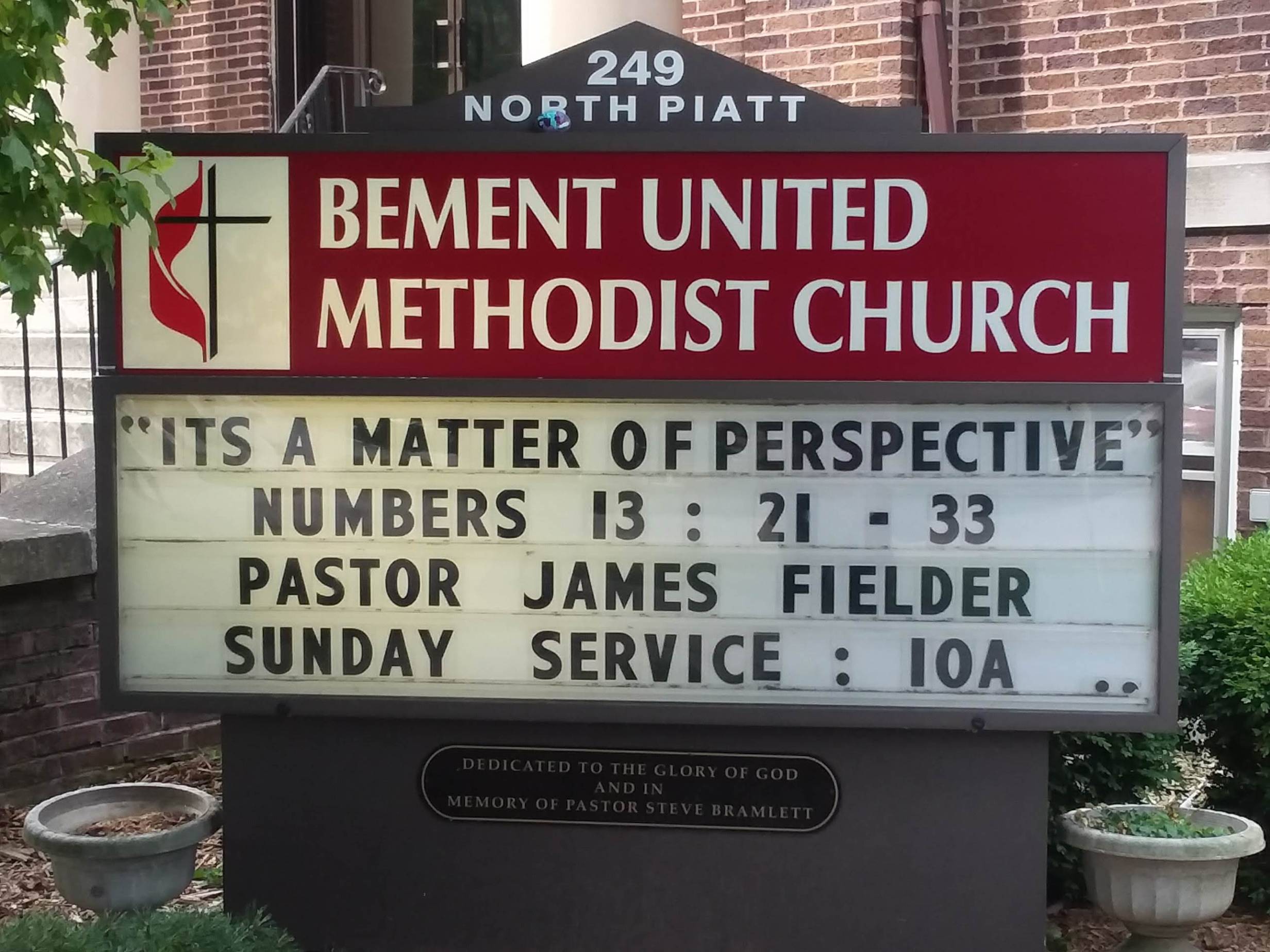

When I initially learned that my friend James (aka The Right Reverend Dr. James Fielder) accepted a call to pastor Bement United Methodist Church a little over a year ago, several in our nexus of friends were surprised, and honestly concerned for him.

“He did WHAT?”

“Where is that?”

“1800 residents? Are there any black folk there?”

See, whether traveling North, South, East or West in the United States, African Americans take our visits off the interstates and into rural America very seriously. So, deciding to live and work in one of these locales gives the individual and the extended family pause as we move into fervent prayer and soul-searching.

