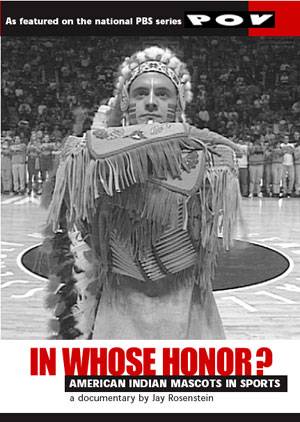

Imagine this: your film is presented as part of this year’s Super Bowl week activities in Phoenix. Then it’s added to the website of legendary journalist and PBS icon Bill Moyers. For many filmmakers, that could easily be the pinnacle of their careers. But for local documentary filmmaker and University of Illinois Media & Cinema Studies professor Jay Rosenstein, it’s just the latest chapter in the continuing saga of his 18-year-old groundbreaking film about American Indian sports mascots, “In Whose Honor?”.

Now considered the seminal work on the subject, “In Whose Honor?” is easily the most successful and widely seen film ever to come out of the Champaign-Urbana, Illinois area and the University of Illinois. Beginning with its 1997 debut broadcast on the PBS documentary showcase P.O.V., which was watched by an estimated audience of 1.1 million viewers, “In Whose Honor?” has been a mainstay at screenings, festivals, and in classrooms for nearly two decades. Yet this year saw a sudden spike of interest in the film due to the flurry of protests against the Washington NFL team’s name over the course of the football season.

I recently interviewed Rosenstein about the ongoing success of the powerful little film that just keeps going and going.

Melissa Mitchell: Let’s start with this: what is your standard boilerplate summary of what “In Whose Honor?” is about? How do you describe it to someone who’s never heard of it before?

Jay Rosenstein: “In Whose Honor?” is about the controversy over the use of American Indian mascots and nicknames in sports. That’s my one-sentence description.

Mitchell: Of course, people have heard of it… you passed along an anecdote that speaks to just how di rigeur “In Whose Honor?” has become as an educational tool. I’m thinking of the youngish person who said, yeah, yeah, yeah… I know about “In Whose Honor?”. We watched it in high school.

Rosenstein: That one came from Professor Robert Warrior, head of American Indian Studies at the University of Illinois. He told me he was going to show the film in one of his American Indian Studies courses, and the students basically said “not again, we’ve been watching that movie since high school!”

When I visited Hunter College in New York in December, I went to Kelly Anderson’s documentary history class. She introduced me to the class as a documentary filmmaker, and some of the students asked what I had done. And she said, “did any of you take the course ‘Representations of Race in Media’ and see a film called “In Whose Honor?”? And immediately half of them said “Oh yeah, you made that?” And then they gave me an ovation. That course at Hunter College shows the film every semester.

People constantly tell me about having seen the film in some class at some point in their lives. In fact, just today a visiting faculty member who I didn’t know stopped me in the hall, introduced herself, and then told me she shows the film in her classes all the time. That kind of thing happens to me over and over. It’s very cool.

Mitchell: So, what motivated you to tell this story — which centers on Charlene Teter’s story, of course —in the first place?

Rosenstein: I was at the University of Illinois, Urbana as an undergrad, and I was a huge sports fan — had season tickets to U of I football and basketball. Saw the Chief many times, but never gave it any thought one-way or another. It was just like the band and the flag girls to me, something to take up time waiting for the game to resume. Then sometime in 1989, and for reasons I can’t remember — maybe I was just there for lunch — Charlene Teters and a couple of other Native American students & staff were giving a talk at the Y about their experiences here at the university. And I was shocked by what Charlene had to say about how insulting the Chief was. At that moment I suddenly flashed on the thought that, “yeah, come to think of it, I’ve never heard an actual Indian say anything about their feelings on it before.” A little while later I was looking at the Daily Illini, the student newspaper, and I saw one of those cartoon caricatures of an American Indian in the paper, and it immediately reminded me of the cartoons I had seen of Jews that the Nazis had drawn — and then it all made total sense to me. Later I heard Charlene give another talk and thought, “more people really need to hear what she has to say.” So I thought if I made a film about it, many more people could hear her than she could ever reach in person.

Mitchell: When and where was “In Whose Honor?” first broadcast?

Rosenstein: PBS national series P.O.V., on July 15th, 1997.

Mitchell: Has it had other national broadcasts since then?

