In March, Unit 4 administration made a recommendation to the school board to phase out self-contained gifted classrooms in elementary schools in favor of expanding access to more rigorous learning to all students. Prior to this year, all 1st grade students were tested using the Cognitive Abilities Test to determine if they qualified for admittance into the gifted program. Those who accepted that admittance would then attend grades 2 through 5 in classrooms exclusively for gifted students. The decision to phase out the program will have no bearing on students who are already enrolled, but no new classes will be added, beginning with the 2021-2022 academic year.

When we reached out to Unit 4 about this decision, they said:

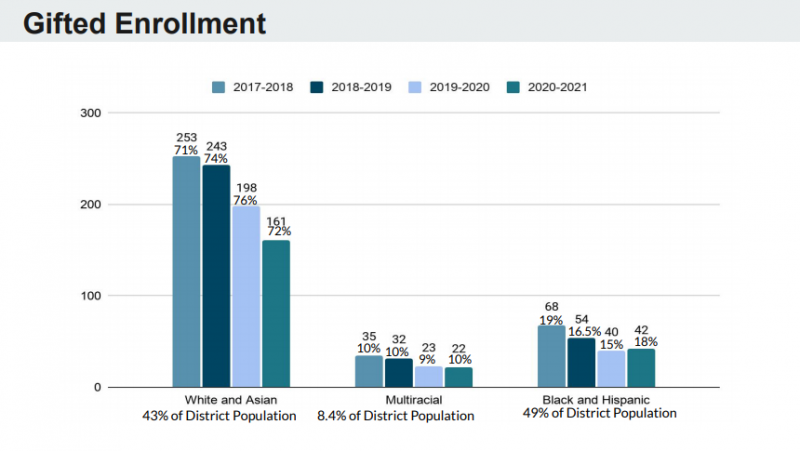

“Enrollment in gifted classrooms continues to trend down, and the makeup of the classrooms continues to represent a limited group of students that is not reflective of the diversity of the district. Unit 4 convened several task forces over the last twenty years to support more equitable enrollment in our self-contained gifted program. The most recent task force focused on equitable identification processes and teacher professional development opportunities, specifically around grouping students based on multiple criteria, developing highly engaged classrooms, and differentiated instruction. Even with these recommendations, our program remained discrepant in its enrollment.”

We agree that reimagining gifted education in Unit 4 is warranted. It’s possible to create an inclusive classroom environment that provides innovative and challenging learning experiences for students of all abilities.

Screenshot from Unit 4 Teaching and Learning Board of Education presentation.

Currently, self-contained gifted classrooms exist at four elementary schools: Booker T. Washington, Dr. Howard, Kenwood, and Stratton. Garden Hills has housed gifted classrooms in the past. Per Unit 4’s presentation, there are 225 students enrolled in gifted programming for the 2020-21 school year, and 42 of those students are Black or Hispanic. Black and Hispanic students that represent 49% of the district population, and make up 18% of the gifted classes. White and Asian students make up 43% of the district population, and 72% of gifted classes. Over the past four school years, those percentages have been relatively steady. This is not a uniquely Champaign problem.

From NBC News, in partnership with The Hechinger Report:

“Nearly 60 percent of students in gifted education are white, according to the most recent federal data, compared to 50 percent of public school enrollment overall. Black students, in contrast, made up 9 percent of students in gifted education, although they were 15 percent of the overall student population.

Many factors contribute to this disparity. Gifted education has racism in its roots: Lewis Terman, the psychologist who in the 1910s popularized the concept of “IQ” that became the foundation of gifted testing, was a eugenicist. And admissions for gifted programs tend to favor children with wealthy, educated parents, who are more likely to be white.

Though it took several decades for gifted education experts to raise concerns, they have been trying to diminish segregation for a generation. If it were easy, it would be done by now.”

In Unit 4, gifted classrooms have been placed in elementary schools with higher percentages of Black and Hispanic students relative to the rest of the district, and what has been created, essentially, is a hierarchy within schools. This is neither the fault of the children in the program nor their parents, yet it exists in stark relief, and is reflected in the comments of parents who voiced concerns about the change* (emphasis ours):

“Removing the gifted program also removes other children from this safe environment.”

