There is currently a free exhibit at the Illini Union Art Gallery that is well worth seeing. It’s called Lost Poland: Images from the Border Protection Corps, 1935-1939, and will be on display until January 21st. The exhibit consists of 16″ x 20″ black and white photographs digitized by the University of Illinois Library from film reels made by the Polish government in the 1930s. The filmstrips were originally made to depict an idealized Poland during the years between the two world wars and were shown by the Border Protection Corps to their recruits in order to make them feel more patriotic. Click here to check out images from the exhibit.

Basically, the images reflect the filmmakers’ desire to show Poland as both modern (factory workers making cars and light bulbs, etc.) and traditional (castles, peasants working in a field with hand tools, etc.).

I spoke recently with George Gasyna, one of the curators of the exhibit, at the Illini Union Art Gallery. He is an Assistant Professor at the UI in Slavic Languages and Literatures.

Loss

It says in the exhibit literature, “The concept of loss manifests itself in multiple ways in this exhibition.” Indeed, instances of loss can be found in the back story of how the exhibit itself came together. Gasyna explained, “It started in the attic of my co-curator Jo Kibbee, whose family was from Poland. She happened to have these three boxes of film reels made by this company Ornak, which doesn’t exist anymore. It was a prewar design and film company and their building was destroyed in the war.”

A relative of Kibbee — an American of Polish descent who fought in the European Theater of World War II — somehow got in touch with some Poles and obtained the film reels that were eventually used to make the exhibit. Gasyna wasn’t entirely sure why the relative did this in the first place, but in any event, “He rescued the reels and brought them to the States where they stayed in the family for a long time.”

Decades later, Gasyna and the other curators began to realize the value of the reels in the attic: “We started looking through these boxes one day and realized what we had in terms of the whole iconography of the mid-thirties.”

He said that images in the exhibit of objects frequently photographed in Poland in the 1930s — bridges, buildings, etc. — have photo angles and perspectives that aren’t generally seen: “It shows an aspect of images that might not be part of the collective imagination of culture in Poland before the war.”

A few other reels from the original filmstrips are known to exist today in other locations, but much about these films has been lost, just as much of the Poland they show was lost in World War II. Gasyna explained that part of the curators’ motivation for bringing the images to the public was to try and find some of the missing puzzle pieces: “We found some extraordinary images that we wanted to share with the community here. But we also wanted to complete the story, because the main thing that’s missing — the major loss — is the accompanying text.”

Basically, the hope is that, like the reels in Kibbee’s attic, the scripts to the filmstrips are out there somewhere and someone who has them will get in touch. There’s other information that is hoped to be recovered as well, including details about who did the actual filming.

Mystery

Part of what makes these images intriguing is that, in some cases, it’s difficult to figure out exactly what is happening. A good example of this is Border Corps Soldier with Street Vendor (see picture below). What’s going on? What kind of body language is that for a soldier? What’s in the cart? What’s up with the street guy?

Gasyna said,

I don’t really know what’s going on. I’ll buy a beer to the best answer. To me, it sort of shows the smiling patriarchy of the army. During this time the opposition was allowed to exist, but the army was in charge until the very end, until 1939. The generals were running the place.

I think this is a chestnut roasting cart. Then there’s this street kid guy confronting the camera in front of this very industrial, large scale building. And then there’s this very placid, but in charge, figure. To me, it’s sort of like, ‘We see you; stay sweet.’

Gasyna mentioned another image — a baffling one that didn’t make it into the exhibit for reasons of space — of a woman giving cheese to some children. Are the children starving? You can’t tell from the picture, he said.

Another mysterious aspect is that it’s hard to read facial expressions in many of the shots. Part of this is that the pictures are old and sometimes indistinct, but even with clear shots there’s a lot of ambiguity.

There are few smiles, of which Gasyna — who is originally from Poland — said, “I went back to my own family albums and you don’t really see a smile until 1960 or so. You see these very somber, serious poses.”

He also mentioned that some of peasants in the filmstrips may never have been photographed before.

Many of the images are in the eastern regions of Poland, near the border. Gasyna noted that, “This was the poorest and least advanced part of Poland.”

