Last March, I was startled to see a story in The News-Gazette about an athlete from Urbana whose name I hadn’t heard for years: Charles “Tyke” Peacock.

Last March, I was startled to see a story in The News-Gazette about an athlete from Urbana whose name I hadn’t heard for years: Charles “Tyke” Peacock.

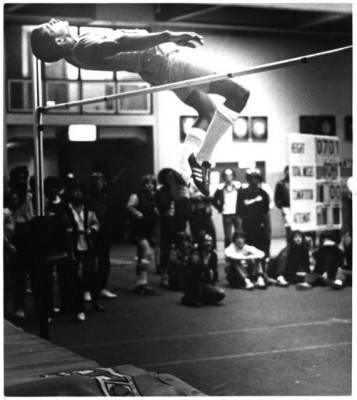

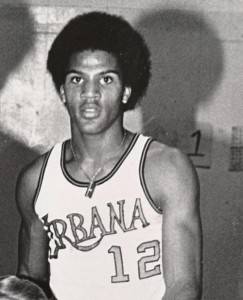

Peacock, who is now 50, was a track and basketball star at Urbana High during the 1970s. His athletic achievements were numerous after high school as well. To name a few: he competed on the track team at Modesto Junior College in 1980 and 81, played basketball at the University of Kansas during the 1982–3 season, and won the silver medal in the men’s high jump at the 1983 World Championships in Helsinki.

However, Peacock is also known for what he didn’t do, but was expected to: win the gold medal for the high jump at the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles.

Peacock started abusing crack cocaine in the early 1980s, and it was his drug use that caused him to not entirely live up to his athletic expectations. From the 1980s on, he stole things to get drugs, and did two extended stints in prison in the 1990s (he also worked different legitimate jobs during these years as well and served a year in the military, but would always get back into trouble as a result of drug use). He was still using in the fall of 2010 when he was picked up in Bakersfield, California on a theft charge and extradited back to Champaign County to face charges here.

In the fall of 2010, Peacock was sentenced to six years in prison by Judge Difanis for burglary. However, Difanis made the unusual decision of allowing him to stay out of jail for a few months before a hearing in March. Difanis did so in part because Peacock was already in the SAFE House live-in substance abuse recovery program run by Canaan Baptist Church in Urbana.

Peacock was eventually allowed to plead to a lesser charge and was sentenced by Difanis to probation, and — instead of going back to prison — Peacock went back to SAFE House to continue his recovery.

Peacock is currently married, and his wife lives in the Phoenix area. He has three biological children.

I spoke to him recently at SAFE House, where he’s been drug free for over eight months.

An athlete from Urbana

Peacock has warm memories of growing up in Urbana: “It was fun, especially coming from a big family. I’ve got four sisters — one just passed — I’ve got three sisters remaining and two brothers, so it was interesting to say the least, but fun. I come from a real close-knit family.”

Peacock has warm memories of growing up in Urbana: “It was fun, especially coming from a big family. I’ve got four sisters — one just passed — I’ve got three sisters remaining and two brothers, so it was interesting to say the least, but fun. I come from a real close-knit family.”

After graduating Urbana High School in 1979, he headed west to Modesto, California for Junior College. From there, he went to The University of Kansas on a basketball scholarship. Although Peacock was one of the top high jumpers in the world during the early 1980s — his personal best is 2.33 meters — his first love was basketball, and his dream was to one day make it to the NBA.

Peacock did fairly well during his season playing basketball for Kansas, but said his style of play wasn’t always a good fit for the era:

I was ahead of my time. By that, I mean I was that flashy kind of player you see more now, and when I came up they weren’t partial to that. The coaches had more control, without question. You’ve got some tremendous athletes now — that’s not to say we didn’t have them then — but I think that’s because of how the game has changed. They allow a lot more wide open playing now. A lot more freedom. Back in my day we called them ‘playground players.’ But whenever you had one of those playground players, they considered them too flashy for going outside of the offense. And that was kind of my style of play.

Unfortunately, Peacock was doing more at Kansas than playing basketball, and his abuse of a new drug on the scene caught up with him later in a really bad way. He recalled:

I first started using crack cocaine — which was my drug of choice — when I got to Kansas in 1982, although I had tried snorting it when I was in Modesto. It was my first time smoking it. It was called freebasing then, and it’s a ton more addicting. That’s when it really first hit the scene. I had seen heroin users when I was coming up, just around town, and I saw what heroin had done to those people, and that made me run from that. But I had never seen a person who was on crack or who was freebasing at the time, and what it had done to them.

