We continue our conversation with Professor Bob McChesney, author of the new book The Death and Life of American Journalism: The Media Revolution that Will Begin the World Again (Part I of the interview can be found here). You need only utter the words “newspaper” or “journalism” and Prof. McChesney will open a vein, so let’s get right to it.

RH: What do you say to the idea that capitalism simply gives the people what they want? I mean, to me it seems like it gives people the bare minimum of what they’d be willing to accept. Where is the market failure in delivering a product that people actually do want?

BM: Well, it’s a complex question and it’s difficult to give a simple answer. We have to distinguish here between the market giving people what they want in industries like hamburgers or hot dogs or even motion pictures and the market giving people what they want in the case of journalism. If we look specifically at journalism, our argument is that the market always had a very difficult relationship with journalism historically. We chronicle that relationship in the book.

The best way to understand journalism as an economic undertaking is not as a private good, not as a good that conventional capitalists compete with each other to produce, and they try to successfully respond to audience demand and whoever gives the people what they want gets the richest. That’s sort of the myth of how competitive markets work. And that doesn’t really help us understand journalism because in journalism it doesn’t really work as a private good. It’s much better to think of journalism as a public good, something like national defense or public education or basic academic research. This is something that a society requires, a free society and a healthy society desperately requires. And a market, left to its own devices, will not work. It will fail. It will not produce sufficient quantity or quality. And consumers can’t use the market to express their desires and engage as citizens. It simply doesn’t work. And that’s what we have to understand about journalism.

The best way to understand journalism as an economic undertaking is not as a private good, not as a good that conventional capitalists compete with each other to produce, and they try to successfully respond to audience demand and whoever gives the people what they want gets the richest. That’s sort of the myth of how competitive markets work. And that doesn’t really help us understand journalism because in journalism it doesn’t really work as a private good. It’s much better to think of journalism as a public good, something like national defense or public education or basic academic research. This is something that a society requires, a free society and a healthy society desperately requires. And a market, left to its own devices, will not work. It will fail. It will not produce sufficient quantity or quality. And consumers can’t use the market to express their desires and engage as citizens. It simply doesn’t work. And that’s what we have to understand about journalism.

Journalism, with the exception of that brief period when advertising opportunistically supported us, has always been a public good. It has always existed as a result of massive public subsidies. But for the market, it would never have been anywhere near satisfactory in American history, except during that brief era of advertising-generated journalism. And if we understand it as a public good, then it’s easier to see how it’s very hard for individuals to express their desire for journalism in the marketplace, what they want as citizens. All the research we’ve done shows that, for people, it’s very important to have journalism. They’re willing to support it even if they themselves don’t necessarily plan to consume it directly. The market doesn’t always reflect how people feel about journalism. And I’ll give you an example of what I mean.

I will never go to a National Park again in my life. Ever. I’ve been to them. I like them. They’re great. I’m glad they’re there. But I’m 57 years old. I’m not going to be around that much longer, and when I’ve got free time, there’s other stuff I’d rather do with my time. Now, by market analysis, what that would lead people to believe is that I think we should just get rid of National Parks. Pave them over. Sell them off. Since I’m not personally planning to go there, I don’t want them. I’m voting with my feet in the marketplace. Hell No to National Parks! Just lower my taxes. Get rid of those goddamn things out there and lower my taxes right now.

But in fact, I really want to see National Parks expanded. I’m willing to pay more taxes to have more National Parks. I’m all for National Parks even though I’m never going to go to one. Because I know it isn’t just about me and what I consume. It’s not about what goes in one end and out the other. That’s not the be all and end all of human existence, of social existence. And as a result of that, I’m willing to pay more to have National Parks even though I’m never going to go to one. I know my children might. I know people I don’t even know will go and enjoy them. I know that ultimately my brothers and sisters of my species, thousands of years down the road will hopefully enjoy them. It’s a lot bigger than just me.

Well, journalism is the exact same thing. Journalism is something that, even if someone doesn’t plan to read a newspaper or a news website, it’s important to everyone to know that someone is monitoring the government. Someone is monitoring city hall. Otherwise the whole system of governance collapses. Someone’s gotta have an eye on these corporations screwing people over, and on health care, and the banks. And even if you’re not going to consider journalism as imperative, there’s someone doing that.