“I fully support integration through athletics, music, cultural programming, etc., and other school activities. But when it comes to an enclosed learning environment integration will only serve to bring down the level of interest, of scholarship, and of a hunger to succeed.”

“With a vote to remove the gifted program you will be holding the excelling students of our community back. You will take away their safe learning environments in many of the schools.”

“Inevitably, the level sinks to the lowest common denominator, leaving the highest achieving students with little opportunity to reach their potential.”

This emphasis on safety is troubling, and implies only those who are high achieving students are worthy of a safe learning environment, and those who don’t qualify for the gifted program are the source of danger. There is also an implication that differentiation is not happening or not possible, that the curriculum is “dumbed down” and uninteresting, and that those in regular classrooms do not have the desire and motivation to learn. With an overrepresentation of Black and Brown students in those regular classrooms, such statements reflect a racial bias, whether conscious or not.

In June 2020, the Unit 4 school board adopted an anti-racism resolution, and making a commitment to address the effects of systemic racism evident in the schools:

“The district seeks to reduce the effects of structural/systemic racism, defined as ‘a system in which public policies, institutional practices, cultural representations, and other norms work in various ways to perpetuate racial group inequity.”

Self-contained gifted classrooms have perpetuated this inequity. While students may benefit from their participation in them, if that benefit perpetuates a system that is detrimental to others, then it must be reexamined. There is evidence that students identified as gifted do not necessarily make more significant academic gains in a homogeneous classroom as opposed to a heterogeneous one. Likewise, there is evidence that integrated classrooms is beneficial to the learning outcomes of all students.

Reexamining and reconfiguring does not necessarily mean elimination of services for students who are gifted and talented, and it shouldn’t. As one parent states:

“Gifted is an educational need. It is far different than the “smart” kids being apart from other students. Gifted students often require different structure and learning opportunities that are not available in traditional classrooms.”

Indeed, gifted students should receive educational supports that meet their needs. Some students who are labeled as gifted also meet the definition of “twice exceptional”, meaning they are high achieving, yet also have a disability that may interfere with their learning, such as learning disability, emotional or behavioral disorder, or autism spectrum disorder. Special education operates under the mandate of providing the least restrictive environment for students with disabilities and special needs, meaning all efforts should be made for those students to remain in the regular classroom with support, and separate learning environments should only be used if the severity of the disability and goals set in an Individualized Education Plan cannot be met in that manner.

Though it is not mandated through law, it makes sense to apply this manner of approaching education to students who are identified as gifted. As much as possible, students should be a part of the regular classroom, but with added support to accelerate their learning and provide the proper challenges where they are needed.

The National Association for Gifted Children identifies three primary strategies for meeting the needs of gifted students: acceleration, flexible ability grouping, and specialized pull-out programming (that doesn’t necessarily indicate separate classrooms). Regular classroom teachers in Unit 4, and in many districts, already employ flexible ability grouping, particularly for literacy. Acceleration is also an option in Unit 4 currently, which allows students to be placed “at the instructional level that best matches the student’s needs by allowing access to a curriculum that is usually reserved for children who are older or in higher grades.” This can be done through early entrance to kindergarten or first grade, moving up a full grade, or allowing a student to attend a higher grade level class for certain subjects (i.e. a 3rd grader who needs math acceleration does math with a 4th grade class). School districts in Urbana and Mahomet already utilize acceleration and classroom differentiation to challenge high achieving learners, without the presence of self-contained classrooms.

Change is difficult, and parents are hard-wired to fiercely advocate for their children, especially when it comes to their education. Those who are concerned about sufficient educational opportunities for their gifted learners should continue to hold the district accountable for meeting their needs. But this is a step in the right direction to create more equitable schools.

*Parent comments obtained through a FOIA request for emails sent to Unit 4 regarding the gifted program.

The Editorial Board is Jessica Hammie, Julie McClure, and Patrick Singer.