Language is a strange thing. It might not be unique to humans, but the ways we use it seem to be. It nourishes us. As semantic sustenance, we ingest it, digest it, and break it down, extracting the meaning and feeling necessary for growth. We can also use it to nourish and enlighten others. It is a vital component of our (shared) existence: no two of us view the world in the same way, and language allows us to weave links and forge understanding between the nebulous aether of my collected life experience and yours. In this way, it is a prime facilitator of love, commerce, learning, empire, even death. Language lives and dies, too. It grows, and its growth often reflects our growth, as individuals, as societies, as a species. In an age of globalization and hyper-specialization, new words are coined all the time. And yet, one frustrating but all-too-commonplace aspect of the human experience is the inability to find the right words (especially at the right time). We get overwhelmed by grief and affection, and we stand witness to things that seem almost impossible to describe. Effective expression and the language necessary to build understanding takes work, patience, and skill.

There’s also the tricky realization that language is a collection of signs and symbols with socially agreed upon meaning that often approximates and abstracts the human experience so that we can talk and write about it, while necessarily sacrificing immediate nuance and detail. To exemplify this, let’s examine the case of love. There are a few generally agreed upon definitions of love and our adroitness in finding new ways to use this idea facilitates conversations and the sharing of experiences about parents caring for young children, grown children caring for elderly parents, patriotism, dating, hooking up, marriage, divorce, and much more. But the somewhat awesome reality of the situation is that there are as many definitions of love as there are people and that each is a little different from the rest. To get a more accurate idea of what love means to an individual, you’d need to engage in a dialogue, using other words, ideas, images, and examples, to slowly merge your two circles of experience together to get that sliver of overlap in the Venn diagram depiction of your interaction. Maybe this sounds like a challenge (it is). Maybe it sounds exhausting (it can be). Maybe it seems like an endeavor doomed to fail (it does, frequently). However, it’s plays a prominent role in the human experience and for many, the pursuit of mutual understanding, of navigating the vast but strangely limited linguistic resources at our disposal to understand and be understood, is a worthy pursuit.

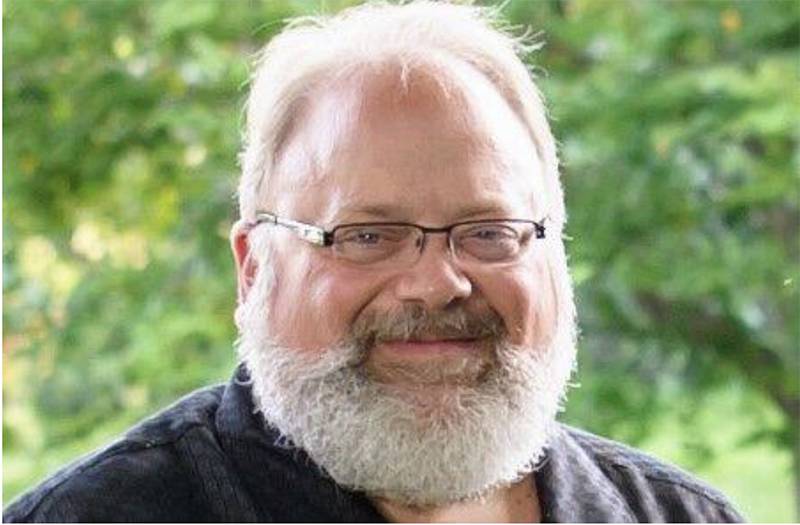

Will Reger, Urbana’s inaugural poet laureate, is one such soul. And thankfully for anyone reading this, his musings on what it means to be human are much more elegant, pithy, and playful than the philosophizing of yours truly. In A Living Vocabulary, a poem from his new collection, Petroglyphs, he explores the limitations and possibilities of language, writing:

We could argue only so many words

exist in language that catch and hold us –

But who are we once those words are used up?

A desert that offers us nothing more.

I’ll squat in your shadow on those hot sands

and pray earth mother for water – I know

you see no need for color, and mistrust

the dew that could heal us both with its touch.

But I see wild flowers, lambs on the hill,

and us, drinking in all new words for love.

Petroglyphs, Reger’s first full length volume of poetry, is filled with similar metaphysical meditations, intricately crafted scenes, spaces, moments and feelings that afford the reader ornately wrought windows into his particular perspectives on life and love, nature and the nature of historical thought, grief and death. In a way, reading his collection feels akin to cracking his head open and reveling in all the dreams, vignettes, and explorations (both taken and yearned for) that come spilling out. It brims with vivid experimentation with time and space, color and texture, collocation and metaphor to render images that are both personal and more widely resonant. Reading Petroglyphs, you learn about Reger and about yourself.