Well, journalism is the exact same thing. Journalism is something that, even if someone doesn’t plan to read a newspaper or a news website, it’s important to everyone to know that someone is monitoring the government. Someone is monitoring city hall. Otherwise the whole system of governance collapses. Someone’s gotta have an eye on these corporations screwing people over, and on health care, and the banks. And even if you’re not going to consider journalism as imperative, there’s someone doing that.

It’s just like even if you don’t have school-age children, you understand it’s imperative we have a literate society. That that will definitely affect you even if you don’t have kids who go to school. And that’s how we have to understand journalism. If understood that way, the notion of the market just doesn’t really apply to it. It’s not an effective way to understand it. Because our research shows the same people who can watch the Jerry Springer Show and Jackass can also say, “I’m willing to support my money going to pay for journalism because I’d like to know what the heck people in power are doing. And I want someone to have their eyes on them.”

RH: One of the analogies and arguments that I like is journalism as public good, as part of the public sphere, as infrastructure really. I think in terms of both making the case to the public as well as implementing, I like the idea that you build the housing or delivery system but you don’t dictate the content, similar to the way you build the interstates but people drive whichever cars they want. Could you speak a bit about your proposal as such?

BM: If you understand journalism as a public good, if you understand that the commercial market for journalism has collapsed and disintegrated and it’s not going to return — if you accept those two points and I think the evidence is pretty strong for both of them — then you’ve got to ask the obvious question: How did the United States have such magnificent journalism for the first 100 years of American history before advertising played much of a role in newspaper economics?  And the answer we provide in the book, which I think is astonishing to most people, is that we had extraordinarily massive public subsidies, government subsidies that created and spawned a very rich, diverse news media. These are primarily postal and print subsidies; we spell them out in great detail in the book. We have to return to that sort of thinking if we’re going to have journalism today.

And the answer we provide in the book, which I think is astonishing to most people, is that we had extraordinarily massive public subsidies, government subsidies that created and spawned a very rich, diverse news media. These are primarily postal and print subsidies; we spell them out in great detail in the book. We have to return to that sort of thinking if we’re going to have journalism today.

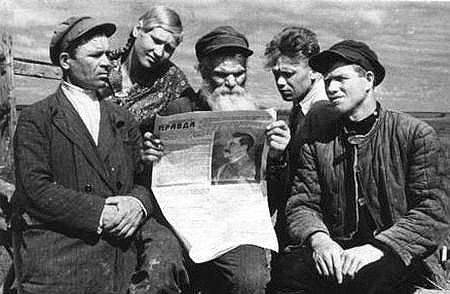

We need to have very large, significant public subsidies but at the same time we have to be very careful not to let government have control over the nature of the content produced by that money. Government interference with news content is not acceptable. On this point, a lot of Americans, I’d say most Americans are instantly skeptical. “That’s impossible,” they say. He who pays the piper calls the tune. They’re going to influence the content. They’re going to use their leverage over the funding to warp who gets the money. The cronies of government benefit. And the journalists who are critical of government will not only not get money, but eventually they might get locked up, roughed up, tortured or murdered. It’s not too difficult for many people who are critical of the idea of government subsidies to say we’re talking about going to something like Stalin and Pravda or Pol Pot’s Cambodia. And I think it’s really imperative to take that very seriously. Because I agree. If there is any sense that a government subsidies to journalism are going to lead to government control over journalism content, I would oppose them. John Nichols, my co-author, has been a working journalist for newspapers for 27 years and managed newsrooms for many of those years.

What we do is actually look at all the other major democratic nations in Northern Europe and East Asia, like Japan and Britain, and Switzerland and Austria, and Germany and the Netherlands and Belgium, and Denmark and Finland and Norway and Sweden. And in all those countries, what we discovered is that they have enormous subsidies for public media and even for journalism. If the United States paid the same per capita rate, in terms of journalism subsidies or public media subsidies, the national government would have to spend between 20 billion and 35 billion dollars annually. By way of comparison, the federal government today spends roughly 400 million dollars on public broadcasting and community broadcasting. So, they all spend vastly greater sums than we do. And what’s striking then is, you say, “Well gee, are those countries totalitarian hellholes?” “Are they reminiscent of Stalin’s Russia with Pravda being the party paper? Do they have death camps and are they shooting people and murdering a quarter of their population like Pol Pot in Cambodia?”

We did a lot of research on that and what we discovered is not only are those countries still very much free societies, but as a rule, the vast majority of them are rated, even by conservative, pro-business publications like The Economist magazine, as being more democratic than the United States. Countries with the largest journalism and public media subsidies are ranked as the most democratic nations in the world, according to The Economist. Moreover, according to Freedom House, a group which largely examines government censorship of private news media — Freedom House rates all the countries in the world and it argues that the freest, most uncensored private commercial news media in the world are in the same countries that also have the very largest press and public media subsidies.