The filmstrips were supposed to make the ethnic groups in these borderlands feel more like part of the larger nation, and identify more with Poland than with any other cultural or national group, especially Russia. At the same time, the filmstrips were meant to make the rest of Poland — in particular the recruits of the Border Protection Corps being sent to the eastern region — see the east as less backward and provincial.

What kind of national identity imagery is this anyway?

As it says in the exhibit literature, there are images of “hearty peasants in a bucolic countryside,” as well as “noble workers in clean and prosperous factories.” This makes sense, since the main point of the filmstrips was to raise national pride.

Sounds a lot like propaganda, right? But, the thing is, these images aren’t TOO idealized. The peasants aren’t beaming; many of the factory workers are shown doing tough and dangerous jobs. Also, many of the images do not appear to be staged.

I asked Gasyna about this — the relatively mild imagery in a time when, in nearby Germany, national identification with the Fatherland was being raised by propaganda films, such as Triumph of the Will through very bold strokes.

Gasyna replied that, in Poland, at least, in a time of economic depression, pictures of “really happy peasants would not have gone over well.”

He continued, “This is just a sampling of about 20,000 images. And we tried to work from really good quality originals, which meant that there were entire reels we couldn’t use. That includes reels of serious military propaganda, for example. Or reels of hardcore industrial charts and statistics.”

To me, the images in the exhibit don’t look like propaganda at all — or if it is propaganda, it’s a mild form of it. As Gasyna said, “There are no torchlight parades.”

“Don’t panic” or just clueless?

In fact, the calm — the understatement of the images — is startling in the context of what happened in Poland just after they were made. Even the casual student of World War II can tell you that Poland was pretty much destroyed after it was invaded in 1939, but, from these images, you wouldn’t guess anything all that bad was about to happen. The soldiers don’t seem uptight, the factories aren’t full of war production, and the countryside generally looks a little sleepy.

I asked Gasyna about this. Were the filmmakers trying to assert a sense of calm because the government — knowing what was coming — didn’t want people to panic, or did Poland genuinely not know that war on a massive scale was coming?

Gasyna replied,

That’s really a question for historians to grapple with for some time to come, but my personal sense is that there is a war about to happen, but there’s also a sense of denial ― they just had a war, right? If you look at the years ’37 to ’39, I would say that the main sentiment is denial that these two regimes, Germany in particular, are going to try again to get these lands back.

But at the same time, there was also a lot of military preparation going on in Poland. Alternative history being what it is, a lot of people say that if the war had started in 1940 things would have been very different because Poland would have been more ready. Poland would have prepared their special high-end airplanes, and other things. There was quite a lot of research and development going on. And the Nazis knew that.

As late as mid-summer, 1939, even June, people thought, ‘There will be a war of some sort, but certainly not now; it’s such a beautiful summer.’

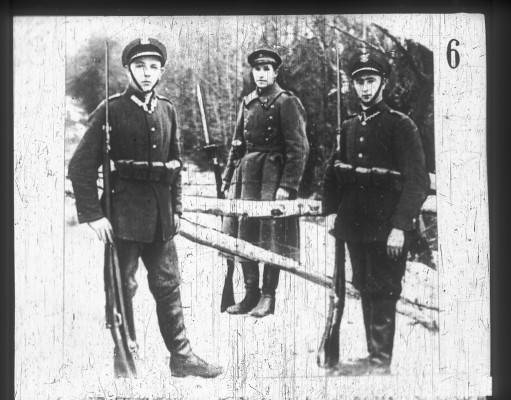

Gasyna pointed out how unconcerned the Polish soldiers seem in the photo Border Patrol Corps (Korpus Ochrony Pogranicza) (pictured below). “It’s just so casual, clearly in a time when Hitler was in power. It’s no earlier than ’35 or ’36. And I found that very striking, that this massive force was at the border — this genocidal kind of force in Germany — and the guard is so relaxed.”

