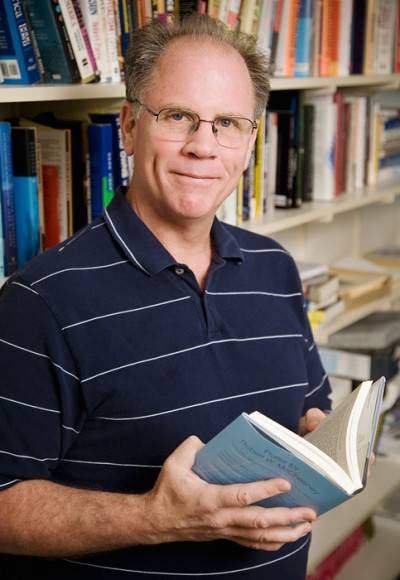

Bob McChesney has spent some time thinking about the media. A professor of Communications at the U of I, host of Media Matters on WILL 580 AM (a superb program with guests such as Amy Goodman or this Sunday’s Joseph Stiglitz), and a journalist in his own right, McChesney might have some idea of what he’s talking about. No great surprise, Dr. McChesney has surveyed the current landscape of journalism and found the results…unsatisfactory. Terrifying, in fact. The press is in a dire situation. And that means you are too.

By now, documenting the collapse of journalism is old hat, but McChesney (along with his co-author John Nichols) is offering a path out of the wilderness, a chance to create a press greater and more vibrant than this country has seen in a long time, maybe ever. His book, The Death and Life of American Journalism, is as important and compelling a work as you can find yourself in the good fortune of encountering.

There are two presuppositions in the book: One — that journalism (the collection and distribution of information) is essential for a healthy, successful democracy. Two — that journalism is in a state of profound crisis. It hardly requires a high degree of familiarity with the anemic media to find those premises to be self-evident. So the question remains: what do we do about the threat to democracy, self-governance, and liberty? At a time when threats to freedom are being discovered under every government action and public dollar, it’s almost refreshing to encounter one that I’m sure exists.

Even if you absolutely disagree with McChesney and Nichol’s recommendations, this is the reasoned argument you must respond to. If you care about democracy, if you care about information, if you care about the society you live in, you need to think about what’s just around the corner. This is a good place to start.

Without further ado, I give you Dr. Robert McChesney.

RH: Why not let journalism as we’ve known it die? Why not let market forces and the internet do what they will to journalism?

BM: Those are two different questions in a way. The first one — why not let journalism die? I don’t have any problem with much of what we know as journalism dying. The second question though — why not let market forces and technology do what they will with journalism, and if they can develop a new and better journalism great, and if they can’t, well, we’ll say we gave this democracy thing a shot for a couple hundred years and now we’re throwing in the towel.

As for the second question, my whole book is an argument that our freedoms, our quality of life, and our system of governance is predicated on having a credible, quality independent journalism, and the market and technology will not give us that. The evidence is now in. I think if someone says we don’t care, that’s a legitimate argument, but you’re saying you don’t care if we don’t have a credible system of constitutional government with liberties and freedoms because that’s what goes out the window when you stop having journalism.

RH: And you don’t believe that we will be able to rely on internet-driven journalism?

BM: It’s not really an opinion. It’s an empirical question. The question is, we’ve had the internet now for a couple decades. We’ve had the world wide web for eighteen years. We’ve seen the collapse of commercial journalism for three decades. We’ve had plenty of time now to look and see exactly how much journalism is being generated online. And the evidence is in. The case is closed. It’s not even in question anymore.

The internet is barely generating any paid journalism at all. After 15 years of people throwing tons of money into it, there’s hardly anything to show for it. There’s no one that thinks it’s going to get any better at this point except those trying to hustle and con people out of money for their investments or get grants. Unless someone’s trying to run some P.T. Barnum number on people, for anyone that’s looking at it objectively, the facts are clear. We’re not going to have paid journalism on the internet in anything more than a smidgen of what we need.

