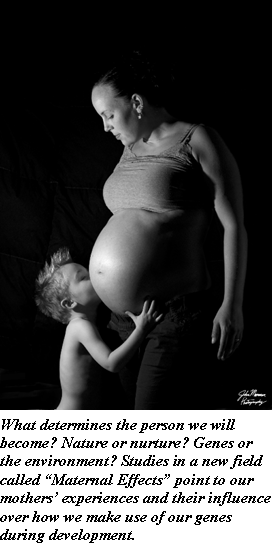

Long before we’re born, our mothers’ experiences with certain situations and substances can affect the kind of person we will become. Now, we’re starting to find out how this happens.

Long before we’re born, our mothers’ experiences with certain situations and substances can affect the kind of person we will become. Now, we’re starting to find out how this happens.

It isn’t surprising to hear that attacks by a big scary predator can cause stress in an animal. Grizzly bears and great white sharks still tend to bring about this response in our species. But it might be surprising to hear that attacks by predators in previous generations can change the response in the current generation. That grizzly bear that was sniffing around the tent on your parents’ last Colorado camping trip before you were born probably scared them silly. It might have been so scary that your mom and dad still sleep in the car years later for fear that another bear might wander by. Recent research suggests, quite surprisingly, that your parents’ experience with that grizzly could also be affecting the way you respond to bears, even if you never heard their terrifying story. A popular example published in 2010 in the journal The American Naturalist showed that exposing pregnant crickets to a big, predatory wolf spider changed the behavior of her cricket babies after they hatched and grew into adults. Somehow, it primed the babies so that they could recognize the smell of the wolf spider and react before it was too late. When the spider showed up, fangs at the ready, these crickets survived better than if their mothers hadn’t been attacked.

Cool, right? I think so. That’s why I’ve chosen maternal effects as the focus of my PhD research. It is a phenomenon that everyone who was ever born can relate to — and that’s everyone. Most often it happens when a mother that is pregnant, or full of eggs if she doesn’t give birth to live young, experiences something that affects her babies later in life. That “something” the mother experiences can be just about anything, from stressful situations to exposure to toxins to what she eats. You may have read that bisphenol A (BPA), a chemical compound used in the manufacture of plastics, is currently under investigation by the FDA for its potential to cause birth defects during development. The FDA’s concern is that BPA is everywhere, and has been accumulating in the environment and in our bodies for the better part of a century. In the last decade or so, we’ve started to see it interfering with the endocrine system (the body’s system that regulates hormones) in mothers and their developing fetuses. A person or animal exposed to BPA through their mother’s diet is more likely to develop problems with the reproductive tract, including cancer, and experience permanent changes in the brain, behavior, and the immune system.

Do scary encounters with grizzly bears leave tiny, microscopic bears on your DNA that can be passed down to your kids? Most scientists agree that no, they most certainly do not. Image credits: Bear; DNA.

Understanding how permanent changes result from exposure of mothers to these “somethings,” including BPA, is obviously important. That’s why it’s a primary focus of biological research in the U.S., and that’s why it’s the focus of my own research. To study maternal effects, I use the three-spined stickleback, a fish species that for a long time has been a model animal on which to study the link between genes and behavior. But we’ll get back to genes later. To stress the stickleback mothers, I chase them with a predator fish, the northern pike. The pike is to a stickleback what a charging, hungry grizzly bear is to us: a big, scary predator. Once the stickleback moms lay their eggs and they’re fertilized, I raise the babies to adulthood and expose them to the same big scary pike. What have I seen? Sticklebacks have a different stress response if their moms were exposed to the pike.

Somehow, fish moms can warn their babies just like cricket moms can. But maternal effects on stress aren’t restricted to crickets and fish. And maternal effects can sometimes lead to negative outcomes for the babies, as we see with prenatal exposure to BPA. Research on reptiles, amphibians, and mammals has confirmed that a mother’s experiences can influence how her babies deal with stress throughout their life, often in unexpected ways. It often causes babies to have the wrong reactions and, in some circumstances, causes them to grow smaller or develop birth defects. We know maternal effects that are either good or bad for the offspring (what scientists refer to as “adaptive” and “maladaptive,” respectively) both happen, and they happen in species across the animal kingdom. But, importantly, we don’t know yet exactly how they happen.

