Like their colleagues in performing arts schools around the world, the students and faculty at the Lyric Theatre at Illinois have been challenged to find safe and meaningful ways to teach, learn, and perform in a pandemic. Under the exceptional leadership of Lyric Theatre co-director Julie Gunn, they have not only found new ways to create and share their work; they have embarked upon new collaborations. Smile Politely spoke with Gunn about teaching and creating during COVID, and the Lyric Theatre’s Salon Subscription and its recent and upcoming offerings.

Smile Politely: In the ShowTalk interview that you and Nathan did with Matt Boresi and Peter Hillard, you said that KCPA is the third site of production for this opera, after UrbanArts in Arlington and Pittsburgh Opera. How did Krannert choose to produce Last American Hammer?

Julie Gunn: Lyric Theater always wants to be an incubator of new work for the industry. As to how we did it, Michael Tilley (of Lyric Theater) knew Matt and Peter already, and when they came to see KCPA’s production of Little Sharp Ears in 2019 they played some of Last American Hammer for us. Fast forward to trying to produce things for this spring: I asked the Lyric Theater faculty if they could name pieces they were interested in with small casts and small orchestras, and Hammer came up.

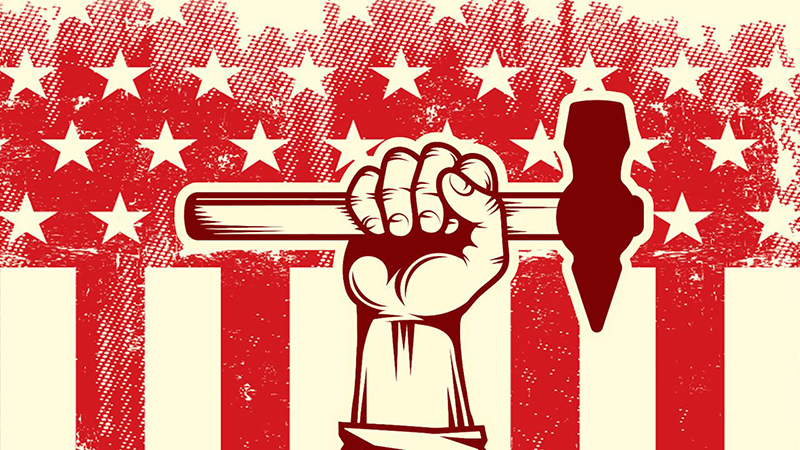

Image from the Lyric Theatre Facebook page.

SP: Where, or how, did Last American Hammer fit in Lyric Theater’s repertoire? Is it the kind of production that people know Lyric Theater for?

Gunn: What we hope people know us for is a range of types of sung theater. I would say that we are not a political organization. We don’t really embrace art for … that kind of thing, for ourselves, but we do like to be relevant more than political. This show [Last American Hammer] talks about political issues, but does it from an artistic point of view.

SP: It’s good art that happens to be political, which is different from a political idea that someone could make art out of.

Gunn: That’s what it is, and that’s very much what we prioritize doing. In the ShowTalk interview—which I thought was so right—Matt and Peter saw a structure that allowed them to treat each character as a whole human being. I very much like that POV. I also like our students, the performers, to work with living people at least some of the time, and I also like them relating what they’re doing to something in their own lives. That said, you can relate The Marriage of Figaro to something in your own life, but it’s a longer “walk.” I actually don’t feel like Last American Hammer is that different from The Marriage of Figaro in the way that they treat people. The thing is that Mozart and DaPonte have been dead for some time, and there’s a lot of recordings of Mozart that make our students compare themselves to other people and get kind of a self-conscious “classical music monkey” on their back.

SP: Agreed—in Mozart there’s plenty of humanity to be unpacked in his characters, but the expectations make that unpacking happen in more layers. In Last American Hammer, as a new opera, those years of expectations just aren’t there.

Gunn: Bluegrass opera, on the other hand, which Last American Hammer is, has not been a part of Lyric Theater’s core repertoire before now. Last American Hammer is many people’s first bluegrass opera. It blends approaches—I’m always finding myself talking to the singers about thinking about the blues, and it has lots of those influences in it.

SP: Has that basis [in blues and bluegrass] helped the students performing get out from behind the “classical music expectations” that they might bring to opera?

Gunn: Yes. I talk to them about that a lot. And I would say that there’s a constant conversation [that we’re having] about the difference between opera and musical theater, and the conversation between the elements of both traditions.

I think that classical musicians—really any musician who has gone to music school—has spent an overwhelming majority of their time preparing from a musical point of view. And we’ll have the same issue with Marriage of Figaro in the Spring. They’re very good at learning the music, and they can translate the Italian and they know what vowels and consonants to use. The music that we’re setting them is extremely difficult. Hammer is difficult. Figaro is difficult. The Turn of the Screw, which we just finished filming, is difficult.

Photo from the Lyric Theatre Facebook page.

Where I feel like I have to come in as an educator is that they don’t yet think from a text point of view. So you’ve got people singing, I don’t know, [she sings] “I turn on the light!” but they don’t feel quite licensed to move beyond the music they’ve learned. Most of the people who come in from a Musical Theater point of view come in with a “text & storytelling first” attitude, and it’s our general goal at Lyric Theater to have good solid musicians who are committed to telling stories.

SP: In terms of stories, I’m really fascinated by this character, Milcolm Negley because it’s not often that we see a character of this positionality—a white, working-class, conspiracy theorist—at the center of something like an opera. We’ve seen characters like this before, but they’re usually to the side somehow. And I know there’s a point in the libretto where he critiques the NEA, which has contributed funding to the museum that he’s taken over.

Photo/screengrab of Showtalk from the Krannert Center for Performing Arts Facebook page.

Gunn: All of the characters have many overlapping identities, and that really makes for compelling material.

[Composer Peter Hillard and Lyricism Matt Boresi discuss their character work in the ShowTalk video here.]

SP: What has planning this as a live production been like?

Gunn: One thing about COVID performances that I’ve learned is: because you can’t have that many people, and you need to be really careful for the audience’s safety, they [the audience] don’t have a lot of habits when it comes to this. So you have to give them more guidance, and I’ve been learning how to do this in a way that is aesthetic and welcoming, instead of just putting up crime tape everywhere. I’d rather be the usher myself (which I will be); we know who’s coming, as well, and I think that’s a gain. Performing for an anonymous audience is very different, and there’s something really nice about it.

SP: It speaks to a limitation acting as a creative force instead of a limit as something that prevents a production from being what it “should be” in a conventional space.

Gunn: Exactly! We were very much trying to do that. … I think I’ve learned more this year than I have during any other year, with the possible exception of my first year. The limitations are just different. And then there are some things, like the Senior Showcase, that I would never go back to. Filming them instead of having them live meant that we could really had more ways to show our students performing as their best selves. We caught some things on film that we never could have planned—one in particular happened backstage, so we could only have caught it on film—and those recordings can then be sent all over the world, however the students would like to use them.

Learn more about the Lyric Theatre at Illinois’ salon subscription, including the upcoming production of Taming of the Shrew, here.