Rosenstein: Nothing else of that magnitude. They told me the audience for the initial broadcast was 1.1 million, based on ratings. Then each station had the rights to show it three more times in the next three years. I never got any data about that, but I know it was shown again in several places, because I would get some emails from people saying they just saw it on TV. It was also broadcast on the Worldlink channel in 2002, which was a PBS-run cable or satellite channel, which has now morphed into the World Channel, which is one of those extra PBS digital cable channels. It was also broadcast on Free Speech TV that same year, which was a small indie cable channel. Internationally it was broadcast on the Maori Channel of New Zealand in 2004.

Mitchell: I’m guessing the most typical venues for screening through the years have been festivals, educational and community events, classrooms, the whole gamut — from the heartland where this story originated to the nation’s capital, and all points in between. Am I leaving anything out, in terms of common venues/uses?

Rosenstein: Well, film festivals usually only program new work, so when you have a new film you usually do a “festival run” upon its release, and then it never really plays festivals again. That’s just the way the business is.

The most interesting or unusual screenings were that it was part of the “Video Native American Traveling Festival”, which had screenings throughout Mexico (they did the Spanish captions; never saw them), and it was shown at the Sami Film Festival in Kautokedno, Norway. Go figure. Those last two happened several years after the film had already been out — at least three or four years later.

But, while the whole film wasn’t shown on all these outlets, it did have segments broadcast on many prominent national programs, including: HBO “Real Sports with Bryant Gumbel”, PBS “NewsHour with Jim Lehrer”, ESPN “Outside the Lines”, and Nickelodeon “Nick News”. Also, on the ABC “World News Tonight with Peter Jennings.” After the film had aired on PBS, someone from ABC saw it, and they made Charlene Teters their “Person of the Week” and included a bunch of my footage — which I foolishly gave them for free.

I would say over the past decade it has been almost exclusively classrooms big and small, until this year, when all these public screenings started popping up on my Google Alerts.

Mitchell: Any international screenings? Or has the interest been in this country only? Obviously, it’s a U.S.-centric topic, but I’m thinking there could be sports teams in say, Canada, that use Canadian Indian names… or indigenous people in other countries that have been “honored” in similar ways. Or maybe not? Conquering countries and oppressing the vanquished is certainly not unique in world history, but naming sports teams for them, then pretending… creating this mythical narrative that in so doing we are “honoring” the oppressed population, might THIS be unique?

Rosenstein: The oppression and stealing of the land of indigenous peoples is pretty much the same story everywhere in the world, but yes, the naming of sports teams is uniquely American. Again, the film was broadcast in New Zealand on the Maori Network because the Maori are the indigenous people, and there has been consistent interest in Canada; it played at two Canadian Film Festivals — one in Vancouver and one in Montreal — and has been purchased by many Canadian Universities over the years. I couldn’t get it on Canadian TV though; they prefer Canadian made content.

Mitchell: Of course, the reason the topic has remained relevant since 1997 is because there are still high schools, colleges and pro teams throughout the land with American Indian mascots. And the ideological struggles and drama between enlightened vs. unenlightened members of the various continues to play out in these places, making your doc viable and in demand. Just curious: did that ever occur to you as you were making it? That there were so many mascots out there that “In Whose Honor?” would have a long shelf life as result?

Rosenstein: Absolutely. I was completely aware of the national scope of American Indian mascots and the same type of controversy that was playing out at the U of I was happening in other places. It was very much part of the research that I did at the time. Plus the fact that there had been a short period of time in the early 70s where this had been a high profile issue and some schools changed (Stanford & Dartmouth for instance) and I included that historical stuff in the movie. So I was aware of the potential of the film to be of interest in other places, and in fact, very intentionally wrote it so it would speak to the broadest and most common issues and not be hyper-focused on the University of Illinois. That’s why the second act of the film — where Charlene leaves the University of Illinois and goes national — is such a hugely important part of the film. At that point the story broadens out to include much of the nation: Washington R-skins, Atlanta Braves, Kansas City Chiefs, Florida State Seminoles, and it becomes no longer a film about Illinois, but more universally about American Indian mascots in all their forms, finally culminating at the Super Bowl in Minneapolis in 1992. So again, that was all done very intentionally.

As for the long shelf life, I can only say: never, ever, ever, even in my wildest dreams. The fact that eighteen years after its release, I still get emails about it, it still sells consistently to educational markets, and I still get Google alerts about screenings (Google wasn’t even close to being born when I made the film!), is too far beyond anything I could have imagined. It took every bit of extra time, energy, and effort just to put one foot in front of the other and finish it that I didn’t have the capacity to think about anything beyond that. Keep in mind — I didn’t make this film as part of a job, nor was I paid to make it. I was working a full-time job and did this film in my spare time. In fact, that’s how I’ve made all my films. I’ve always had a full-time job and made films outside of work (although being a university professor now allows me to work on my films in the summer and still get paid a salary).