And the reason for that isn’t hard to figure out. This isn’t really metaphysics that we’re talking about. The reason is very simple. Commercial journalism in the United States has been commercially successful and lucrative for the past 100 or 125 years primarily for a single reason – 60 to 100 percent of the revenues that supported it came from advertising. Advertising always had an opportunistic relationship to journalism. It didn’t support journalism because it had any intrinsic interest in newspapers or radio or tv news. It did it because it had no other way of accomplishing its commercial aims. As journalism goes to the internet, advertisers no longer have any connection to journalism whatsoever. They can support news websites if they want but they’ve also got 10,000 other options that are every bit as valid commercially, and increasingly advertisers are finding other places to go. An entire pool of money that used to provide 60 to 100 percent of the revenues is in the process of dramatically shrinking. Newspapers have already lost all classified advertising — 20 billion dollars in the last decade. It isn’t coming back.

And so there’s no way you can blame the entrepreneurs of America for being morons because they can’t make money doing journalism on the web. What money there is might be sufficient for a small number of websites, a handful of paid jobs, but not to support an industry with thousands of independent competing newsrooms and 100,000 or 200,000 paid journalists. That’s just not going to happen. And again that’s not an opinion, it’s an empirical question and no one is giving any credible argument whatsoever that they can squeeze blood out of that rock.

RH: In the book you discuss how this crisis was on the horizon long before the internet, brought about by corporate conglomeration and downsizing — that this crisis was visible at least as early as the ’70s. Could you help me understand some of the underlying structural causes for the decline as separate from advertising revenue moving to the internet?

BM: The argument that we make in the book is that the people who simply blame the internet for the collapse of commercial journalism and the current crisis are not giving a complete and accurate picture because that argument suggests two things. One, that journalism, until three or four years ago, was doing fantastic, just hitting the ball over the fence, just absolutely had it made, just glory days until along came Google and Yahoo, which is preposterous.

The problem is, our journalism, in terms of news rooms, in terms of the number of working journalists per hundred thousand citizens, has been in decline for decades. And the reason people haven’t noticed until the last few years, except for scholars, has been that these companies that have gobbled up all our news media in the last three decades were making so much profit that people assume that with any company making money, then everything must be going great. No one really lifted up the hood to see what was actually going on, to see the tremendous commercial pressures being put on journalism and the gutting of newsrooms.

So the real crisis in our view is that the marriage of commerce and the public service of journalism was always a problematic relationship. And it worked for better or for worse for much of the 20th century when advertising was there, but even at its best it had serious problems. But now, thanks to corporate concentration and conglomeration and commercial pressures, the marriage of commerce and the public service of journalism has completely disintegrated. Commerce has won and journalism is dead.

The internet accentuated that process and made it permanent, made it irreversible. The internet, even if our journalism was in fantastic shape, was going to bring about a complete reconstruction of journalism eventually. But the way it’s taking place in the United States owes a lot to the crisis of journalism that was developing long before the world wide web, and it’s why calls to simply return to the market system, like all we have to do is have a rich guy run all our media and gobble it up and they’ll do a great job of adjusting their status quo old media system to the internet is preposterous. Those guys did a crappy job running our old news media. They ran it into the  ground. This is an opportunity to get rid of them. They’re walking out the door. They’re getting out of journalism. We should be glad to see them go. Take a hike Rupert Murdoch.

ground. This is an opportunity to get rid of them. They’re walking out the door. They’re getting out of journalism. We should be glad to see them go. Take a hike Rupert Murdoch.

RH: I saw that this week, he instituted his $2 per month paywall for the Times, so apparently he’s still clinging to the idea that people are going to pay for content on the internet.

BM: Well I don’t blame Rupert Murdoch. If I were a capitalist or I were Rupert Murdoch, or I was with some news media corporation, I would absolutely be experimenting with paywalls. I would be doing everything in my power to make money out of journalism. The problem that Rupert Murdoch has is that it probably won’t work. A paywall system might work for a handful of elite media that appeal to the upper class. But for general news, it’s absolutely not going to happen. We’re not going to see a paywall system generate sufficient revenues to support the equivalent of major daily newspapers in every city in the united states. There’s no reason to think that at all.

Part II next week…