Impressions

To me, these pictures seem eerie. Images of ghosts before they’re dead. Part of my reaction comes from knowing what happened in Poland after it was invaded in 1939. I find it unsettling to look at peaceful images like Countryside along the Coast (below) knowing that there’s a good chance the person sitting under the tree was dead from the war a few years later. The aesthetic qualities of the images — black and white, mysterious faces, a sense of quiet — add to this.

Gasyna said of his own impressions:

It’s interesting; I don’t feel sad looking at these. I feel sort of … numb. I’m looking to point fingers, and my finger is pointed at the generals who ran the country who were squabbling amongst themselves. There were sort of two wings, left and right, and it was sort of like what we see now here in the States where everything that was put into parliament would be blocked by the opposition. Nothing was being done; it was a complete deadlock. Once they realized that there was this war that was going to happen, it was too late.

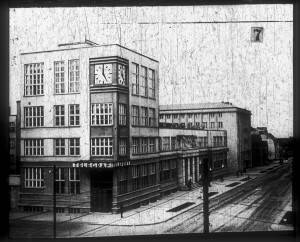

My own favorite image in the exhibit is Telegraph Building, Gdynia (pictured right). Gasyna gave me some historical background to go with it:

My own favorite image in the exhibit is Telegraph Building, Gdynia (pictured right). Gasyna gave me some historical background to go with it:

This whole town was built in the ’20s as sort of an Art Deco village. You can see the power grids, the clean angles. Light, clarity. The city was built in just a few years. Many of buildings were copies of very modernist structures in Germany, Holland, Belgium, England and France. It survived the war and has been restored, and even though it’s not wholly original, you can still have the experience of driving through a ’20s city now.

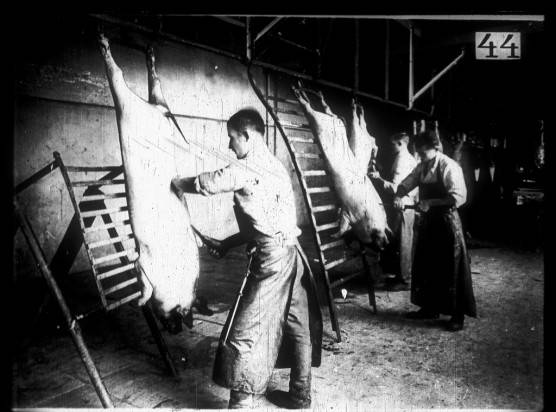

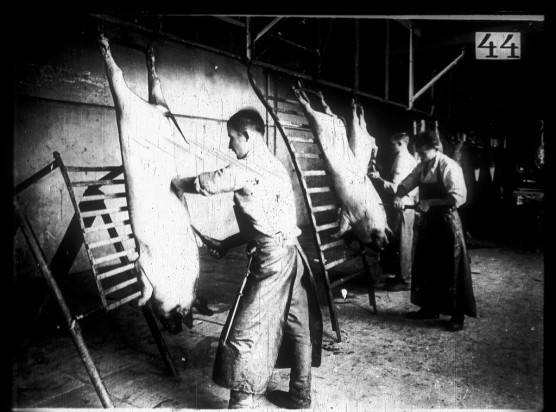

He mentioned that his own favorite image is Hog Butchers.

A delayed vision of Poland?

These filmstrips made Poland look better than it actually was when they were produced. But now, as 2011 begins, things really are going well in Poland. The country is independent, doing relatively well economically, and so forth. I asked Gasyna if the filmmakers’ vision of an idealized Poland eventually became reality, but just 70 years or so after the fact.

He replied, that, yes, the idealized Poland of the filmstrips has, at least in part, come true today:

In the sense of having an imagined homogeneity where everyone is Polish? They have that now. They also have a successful, established country with several senses of security — NATO being one of them, the EU being another one — which means that you can’t just go in and invade. Which was what Polish history had been about ― kind of just staving off invasions.

In conclusion

Explaining what makes these images so moving, Gasyna said, “It’s that frozen moment before a holocaust. Before the juggernaut of history,” and their historical context is certainly part of their value. In any event — part detective story, part intriguing photography, and part incomplete time capsule — this exhibit is something different and remarkable.