The collection is also a love letter of sorts to language and all the possibilities it affords a person willing to sit, think, and tinker with it. In his poem, Essays on Knowing, he writes:

The willing mind knows

that dreams

are fishhooks scattered out windows.What will they catch

in the wild streams

that flow down from

the mountain of learning?A spidery fire? A verb? Persimmons?

The rain as a metaphor for yearning?The willing mind will find

connections

It also seems to posit, like his surreally delightful piece, The Magic of a Poem, that poetry facilitates mutual understanding in valuable ways precisely because it often eschews the literal for the figurative and places interpretation at the forefront of the meaning-making process. Part semantic architect, part unabashed dreamer, Reger takes subtle moments, some unique, some quotidian, and distills them into a tightly knit collections of images and sensation realized to create feeling, to share insights, to offer his interpretation on the defining features of life, his life and ours. The words are the means, conveyed, as noted in the forward, with “spare, powerful directness”, but it’s the images that persist. In this sense, this collection is aptly named.

Petroglyphs is a slim volume (less than seventy pages) but it is impressively diverse in tone, style, and subject matter. There’s humor (the cheeky He Made His Own Supper), lyricism (An Old Song), and a modern historical epic (the powerful, resonant, and very timely verse of The Old Country). There are also a few themes that he touches upon and returns to throughout the book. Nature and the natural world are frequently invoked. He contemplates the light of stars, poses questions to hummingbirds, and personifies a river. In Prairie Restoration, a beautiful ode to the grasslands that once dominated this area, the titular rejuvenation project is depicted as a wary truce between man and the wild born, in part, by human guilt stemming from “Pogroms of the plow” against nature, with the now contemplative narrator noting:

We have battered the soil

for more than a hundred years,

but healed here

by establishing a zone,

a sort of DMZ

for ironweed and clover,

for blazing stars,

Indian grass and spurge.

Death’s necessity and the transformations it ushers in (revitalizing and otherwise) are another common theme. In Essays on Knowing (if you haven’t guessed already, this was one of my favorites), he writes:

Last spring two wolves brought down

a deer:

sweet meats first, marrow, then haunch.

All summer, beetles worked to clear

the last of the flesh from the shadowy

skull.Then bees, hovering in and out

the sockets of that whitened cathedral,

laid in their honey, golden sweet.

Love and the many forms it can take is another central theme throughout the volume, though he approaches the topic in unique and often unexpected ways. While A Valentine’s Poem has little to do with that most commercial of “holidays”, Reger takes a backpack and transforms it into the journey that comes with sharing your life with another in The Rucksack. First impressions deceive, and close reading is rewarded throughout the book.

Finally, there are several poems scattered throughout the collection that mine quotidian life for moments of insight and beauty. These poems are some of my favorites. In them, Reger employs his keen eye and way with words to illuminate the passed over, the tossed aside, the visual background noise of our daily lives in surprising, empathetic, and clever ways. One of these poems (maybe the best one) is Returnables, an ode to a discarded bottle, one whose potential Reger holds in high esteem, a salvation story told in trash. He writes,

Despite the filth and indignity

you have suffered in your pursuit

of offering relief from darkness,

I know your worth, your purpose,

your sassy sparkle, the cold pleasure,

the very apex of your dream,

now forgotten by everyone.It is the same for us all:

release, emptiness, and you are lost,

tipped and tupped and tossed.

But you are returnable –

you will be redeemed.

We live in a time where the majesty and power of language is underplayed, often ignored, and usually taken for granted. Thankfully, we still have a dedicated faithful like Will Reger carrying the light and showing the rest of us how to use language to enlighten, to connect, to translate the ineffable, and to explore. The poems of Petroglyphs are a welcome reminder of the joy and value that can be derived from using words to explore life and the world. The poems, much like the stone carvings alluded to in the title, humble, inspire, and challenge. Ultimately, there’s so much more to be discovered, and through his poetry, Reger urges readers to take the time to engage with the world around us more carefully, more thoughtfully, at a slower pace, with greater depth. In Essays on Knowing, he shares his rallying cry:

The unknown is endless; your mind

has room.

Personally, this seems like a pretty clear exhortation to go out and explore, to fill oneself up with life. Of course, another reader might interpret these lines differently. If so, I’d encourage them to come find me, so we can discuss.

Will Reger will be reading selections of his work as part of the Poet Laureate’s Showcase, which will also feature local poets Mariana Machado Rocha, Elizabeth Majerus, Ann Hart, Jim O’Brien, Indrani Sengupta, Kevin Tajzea Hobbs, Michael Peirson, Elaine Palencia, Ashanti Files, Amy Penne, and James Engelhard.

The Poet Laureate’s Showcase

Urbana Free Library

210 W Green St

Urbana

February 13th, 6:30 to 8:30 p.m., free