Mitchell: Any idea what the average shelf life of a social-issue documentary is?

Rosenstein: No, but most social issues either evolve or change, so the films can quickly lose their relevance. For example, a friend made a great film about “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell”. But then, boom, it’s gone, and the film is done. And most films this age can get dated very quickly, so even if the information is still relevant, the film often just “feels old.” I’m lucky that despite being made with analog tape, “In Whose Honor?” still looks reasonably contemporary. I think once we move fully into 4K High Definition, it will then start to look old.

Mitchell: Can you name a few classic docs that have become just that… part of the canon that remain continuously in circulation, in history classes, or wherever?

Rosenstein: Harlan County USA, Tongues Untied, Salesman, Gimme Shelter, Grey Gardens, Titicut Follies, High School, Roger and Me, Thin Blue Line, Ken Burns’ Civil War, Man With a Movie Camera — those all come to mind as canon documentaries that you’d generally get agreement about. Probably a few more I’m not thinking of.

Mitchell: Time will tell, but… how would that make you feel if “In Whose Honor?” ended up in that company?

Rosenstein: Well, it will never be in that company for other reasons, but it already shows signs of having the same kind of longevity. Those “canon” films are part of the canon because they represent something significant in the evolution and history of the art and form of the documentary. “In Whose Honor?” is not in that category. I intentionally made it in a very mainstream kind of style, because I thought the information alone would be a little unsettling, and I didn’t want to add to that feeling by making the style of the film unsettling as well. I wanted the medicine to go down easy, so to speak.

But as a social issue film having continuing significance due to its subject matter and message — not style or form — it has become that kind of canon film. Film students don’t study it as a work of film, but every class in America about American Indian issues, contemporary Native Americans, Sports in Society, Race and Representation in Media, Race and Higher Ed., and a bunch of areas of Anthropology, Sociology, Education has been studying it for eighteen years and counting.

Mitchell: So, back to the doc itself… over the span of years since you made “In Whose Honor?”, have the screenings remained consistent? Was there ever a drop-off or lag time when interest waned?

Rosenstein: It’s the classroom use and the educational sales that have remained remarkably consistent over the past fifteen years (the first couple of years, sales were just extraordinary). Educational sales are the one and only thing I have actual data on, and it’s been in the top 10-15 sellers in New Day Films, my distributor, every year for its entire life, and that’s out of over 200 films, and keep in mind that the newest films usually have the most sales and then die down at different rates. People in New Day ask me all the time how I do it. I don’t know. I guess I just made a good film, the issue has remained highly relevant, and it is still the best resource out there on the subject. Hard work and luck.

Anyway, public screenings weren’t happening much to my knowledge outside of classrooms, until this year, when my Google started pinging with both screening announcements and media hits.

Mitchell: OK, so you’re going along over time… a somewhat steady interest remains out there for “In Whose Honor? and then… WHAM… suddenly interest increases. Attributed directly… largely… to one big thing? There’s a football team in the nation’s capital that has been badgered by protesters, etc., consistently through the years, but no real movement, and certainly no interest among owners and fans to lose the name. All of a sudden this team is getting a lot of press over the issue, due to legal challenges. So what happened exactly?

Rosenstein: The inciting incident was the June decision by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office to remove the trademark protection for the Washington R-skins team name and logo, based on a lawsuit led by a Navajo woman, Amanda Blackhorse (Blackhorse v. Pro-Football Inc.). The decision started a massive national media firestorm, as well as an interesting connection for the film: seeing “In Whose Honor?” for the first time as a student at the University of Kansas was one of the things that inspired Amanda Blackhorse to lead the patent and trademark complaint in the first place.

