Attending college in the United States should be a time to be curious and expose yourself to new people, subjects, and ideas. But what if, from the top down, collegiate institutions are choosing which ideas, thoughts, and beliefs are acceptable?

This is the question the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC), it’s faculty, staff, and students, as well as the community of Champaign-Urbana, were faced with last year after the announcement of Dr. Steven Salaita’s termination following a series of tweets criticizing the Israeli government.

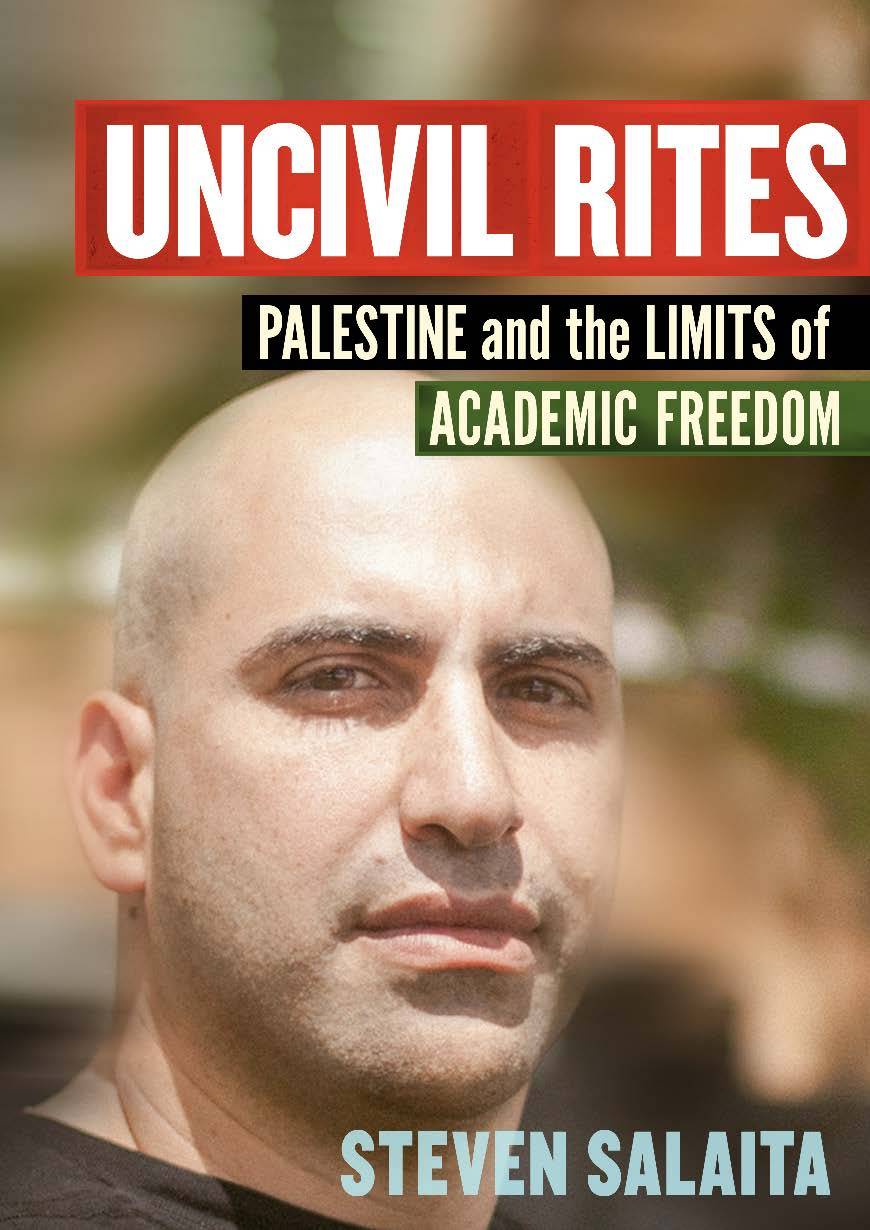

On Tuesday, October 13th, Salaita will be returning to the UIUC to discuss his new book, Uncivil Rites: Palestine and the Limits of Academic Freedom. This event takes place between 7-9 p.m. at the Independent Media Center in Urbana. The book explores issues of free speech, academic freedom and social justice activism and is directly influenced by his experience at the UIUC.

On Tuesday, October 13th, Salaita will be returning to the UIUC to discuss his new book, Uncivil Rites: Palestine and the Limits of Academic Freedom. This event takes place between 7-9 p.m. at the Independent Media Center in Urbana. The book explores issues of free speech, academic freedom and social justice activism and is directly influenced by his experience at the UIUC.