Can female stickleback fish warn their babies about the presence of toothy predators, prodding scientists, or photographers that love extreme close-ups? Image credit.

Can female stickleback fish warn their babies about the presence of toothy predators, prodding scientists, or photographers that love extreme close-ups? Image credit.

In some studies, it has looked like hormones pass from a mom to her developing embryos and affect them that way. But embryos, especially early embryos, don’t have an endocrine system. They can’t make or respond to hormones until later in development. So how can hormones from a mom change anything in her embryos? The trick seems to lie in the intricate turning on and turning off of genes known to biologists as “gene expression.” More exactly, we think hormones are somehow changing the expression of genes that normally happens during an embryo’s development. For example, recent studies in rats carried out at Columbia University show that there are certain sensitive periods during early development when gene expression can be changed by the developing embryo’s environment. When a rat mother experiences a stressful event, some genes in her embryos are turned on when they normally would be turned off, others turned off when they normally would be turned on. Without changing which genes are passed on from a rat mother to her rat pups, somehow exposing a mother to stress changes how and when genes are used in her offspring. The result is a departure from the normal path of development: rat pups that grow into adults with brains and bodies that react differently to stressful events.

This might make it sound like we have maternal effects mostly figured out already. We don’t. It might also lead one to believe that we know most of the genes involved, whether and when they are usually turned on or off, and how they all interact to forewarn a baby that its mother saw an enormous crazy-eyed grizzly. Wrong again. Our knowledge of maternal effects on gene expression is based on a handful of genes in a handful of species. We don’t even have an understanding yet of how many genes in a single species are affected by a mom’s stress.

Famous nineteenth-century French scientist Louis Pasteur stares into a glass apparatus, totally unaware that his life might have turned out quite differently had his mother been attacked by a bloodthirsty grizzly bear. Image credit.

Knowing the number and type of genes involved in even one species would give us a great leg up in understanding maternal effects in general. If we knew how the genes involved are controlled, we could even possibly prevent or reverse diseases and other consequences of maternal effects that we see hurting the health of humans and the environment, like the effects of BPA. My goal is to describe this process in the stickleback. Figuring out how maternal stress affects gene expression in developing stickleback embryos will tell us a lot about how it happens in people and other animals. If all goes well, I will find a list of genes that will tell us more clearly how the experiences of a mother affects her babies. This will finally give us the chance to look closely at all of these genes, and will let us delve even deeper into the strange world of maternal effects.

But of course remember that the “something” a mother is exposed to need not be stress from a predator. Research has shown that a mother’s exposure to different diets, toxins, even different social situations can affect her offspring. After all, the sight or sound of a grizzly bear sniffing around your parents’ tent probably isn’t the only stressful event that could have affected you. Your parents might also have seen a scary movie about bears, invested in the bear market, witnessed a loss by the Chicago Bears (stressful if they were fans at the time), or might have been startled by people dressed as bears for Halloween. If they happen to have astraphobia, the pathological fear of stars, your parents might be afraid of the constellations Great Bear and Little Bear. It also might be possible that your parents were trampled by a pack of very big furry dogs that sort-of looked like bears. There is, of course, the outside chance that your parents experienced something stressful that didn’t involve bears. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

Written by Brett C. Mommer, M.S., PhD candidate in the Department of Animal Biology at the University of Illinois

Feature photo by John Mommer. Used with permission.

~~*~~

Smile Politely is proud to introduce a new running series we are calling “Science Politely” that will feature the work of graduate students at the University of Illinois throughout November and December. Working in collaboration with the students in a graduate course in Integrative Biology, Science Politely is a collaboration aimed at bridging the gap between town and university, between scientist and citizen, and between research and culture.