But, there’s been a real measurable evolution on this issue in the mainstream. Because this is the 2nd time the Trademark office ruled this way, so we can compare the reactions from each. The first time, there were a few media mentions and not much else. But in the nine (?) or so years since that ruling, public opinion has changed dramatically towards the American Indian side, and certainly all those classroom screenings of “In Whose Honor?” have played a major role. On the heels of the June ruling: the Daily Show did a segment making fun of the R-skins fans; South Park did a great satire of the owner of the Washington team on this issue; the New Yorker satired it on their Thanksgiving cover; Bob Costas, perhaps the most famous national sports announcer in America, came out publicly on the side of dumping the R-skins name; and several media announced they wouldn’t print the name and several sports announcers said they wouldn’t say it. I just saw a story that said the use of the name R-skins by sports announcers dropped by 27% this season (only saw the headline so don’t know how that was measured). When I first heard that Bob Costas came out publicly against the Washington R-skins name on the air, my reaction was that we must have just hit a tipping point, because for someone like him to say it on national sports TV, in front of that multi-billion dollar industry and its multi-billion dollar sponsors, it must finally be a safe enough position to take. It’s similar I think to LGBT issues: twenty years ago no one on mainstream television would ever say something supportive about lesbians and gays; now, it is a completely safe thing to do. Anyway, I am sure that part of what has made this issue a safe one for TV is the many years of “In Whose Honor?” screenings in schools, and educating people on the issue one class at a time, over eighteen years. It is beginning to reach a critical mass.

Here’s another example: there’s a radio sports talk show in Chicago, call-in kind of stuff, called Boers and Bernstein. Years ago, maybe 12, they had Steve Kaufman, who was very active on trying to rid the University of Illinois of its American Indian mascot, Chief Illiniwek, on live via telephone after something about the Chief and Steve broke in the Chicago newspapers. They totally criticized him and insulted him so much that he finally called them “assholes” on the air and hung up on them! Fast forward to last week, when a Chief Illiniwek performance was canceled at a high school in Tuscola, Illinois, and the same guys on the same show talked about it on the air. But this time they completely ridiculed Chief supporters as “hayseeds”, mocked them about whining “it’s a tradition” and called Chief Illiniwek “1-800-Dancing-Clown”. It was a stunning turnabout.

Anyway, that Patent board decisions inspired a lot of people, so when the football season began, there were some major efforts made to protest the Washington team wherever they played. The protest in Minneapolis was the largest ever, reported as over 5000 demonstrators. Why Minneapolis? It’s the birthplace of the American Indian Movement, so there’s a long history of Indian activism there. There was also protest in Washington for the last game, reported to be the largest at that stadium ever (over 1000 people, in a VERY hostile and dangerous environment). Screenings of “In Whose Honor?” piggy-backed on many of these protests — in Minneapolis, where the film screening was introduced by the President of the University of Minnesota, Eric Kaler, in San Francisco at SF State University, at the University of Chicago, and even coming up, as part of the Super Bowl week events in Phoenix.

Mitchell: So, documentaries are made for a couple of reasons… to increase awareness of a particular issue, but also to motivate people to take action. Maybe you have other reasons to add to the list, but… my question is: Why did you make “In Whose Honor?” in the first place? What were you hoping to accomplish?

Rosenstein: I made “In Whose Honor?” because I felt more people should hear what Charlene Teters had to say about the mascot issue. I also made it hoping that it would be a tool for activists to use when giving talks and organizing around this issue. I never felt that the movie itself was going to lead directly to action. I mean, what action would you take? Call Washington R-dskins owner Dan Snyder on the phone? But I thought it could be an effective tool to help motivate people to join with the people who organize actions. I’ve always felt that social change requires all kinds of different contributions from people. I’m not an organizer. But I know how to make a movie. So this is how I contributed to the movement. And social change also requires that a lot of minds get changed. I thought I could help do that too. But the main thing I wanted to accomplish was getting rid of Chief Illiniwek and every other American Indian sports mascot, nickname, and logo.

Mitchell: And, of course, the follow-up question is… have you accomplished your goals?

Rosenstein: Some. There are far fewer of these mascots and nicknames than there was when the film was first released. The film has been used in many of those successful campaigns. It also played a part in the 2005 NCAA policy to penalize all member schools that didn’t get rid of their American Indian mascots, logos, and nicknames. The NCAA contacted me in 1998 to get VHS copies of the film (that’s all there was in 1998) for every member of their minority affairs committee, because they were beginning to research the issue. And that ultimately led to the end of Chief Illiniwek, which was probably my number one goal. The film was also included in the case file in the first Patent and Trademark Board case that was brought by Suzan Harjo. So it has had an effect.

Mitchell: After all these years, what have YOU learned from making “In Whose Honor?”? What’s your own take away from its success and endurance?

Rosenstein: I learned about the potential power of documentary to educate, to change minds, and to impact social change. And I learned that this form of media, unlike many others, has the potential to have a long life and be effective for a long, long time. I think the film will definitely outlive me, which is both a weird and beautiful thought at the same time.