So I didn’t have a clue. Of course I knew that I wasn’t supposed to be doing it. I have an addictive personality — if I do something, I like to do it all the way. It took me places that I never thought I’d go. It made me do things I never thought I’d do. It led to my troubles with the law, because when I ran out of money my first solution was to take something that didn’t belong to me.

When I think now with a clean head — I can’t believe it was me. I wasn’t raised like that. Early in my addiction, I remember my mom asking me where she had gone wrong, but she didn’t. I was grown and I made my own decisions — they were just bad ones.

For the 1983–84 academic year, Peacock transferred to Fresno State, seeking a better fit with their basketball program than at Kansas. There was a Sports Illustrated story written about this period of his career, profiling where he was at as both a high jumper and a basketball player. Peacock sat out from the basketball team at Fresno State for one year, and then dropped out of the university completely in the fall of 1984, feeling that things weren’t working at the preseason basketball drills.

Peacock’s NBA dreams never panned out, but he came close. He was invited to tryouts for the Houston Rockets, but said he couldn’t participate fully in them because of a scheduled track meet: “This was back in 1983. At that time, I had the World Championships in Helsinki, so it put me back in Houston like three or four days after the tryouts, so I pretty much just worked out with them rather than tried out.”

He was invited to try out again next year, but he didn’t. By that time, he was more into his addiction, and was also worried about drug testing during a time that the NBA was especially concerned with recreational drug use. “That was right after the whole thing with Len Bias,” he said.

As a high jumper, though, he was at his peak during the early 80s, winning medals at international meets and competing side by side with United States track and field athletes on their way to becoming household names: “That was my era. To me, people like Carl Lewis weren’t celebrities, because we all traveled together as the U.S. team: Carl Lewis, Evelyn Ashford, Edwin Moses, Greg Foster. These are really big names in the track and field world, but they were my teammates.”

Likable and personable, Peacock had a good public image during this time and an endorsement deal with Puma, the athletic gear company. Footage of him high jumping appeared in the video for The Pointer Sisters song “Jump (For My Love).” On the surface, things looked really, really good: he was a popular athlete doing great things, on his way to doing even greater things.

Structure

These days, Peacock isn’t able to work out as much as in the past. When I asked him what he was doing this summer to stay in shape, he replied:

Not much. I had a knee surgery about two years ago, I tore my Patellar Tendon, and I’m just now to the point where I’m walking without a limp. So, I haven’t been doing a whole lot on it. When I get a chance, I ride a bike. Now here I am scheduled for another knee surgery. It’s all the wear and tear over the years catching up. I think it’s a direct result of just my athletic career.

While he may not be working out at the gym, Peacock’s, days in the SAFE House program in Urbana keep him plenty active:

We do a lot of work. Canaan Church owns a lot of the structures on this particular street. They own this house, obviously, the apartment complex next door, the house across the street and a few houses down the block. So we maintain those properties. Yesterday, I was up on a roof all day, re-roofing.

We have prayer at 6:30 in the morning and devotion at 7:00. Devotion lasts an hour. We do whatever chores we have around the house, and then we do whatever work is scheduled for that day.

His evenings are also carefully scheduled:

Monday nights we have a meeting at Urban Restoration over on Bradley; we have an in-house meeting Tuesday evening; Wednesday nights we have Bible Study down at the church; Thursday we have choir rehearsal because we’re required to be in the choir; Friday nights we get a break — it’s a free night going into the weekend — and we get up on Saturdays and have a men’s class. Then we go out SWATTING. SWAT stands for Soul Winning Action Team. We go around and talk about the goodness of God — try and save some souls. Sunday, we go to church, and afterward we watch movies, maybe hang out. That’s pretty much the week at SAFE House.

Peacock sees the highly structured setting of SAFE House — where he’s been since last fall — as key to his recovery:

I credit the SAFE House. The SAFE House structure is why I’ve been clean eight months, and that’s a blessing in itself. Now, I had tried different rehab settings before, but they were 28-day programs or 30-day programs. Well, you know, as long as I was using, that was just resting time. I needed something with some longevity. Now I have consistency. And we do so much … we stay so busy, that you really don’t have time to think about using these drugs.

I have found that it’s exactly what I needed in my life, because I had been so far away for so long from structure that it’s ridiculous. It’s been so long since I finished anything I started. Once drugs consume you, you don’t get things done — you might start in on something but you’re not going to finish it. So that’s my motivating factor, that’s my driving force. Just to finish. I tell you, I’m eight months in and time has flown. It doesn’t seem like I’ve been here that long. Four more months and I’m done.