It takes little more than visiting Bryan Stevenson’s lynching memorial website to be reminded of how many small communities all over America, including in Central Illinois, were lynching sites for African Americans.

So, as I decided to interview Pastor Fielder for this series, I also had to look up Bement on Loewen’s sundown town website, just to be sure.

A 2017 article by Jack Shuler on sundown towns in the Midwest defines them as “towns where, black Americans knew, they were not welcome once the sun went down….In sundown towns across the Midwest, black Americans were denied housing, persecuted, or violently evicted during a period from the 1890s to the 1940s, leaving a homogeneity that has defined the towns for much of the past.”

Fortunately, Bement did not make Loewen’s list or Stevenson’s map. Bement was founded in 1854 by Massachusetts businessman Joseph Bodman. Bodman lobbied for Bement to become a stop on the Great Western Railroad in 1854. Bement was also a historic Illinois community because it was the town in which Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas planned and launched the Lincoln-Douglas debates.

On a Sunday morning, my family and I wound our way from Champaign through gorgeous corn fields for 37 minutes to make the 10 a.m. worship service at Bement United Methodist Church. Yet, we three adult passengers — including my mom who fled Jim Crow Mississippi in 1960 — journeyed cautiously with the full knowledge of the surveillance of African American travelers.

Upon arriving, we scrambled up the stairs and slinked gratefully into the back row during the “Call To Praise and Prayer” as my seven-year-old daughter flopped down in the seat, cranky and underwhelmed by the experience so far.

Service then unfolded with congregational greetings as members moved around hugging and shaking hands with fellow members and visitors alike. We then watched a great video previewing the upcoming national United Methodist Church initiative “Back To Church Sunday” on September 15th, that depicted diverse perspectives on the road back to regular church attendance. Bement United Methodist Church will celebrate their 161st Anniversary this year.

After the video, one of the members came back and asked if she could escort my daughter to children’s church. When she said “they have snacks,” my daughter shook off her reservations and bounded down the aisle to join the other children downstairs.

Pastor Fielder then prayed for various church members and lifted up a prayer about gun violence nationally:

“As a Marine, when I used an M-16 I knew I was going out to kill someone. I was trained to do that. So, for me, that weapon and weapons like it should not be used casually on our streets, public space and in our homes. I pray for wisdom from our leaders to devise sensible laws for gun control as I don’t want to have to fear going to the store, parks, movies etc…” The congregation responded with a booming “AYYYYYYYYY-MEN.”

The remainder of the service was rounded out with the sermon, closing hymns and prayers, and an invitation to “Holy Happy Hour” where we visited with Pastor Fielder and had refreshments and lovely conversations with members.

After filling her plate with snacks, my daughter whispered to me, “Mommy, I like it here. I don’t want to leave.”

I ended my day completely bewildered. There have been few spaces in my life that have been overwhelmingly white, yet genuinely warm and welcoming. So, I couldn’t wait to talk with Pastor Fielder about what exactly was happening at Bement United Methodist Church.

******

Smile Politely: Remind me again: How did you, an African American pastor from St. Louis, get assigned to the white, rural Bement United Methodist Church?

Reverend Dr. James Fielder: During my process of becoming a Methodist, I was recruited by the United Methodist Church to do “cross-cultural appointments” (ministering to congregations that were different from one’s own culture).

During the process of seeking an appointment, I prayed, “Lord, please hear me: I don’t want to go to a sundown town.” (I laughed: see I told y’all that sundown town history is REAL).

And yet, when I received the packet from the bishop, notifying me that I had been assigned to Bement, Illinois, I just said: “OK, God.” I was so ready to pastor that I said, “Wherever you send me I will go.” In addition to sending me to a completely white rural church, I didn’t realize when I accepted this call that the church was in decline and would probably be likely to close in three to five years.

And yet, when I received the packet from the bishop, notifying me that I had been assigned to Bement, Illinois I just said: “OK, God.” I was so ready to pastor that I said “Wherever you send me I will go.”

SP: How does this experience compare to your past ministry experiences?

Fielder: Well, clearly, there were some differences culturally as I transitioned from Baptist or Pentecostal to Methodist. You know, Methodists have the reputation of being very low-key and quiet. However, I used this opportunity to remind the congregation of the history of founders like Allen who were considered enthusiastic and energetic. It was our movement who partnered with the Pentecostals during the mid-1800s and shouted and prayed all night. So, I deploy our history as Methodists to usher in worship experiences like standing, call and response, clapping, etc,.

Another key element of my ministry is that I bring my whole self and I invite my friends and family and incorporate worship elements and music from my African American tradition.

