True confession: when I moved to Champaign three years ago, I lived practically within sight of the Cattle Bank on University and First and had no idea that it housed the Champaign County Historical Museum.

I eventually learned that the Cattle Bank is the oldest standing commercial building in Champaign and a historical landmark, but it took me another year or so to realize that the building is still in use: it’s home to a large collection of artifacts from roughly two centuries of Champaign County history.

In my defense, the Champaign Country Historical Museum isn’t exactly well marked. This sign, which faces First, is about eight inches across:

And the “open” sign, which faces the parking lot behind the museum, is pretty hard to pick out:

Even so, the museum is open every weekend. And its current collection numbers somewhere between ten and twenty THOUSAND artifacts.

The Champaign Country Historical Museum has been around for decades. After gaining 501c3 status in 1972, the museum acquired the Wilber Mansion on University. Sue Wood, the treasurer and co-president of the board of trustees, remembered that that space offered lots of small rooms for intimate displays of the museum’s items.

Hal Balbach and Sue Wood, co-presidents of the museum’s board of trustees.

But by 1998, the Wilber Mansion was falling into disrepair, and the Museum was struggling to maintain it with its small budget. The Museum sold the Wilber Mansion in 1998 to a private buyer and shortly thereafter moved into the Cattle Bank, which had been restored and added to the National Register of Historic Places some years prior thanks to the efforts of then-mayor of Champaign Joan Severns.

The story of the Cattle Bank captures much of the historical change that has taken place in central Illinois over the last 150 years. The bank, a branch of the Grand Prairie Bank, was built in 1857. Corn and soybeans hadn’t yet made their home here since the means for converting central Illinois’ wetland and prairie into arable land had yet to be developed. So, in Wood’s words, this was “cattle country” — and cattle barons made serious cash. In 1855, the Illinois Central Railroad was laid in Champaign, which made the city a hub for cattle shipping between Chicago, St. Louis, and other major cities. The Cattle Bank opened in Champaign in response to this flood of prosperity. Only a few years later, in 1861, one cattle baron imported cattle infected with hoof and mouth disease, and as a result of the outbreak, the cattle industry collapsed in central Illinois. The Cattle Bank was used as a grocery, an insurance store, a tobacco shop, and many other storefronts until it was renovated and combined with the neighboring Oakley building in the 1980s.

Unfortunately, the Cattle Bank is much smaller than the Museum’s previous location. According to Wood, there are five usable areas for display, which means that the Museum can only show a very small percentage of its collection. Hal Balbach, the other co-president of the board, estimated that only 1% of the Museum’s holdings are currently on display. The vast majority of the items in storage across the street, next to Dallas and Co.

The museum’s two permanent exhibits are a turn of the century grocery store and a military room, which primarily houses military paraphernalia from the Civil War, World War I, and World War II. A third room, dubbed the “Victorian Room,” has traditionally displayed late-nineteenth-century items. For the past couple years, however, it has been jam-packed with items that were displayed during the Champaign Sesquicentennial celebration; it’s basically impossible to walk into. Two other rooms — one featuring children’s items and one featuring a random assortment of twentieth-century items — were put together a few years back by students in an eighth grade class. Suffice it to say, the displays currently on view are in somewhat suspect shape, though the items themselves are fascinating.

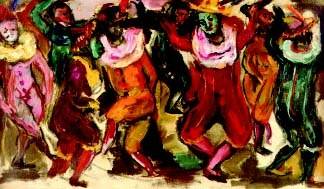

In the children’s room, there are several paintings by Louise Woodroofe, a local artist who traveled with and painted the Barnum and Bailey Circus in the summers from roughly the mid-1930s to the mid-1940s.

In the children’s room, there are several paintings by Louise Woodroofe, a local artist who traveled with and painted the Barnum and Bailey Circus in the summers from roughly the mid-1930s to the mid-1940s.

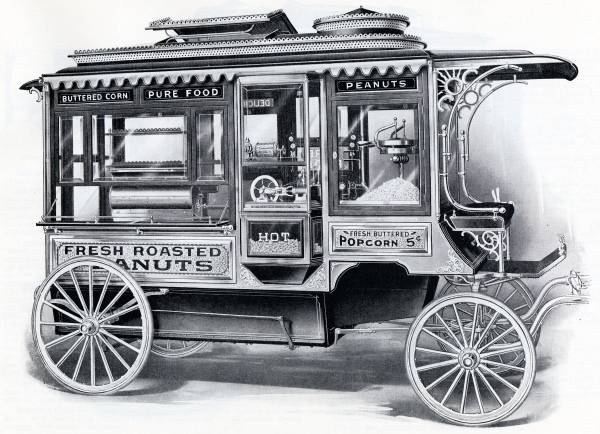

Balbach said that one of his favorite items is the museum’s 1919 popcorn machine, which is typically in storage but will come out for this year’s Fourth of July parade. He also mentioned a recently acquired surveyor’s compass dating from the 1840s, which was used to lay out many of the major towns and roads and roads in Champaign County.

The Museum’s quilts, many of which were over a hundred years old, were incredibly vibrant. The panels of this 1901 crazy quilt were sewn and signed by ten women who were members of a Ladies’ Aid Society.

This adding machine is well used: you can see worn areas in the metal from the number of hands that have touched it.

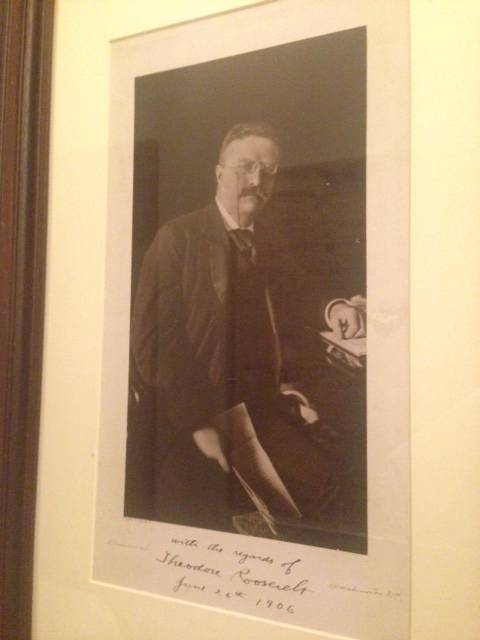

And then there’s this Teddy Roosevelt signature. He stumped in Champaign’s West Side Park in 1912.

I asked Wood and Balbach why it matters to preserve items from our local history. “If we don’t save these things,” said Balbach, “there won’t be anything to show people about what the past was like except for words and stories. We won’t have a sense of how people really lived.”

That seems true. I can tell you that in the Museum there is a display of paper shirt collars, a pre-refrigeration icebox, and a mourning wreath made from the hair of the dead, but I don’t think you’ll experience the distance of the past or the oddness of our present unless you go stand near those things yourself.

I left the Champaign Country Historical Museum feeling that despite the mild inconvenience of finding a time to visit (it’s only open ten hours a week), the ramshackled quality of its displays, and the difficulty of discovering that the Cattle Bank is a museum at all, this is one of the most important places in C-U. We should find ways to bring those thousands of items in storage into view. We should care about this place more.