However, the challenge of staying clean after leaving the structured setting of SAFE House (it’s a year-long program) back into mainstream society is still ahead of him:

Brother Green with SAFE House says, ‘You’re not done. You’re just done with the SAFE House.’ But I look forward to the day I graduate, because as they say around here — that’s when the rubber hits the road. That’s the true test. Although we’re not mandated to be here now — you can leave out that door at any time — you don’t want to. It’s a little bit different when you’re on the outside. I know that and I realize that.

I know that I’ve been delivered from drugs, but there are other areas of my life that I’m working on. Because just because you’re cleaned up from drugs doesn’t mean that you’re not going to have any more problems. It doesn’t mean that there aren’t other areas in your life that are out of whack. You tear down and hurt a lot of people when you use drugs for as long as I did.

The 1984 Olympics

Leading up to the 1984 Summer Olympics, Peacock was fully expected to win the gold medal for the high jump. On paper, there was every reason to believe this would happen — it’s easier to predict the high jump based on past performances than other types of athletic events. Peacock told me:

I feel with my entire being that I would have won the gold medal that year because I had competed against everybody in the world who was somebody in that event and beat them. You can determine from how high people are jumping what’s going to happen, pretty much. In 1981 and 1983, I was ranked the number one high jumper in the world. So 1983 I was very hot; I was almost unbeatable. And so when I went into the ’84 Olympic trials I was chosen to win the gold medal in the high jump.

Not many people knew he was using crack: “I’m sure they weren’t suspecting me. The press liked me back then — I’ve always been a people person, always, a likable guy, fairly intelligent — no one thought. No one thought. And I tried to keep it that way.”

While he might have been able to keep his secret from other people, he knew he couldn’t beat a drug test, so he found a way out:

I was in so much shame from what I was doing, and that’s why I faked the injury, because I didn’t want to be found out. But although it was only two years into my addiction, it had consumed me. I was no longer doing the drugs, the drugs were doing me. And so I faked an injury because I knew they were going to drug test me.

Peacock said he sees now that he could have gotten help for his addiction at the time, and possibly salvaged the situation, but didn’t realize that then: “I didn’t recognize that I had an addiction — I looked at it as I had let something get a little out of hand and I didn’t want people to know about it.”

Even after the 1984 Olympic Games had come and gone, the regret from letting the gold medal get away from him caused his drug use to get even worse: “I believe that my throwing away the Olympic Games really did lead to me going off the deep end. Because that’s when I really started partying. Because I thought, ‘What have I done?’ I truly think that was the thing that kept me high for so many years.”

Today, Peacock believes that if he had actually won the gold medal, it would have led to his death:

I let not winning the medal bother me for a lot of years. But I see now that God doesn’t make any mistakes. And if I had somehow slipped through the drug test and all that … I had a contract with the Puma shoe company at that time, and it was in my contract that if I won an Olympic gold medal I got a million dollars. And I am not confused about this now one bit. The way I was then in my addiction, I would have flat out killed myself if I had a million dollars.

I was a likable enough guy — the press liked me — to where I would have had a lot of other endorsements, which would have brought more money.

Peacock didn’t talk about faking an injury or carrying the burden of his failed opportunity for a gold medal for years, but when he finally did, it brought an unexpected sense of relief:

And it wasn’t until recently that I told anyone that. And I’ll tell you what, when I did, I’ve never felt so free in my entire life. Because carrying around that kind of thing for so many years? Oh my goodness, can you imagine what it must have been doing to me? It felt like a tremendous weight had been lifted off of me.

And I’ll tell you what blew me away, is that it was not like I thought. I thought people would say, ‘Man, what a loser,’ and ‘How could he have done that?’

It was completely the opposite. People actually opened their arms and embraced me for having the courage to tell the true story. I don’t think anyone likes rejection, but it needed to be said.

Crime, punishment, and recovery

Peacock has done extended time in Illinois prisons on two occasions: once in 1994 and again between 1998 and 2000. He’s mainly been in trouble for stealing in one form or another. When I asked him if his offenses ever went beyond property crimes, he replied:

No, that was pretty much it. I would get high, run out of money, and the first thing I’d do is steal something I knew I could sell or trade for some drugs. And I had even gotten into taking people’s personal stuff. Like credit cards. As a matter of fact, when I came to the SAFE House, that’s what it was for. Just things like that. And you know, I’ve never taken anything from anybody if I wasn’t high or trying to get high.