Whether you support Israel or Palestine, Salaita’s firing is problematic. U.S. colleges and universities are bastions of intellectualism, thought, and teaching, but if someone is making the decision that students should only be learning about certain ideas, or taking classes taught by professors with certain ideas, then they are prohibiting students from taking advantage of all there is to offer during their academic careers. Only the students themselves should be responsible for selling themselves short academically. Unfortunately, according to Muhammad Yousuf, the President of Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP) UIUC, “our current standards of academic freedom and the concept of ‘civility’ and other forms of respectability politics actually limit speech, especially from those in the margins.”

The first important term when discussing this issue is academic freedom, concisely defined by as, “the ability to discuss important issues without fear of censorship or termination.”

Perhaps the language of Salaita’s tweets was abrasive and offensive, but sharing and conversing about differing ideas and opinions is precisely how we learn and progress as humans. “If we limit what can be said about the Palestinian narrative, we’re not only oppressing Palestinians further, we’re also doing an injustice to students by limiting their ability to think beyond what they’re told and to think beyond the status quo,” said Yousuf when I asked him about the impact of limits on speech and academic freedom have on higher education instruction. “As long as professors do not let their views or the opposing views of their students influence their classroom performance, then that speech should be protected and encouraged,” Yousuf argued.

Moving on to our second vocabulary term, political consciousness is the ability to understand various social, political, and economic issues. Political consciousness cannot be achieved, unless we listen to “the voices on the margins.” Those differing and alternate perspectives that are easy to shun or close our ears to are important to developing and understanding our own opinions. Being aware of yourself, as well as the plight and experience of others, is what makes us human. To only offer one perspective is a huge disservice.

With an issue like the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, there is no one side and no one solution. This way of thinking only exacerbates the problem. This is because of our third term: intersectionality or “the idea that different forms of oppression interest, interact, and inform each other,” and as such, “class, race, gender, sexuality, ability, and other identity groupings inform how people are disadvantaged by the state or social institutions.” Essentially the experience of an upper-class black woman will be different from the experience of an Asian man in poverty because of the different identity groups in which they both exist.

Intersectionality is a term that Yousuf believes is important because, “To homogenize all Jewish people as being pro-Israel or Zionist is itself a form of anti-Semitism because it removes and marginalizes those Jews who are anti-/post-Zionist, or who simply do not support Israel. I think Islamophobic, anti-Arab, and anti-Semitic sentiments are present on all sides of this conflict and recognizing and fighting all of those is inherent to achieve justice in Palestine.” And this is important for any issue, not just Israel-Palestine. Directly related to this, Yousuf says he tries “fit all social and political problems I see into broader frameworks which tie them together, which both enables groups to form coalitions and to fight injustices in tandem.”

Even the three terms I have written about in this article cannot be fully understood separately from one another. Academic freedom means being able to share differing perspectives and ideas without fear of persecution. Academic freedom aids in the development of a more politically conscious society by exposing individuals to divergent, and often controversial opinions. Listening to and understanding those opinions allows you to see multiple sides of an issue and how an event or problem is not just the product of one thing. Because to think that the problems we see around the world and in society today are the result of one person, thing, or idea is naïve. And because there was no one cause, there is no one solution.

Furthermore, when we do not allow ideas in higher education to flourish, not only to we limit the amount there is to be gained by attending a U.S. college or university, but we also hinder our efforts to use ideas to make the world a better place for those who are disadvantaged.

As Yousuf said, “limiting academic freedom to only allow those who fit the status quo or norm to speak, as what happened in the Salaita affair, blocks off the critical analysis of discourse and systematic formations which is necessary to social justice projects. There’s also a connection between academics and social justice, in that we have to use academic theories, practices, and analyses to understand the basis for our social justice projects.” Therefore, when we only see value in certain theories in practices, we can only create social justice “solutions” aimed at one part of a problem, or solutions that help some, while continuing to hurt others. Social justice advocacy is rooted in the idea that if a system is broken, it needs to be fixed, Yousuf told me. But if the the place where we get those social justice solutions is a part of that same broken system, it seems we have a long way to go. We, as humans, are not at the height of progress.

“I’m not of the opinion that it is right to tell people what to think, but rather try to engage them to change their minds,” Yousuf said. And even if this article, attending the event, or reading Salaita’s book doesn’t change your mind about Israel-Palestine, academic freedom, or anything at all, at least you exposed yourself to something else and took the time to try and understand another perspective. Because even if you don’t change your mind, understanding another side’s argument in any debate, is beneficial when supporting your own opinion.

If you would like to hear more about academic freedom, political consciousness, intersectionality, and the other issues described in this article, you can attend the book event for Uncivil Rites: Palestine and the Limits of Academic Freedom, this Tuesday, October 13th at the Independent Media Center from 7-9pm. This event is sponsored by the Campus Faculty Association.

To learn more about Israel-Palestine and SJP-UIUC be sure to check out this Prezi. If you have any questions about SJP-UIUC, who they are, and what they do, you can direct them to sjp.uiuc@gmail.com.

Photos courtesy of Dr. Steven Salaita, Haymarket Books, and SJP-UIUC.