief visit, its impact will remain with you forever.

To Survive on This Shore: Photographs and Interviews with Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Older Adults

Through October 31st

McKinley Foundation’s Artists’ Alley

809 S 5th St, Champaign

Monday through Friday, 9 a.m. to 4:30 p.m.

Learn more about Jess T. Dugan and the To Survive on This Shore project and book.