I was thinking about that once I came to the SAFE House — that’s a true statement: I’ve never taken anything if I wasn’t high. The young lady whose credit card I took before I came in here didn’t have a lot of money. All she was doing was trying to take care of her family. It hurts my soul to think now that she was out there struggling and here I am taking from her. Or for anyone, for that matter, that they were working hard for something and I stole it. That’s no way to live — just to blatantly take. And I have a true sense of remorse for it now, but you’re not thinking about any of that when you’re consumed by drugs. It’s just about, ‘Get me another one. Get me another one.’ Every crime I committed I was either on drugs or trying to get them — drugs always had something to do with it.

Peacock has made many attempts at staying off drugs in the past, and said he was successful during his times in prison:

You can get anything you want in prison, if that’s your choice. But fortunately for myself, I was able to stay off drugs when I was in. That is such a controlled environment that you know you’re taking a very serious risk when you’re in there. If you get busted all that’s going to do is add more time. So I just chose to stay away from it completely.

However, on the outside, he wasn’t able to stay clean. He said of his many failed attempts:

I was really trying to stay away from it, but I think I failed because I was always trying to quit for the wrong reasons. I did it because I knew my mom wanted me to quit. I did it because I knew my children didn’t like it — although they didn’t know exactly what Dad was doing, they knew something wasn’t right. Or I did it because it was ruining my relationship with my wife, but it was never for Tyke. It was never because I was tired of using. But this time it was for me. I was sick and tired of being sick and tired. I truly was.

And I never implemented God into the recovery, but now I see it has to go hand in hand. Because God created us. And do you think he created me to go down and do that? No, absolutely not. And that is why I do give all praise and glory to God for how I am today. We do have a forgiving God. If you look at it from a human standpoint, there are a lot of reasons for people not to forgive me. You hear people say that and you think that they’re holy rollers or that they’re Bible thumpers, but that’s not what I consider myself. I just know I’ve been blessed.

When Peacock was extradited from California back to Illinois last fall, he fully expected to be going back to an Illinois prison for a long time:

When I got in this last trouble for stealing that girl’s credit card, they put me under the extended term, under Class X sentencing, because I had done this same type of thing so many times over. My sentence carried six to thirty years. That scared the devil out of me. Just hearing that scared me to death. So I agreed to a sentencing deal, where they capped it at twelve years. So now I was looking at six to twelve years, which is still an awful lot. But I had come to terms and accepted it. I had done wrong, so I was comfortable with whatever I had coming to me. You know, ‘Buddy, you wanted to play, now it’s time to pay.’

So he was shocked when Judge Difanis told him he was letting him stay out jail for the holidays and to come back in March:

But when I went to court for my sentencing, the judge told me he saw I had started making the right steps. I had only been here at SAFE House like a week and a half, but he saw that I was a least trying to get something in place to make changes in my life. So he told me, ‘Since I can see that you’re trying here, I have no problem sentencing you to the bottom end of what your sentence carries: six years in the Department of Corrections.’ But then he said, ‘I’m going to do something that I’ve never done; I’m going to let you stay out for the Holidays.’ So he did that, and I didn’t have to come back until March 23rd.

Peacock speculated on the Judge’s motivation, and expressed gratitude for the decision, especially given that it allowed him to be near his family in Champaign-Urbana when his sister was terminally ill:

Judge Difanis, I’ve had him before, and he has sentenced me before. But, I think by me making some steps in the right direction, he wanted to give me a chance. So he let me stay out for four months, and during that time frame my sister had been diagnosed with cancer — the oldest of all of us kids. She was like a little mom to me. She ended up passing in December.

Still, he thought he’d be going back to prison in the spring:

My surrender date was March 23rd. Before I went in, I told the guys here at the SAFE House, ‘OK, guys, it’s been nice,’ because I thought I wasn’t coming back. I got there, and they allowed me to withdraw my guilty plea for the six year sentence, and plead to a lesser charge, something that was probational, because my initial charge was not probational. I know that was God showing me: I am real, and this is what I can do. This is what I can do if you follow me. I think that was orchestrated from the very beginning through God. I believe that wholeheartedly.

Because it was twice that people over there said, ‘This is the first time; this has never been done.’ When I hear stuff like that, I can’t be confused about who is in charge.

What about the victims?

In any story of rehabilitation and recovery, eventually this question comes up: What about the victims?