SP: How has the church changed since your arrival?

Fielder: So, the first Sunday I preached there, I arrived at church early and made sure I hugged and greeted every member and asked about their week, their family, their concerns before the service starts, and now I do it every Sunday morning. The congregation said “If you change anything, don’t change that practice.”

Fundamentally, we just spend more time together. In the past, no one would stay for Holy Happy Hour. Now, folks stay after and eat and fellowship with one another. So we just hang out. We have movie nights and hang out. We do bible study and hang out. We went to a baseball game together and hung out. I meet with folks to hang out. I am working on an outdoor service so we can hang out some more.

So you ask me how the church has changed: they have always been really good folk. They just needed to be pastored. They needed a shepherd to love on them and care about them, and reach folks where they are.

But I have also called them to more diverse worship experiences and more intergenerational and youth worship. As a result of all these efforts, we have families returning and our BUMC community is thriving.

SP: What kind of work did you have to do to become comfortable with each other as a black pastor of a white congregation?

Fielder: My perspective first and foremost: I had to change my perspectives about them. There was a time when I would have walked into a space and seen folks in overalls and would have made certain assumptions about who those folks were.

But I think the key to being effective in ministry, even in pastoring a church where the congregation is different from you racially, is that you have to be comfortable in your own skin. I worked for Farm Credit for 20 years. How many black folks do you know in the agriculture spaces? I was also in IT. How many of us are there in information technology spaces?

I use my background and experiences as a minority in a lot of areas to get to know people. I firmly believe that you cannot pastor people if you don’t know them. So, I have a running breakfast every week in town. I am in the schools. I am at the funerals and graveside services whether they are members or not. I just got involved with the Fellowship of Christian Athletes here. I am visiting in the hospitals. I am doing home visits to get to know folks and give them a chance to know me.

I have just found it important just to love on folks, regardless of race.

Has it all been perfect? Of course not. There have been some challenging moments.

I officiate a grave-side funeral and three of the relatives of the deceased refused to shake my hand or greet me. And I said, “OK, well, I know who you are now”.

There was an occasion when I was driving back to the church and I looked up and saw the flashing light of the police. And you know my St. Louis/Ferguson background flared up and I began to pray and sing Negro Spirituals out here in these fields: “Ohhhhhh, Jesus, wontcha’ hear me and come by here!” I just pulled over, placed my hand on the dashboard and got ready. But amazingly, he was the nicest officer. He was kind and easy going and just gave me a warning. And as he pulled off, I was in a daze it was so uneventful.

On another occasion, I have had white people come to me and ask me “You are the pastor, where? The pastor there?! Are you, OK? You know, there are some real rednecks in this town.” And I say, yes, so far I’ve been fine.

However, I also let my congregation know that I have to seek out my support systems as well. I will invite visitors of color to worship with us. Also, I have to worship in African American spaces at times. I have to spend time with family, extended family, my fraternity brothers (Fielder is a member of Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity, an African American fraternity founded in 1911), other African American preachers to maintain my own self-care.

I have just found it important just to love on folks, regardless of race.

SP: So, what are we missing? What have we misunderstood about these communities?

Fielder: In homogenous communities where people do not have many opportunities to interact with people of different races, they just don’t do it very often, or have gotten out of the habit of doing it. So it takes work on their part…and it takes grace and patience on the part of people of color to work with them.

And that is where it is important for church leadership to train clergy and staff so they can create opportunities for all of us to keep growing and building bridges toward one another.

The pressing social issues here are not related to diversity. However, this is a community that has serious struggles with meth and heroin addiction, domestic violence, and gambling — especially video gambling addictions. So as a pastor, I have to walk with the community through these challenges.

There are also economic disparities. You have some folks who are very well off and some who are struggling to get by. In the past, our church used to give out money to community members up to four times a year. However, we are moving away from that practice to partner with local social service organizations to meet a broader set of needs for individuals in crisis.

SP: What advice would you offer other Central Illinois communities considering more diverse leadership (or diversifying their congregations) during these tense times nationally?

Fielder: I think it is really important to go into the community to serve the community, not just preach. Pastors and church leaders must be willing to be a presence in people’s lives and have contact with people. It is also important to assess your community and adjust to the community, not require the community to adjust to you. Finally, if you plan to work toward a multicultural church, you must be intentional, deliberate and gracious and seek to spread grace in all your interactions with others.

To learn more about Bement United Methodist Church, check out their website or Facebook page. You can read the first installment of When Faith Speaks here.