So the evidence is pretty clear, in virtually all other major democracies that are comparable to us economically, that you can have massive public media subsidies, journalism subsidies, and have a vibrant democracy, a free press and a completely uncensored private, commercial news media that’s more robust than our private, commercial news media. So that’s the evidence we use to get us to this point. But let’s talk about what we do then.

Once we grasp that we can have a grown-up conversation about how we do this and get away from the mud-slinging and name-calling without any evidence behind it, then we think there’s basically two stages of issues here. The first one is we’ve got to do something immediately to fix this crisis. We don’t have the luxury of appointing a commission and waiting thirty years. The way we have to respond to the disintegration of journalism right now is the same way we would respond if our nation were under foreign military attack. If our borders were under attack and bombers were hovering over our cities dropping bombs, we would not appoint a commission and say, “Guys, come back in five or ten years and tell us whether or not we can defend ourselves.” That would be preposterous. We would say we better defend ourselves. We need all hands on deck. Do whatever it takes to make sure we remain free and then we’ll deal with everything else after we’ve defended ourselves. We need to approach the collapse of journalism with something like that sort of urgency.

In the near term, right away, we need to increase spending for public and community media tenfold, from 400 million to 4 billion, with nearly all that money earmarked to go to the local stations, public and community, college and university, for the hiring of journalists to cover their communities.  There are lots of out of work journalists who need work; let’s get them to work. Secondly, we’re about to lose an entire generation of young people who want to do journalism. It’s the worst labor market for journalists ever. I mean, the 1930s looks like a golden age for hiring compared to today. We need to have a Write for America similar to Teach for America or some branch of Americorps to put 10,000 to 20,000 young people to work doing journalism across the country, covering underserved communities.

There are lots of out of work journalists who need work; let’s get them to work. Secondly, we’re about to lose an entire generation of young people who want to do journalism. It’s the worst labor market for journalists ever. I mean, the 1930s looks like a golden age for hiring compared to today. We need to have a Write for America similar to Teach for America or some branch of Americorps to put 10,000 to 20,000 young people to work doing journalism across the country, covering underserved communities.

Third, we’ve got to immediately have money to transition dying daily newspapers into digital post-corporate newspapers with local owners, non-profit owners, foundation owners, worker owners. We’re open-minded to any number of alternatives of how to do it, but we’ve got to come up with something better or we’re going to have our newspapers continue to shrink until they disappear. I don’t think we can afford to lose the idea of having newsrooms accountable for covering an entire community. Newsrooms that try to, not just segregate communities into bite size chunks for advertisers, but regard the entire community as fair game for news and as their responsibility so a person in a community can learn about other people in the community who aren’t in their exact same demographic group by reading the news. So that’s the sort of stuff we have to do immediately

Then in the long run we’ve got to come up with ways to really have large subsidies for journalism for the digital future that understand the public good nature of journalism on one hand, and also embrace digital technologies. In the book we go through several; I’ll mention one now. The one I’ll mention comes from the economist Dean Baker. (ed. Baker has a great article on the myth of free market fundamentalism at Counterpunch today. Also check out some of his many interviews on youtube. Good stuff.) Dean Baker argues that if you give every American a $200 voucher, they can donate to any non-profit or non-commercial medium of their choice. The only condition would be that whatever the media produced happens to be, it would go in the public domain and be made free for anyone online immediately. So the public subsidy would produce something everyone in the public has access to for free.

It would be a massive public subsidy of news media, non-profit, non-commercial news media. And there would be no government control of who gets the money. Any news media that meets basic criteria to prevent fraud would be eligible. And there would be no government monitoring whatsoever of the editorial content. So it’s a massive public subsidy but one without government control of content. It allows for innovation, experimentation, and entrepreneurial approaches. And it develops direct links between readers, citizens, and their news media without the intermediary of advertisers or commercial owners. So, I think that’s the sort of direction we need to go. There are other ideas that people have that may be better. We offer these suggestions not as a final word on the subject, but to begin a necessary discussion about how to save journalism.

Ed. Many thanks to Prof. McChesney for taking the time to speak with me. I’m hoping to have one final conversation with him, so if anyone has any particular questions they’d like to ask, please make note in the comments.