Peacock is a likable guy; he was the best high jumper in the world in 1983, and he’s one of the greatest athletes ever to come from Urbana, but all of that might not mean so much to someone he’s stolen from in the past. In the comments section of the March 20, 2011 News-Gazette article “Urbana’s Peacock awaits decision by judge” (an article that brought back the name Tyke Peacock to a lot of people living in C-U in the 70s and 80s, including me), a commenter wrote:

The News Gazette reporter Jenn Kloc did not do her job when it came to researching this man prior to publishing this news story. The readers deserve the whole story, not just a story about a supposedly great man finding God and getting off drugs. Why were the felony warrants in Arizona not mentioned in this story?

This guy is a predator that needs to be taken off the streets. I doubt Arizona will spend the money to extradite him back for the felony warrants he is facing there that he decided to not appear on. I’m glad he found God and the Holy Spirit, but he may be using religion as a means to escape incarceration. People like him make me happy we have the 2nd Amendment Right.

The commenter also provided hyperlinks to the Arizona warrants.

I mentioned the comment to Peacock and asked him about his current legal situation in Arizona. He replied:

When I got probation, the probation department here in Illinois asks where you lived before and so forth, and they run checks, so that’s how they found out about Arizona. And what Phoenix told them is that, ‘We’re not looking to extradite.’ So pretty much what they’re saying is, ‘Leave us alone, and we’ll leave you alone.’ So that’s exactly what I’m going to do. And in my opinion, that’s another blessing. Because I wasn’t convicted of any of that stuff that I was charged with, and I think that’s why they’re probably not looking to extradite me. So long as I stay away from them, I don’t think they’re too concerned about coming to pick me up.

I also asked Peacock what he’d say if he could talk to that particular commenter in the Gazette. How would he respond to being described as a predator? What would he say to anyone, for that matter, who felt that he was getting preferential treatment in the form of probation now for being a star athlete years ago. He responded:

I believe everyone deserves a second chance, and I realize I’ve had a second and third and the whole bit. But, I’ve paid my debt to society also. What I would say to that person is just to concentrate on what’s going on with me now and to see my actions from this point forward. Because if I get into some more of that kind of living, then those comments would be correct — that I’m a predator and this and that.

But there has just been a drastic overall change in the way I think about things. The best way for me to defend myself is to just do what’s right. As long as I do what’s right, that person can’t badmouth me anymore on what I’m presently doing; they can badmouth me on what I’ve done in the past, and rightly so, but it is exactly that — the past.

A leap of faith

When Peacock leaves SAFE House at the end of his year — assuming he makes it — he’ll probably have less of a problem finding work than many ex-offenders with felony convictions on their record. He’s been able to find coaching and other types of jobs in the past, even with his record. All the same, his background has been a problem in job searches before. Peacock said he wants to be honest about his past when looking for work after SAFE House:

I’ve had trouble finding work in the past, but what I will not do is lie. And I don’t care what position it is. I will not lie about it. And if people feel like they’re taking a chance, then they have that right not to hire me. But I don’t want to come in lying, get the position, and then have it come up later down the road and have to get fired because of it. That’s not practicing what I’m preaching; I don’t want to live like that anymore.

But what kind of work does he see himself doing in the future? “My passion is working with kids. Man, if I could get a job at a YMCA or at a boys or girls club — and I’ve been offered to work with a new track team that’s starting around town — I’d be blessed. Because God knows my heart.”

But what kind of work does he see himself doing in the future? “My passion is working with kids. Man, if I could get a job at a YMCA or at a boys or girls club — and I’ve been offered to work with a new track team that’s starting around town — I’d be blessed. Because God knows my heart.”

Thanks to Stacie Armstrong for her help with this article.

~~*~~

Photo credits:

Photo above by Renee Jackson Peacock. Used with permission.

Feature image from CU-CitizenAccess.

Black-and-white photos from the Morning Courier.

Color image from Peacock’s Facebook page.

I feel with my entire being that I would have won the gold medal that year because I had competed against everybody in the world who was somebody in that event and beat them. You can determine from how high people are jumping what’s going to happen, pretty much. In 1981 and 1983, I was ranked the number one high jumper in the world. So 1983 I was very hot; I was almost unbeatable. And so when I went into the ’84 Olympic trials I was chosen to win the gold medal in the high jump.

I feel with my entire being that I would have won the gold medal that year because I had competed against everybody in the world who was somebody in that event and beat them. You can determine from how high people are jumping what’s going to happen, pretty much. In 1981 and 1983, I was ranked the number one high jumper in the world. So 1983 I was very hot; I was almost unbeatable. And so when I went into the ’84 Olympic trials I was chosen to win the gold medal in the high jump.