Howard Finster Exhibit | Krannert Art Museum

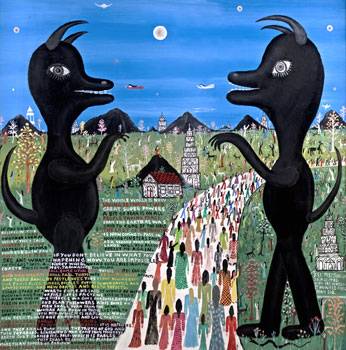

Howard Finster might just be the most American artist of the twentieth century (the reader should feel free to contest this in the comments below since your assigned correspondent has a startlingly limited background in Americana). To gloss terms, American is here being used as an amalgam of nationalism, consumerism, religious zeal, prodigious factory-like output, genuine esteem for both Hollywood and the banjo, healthy doses of paranoia and absurdity, and an undying earnest showmanship. His work is crude, but polished and incredibly colorful. Perhaps it is ultimatley the product of a sincere effort in what might not be the most capable of hands, though it is visually stunning nevertheless.

The first thing that hit me at the Krannert Art Museum was the sheer volume, and the two rooms there could barely come close to containing the reported 46,000 works produced over a lifetime. Such an effort would seem a Quixotic task since numerous artifacts were sold in a roadside museum or given away. Finster explained this volume of output in an interview with Johnny Carson saying that, since he’s retired he doesn’t sleep and so has twenty-four hours every day of doing what he wants to do. Not that preaching in a suit-and-tie seems was undesirable or even a chore to the joyful showman who capers and spreads an absurdly original interpretation of the Good Book in nearly every piece cataloged.

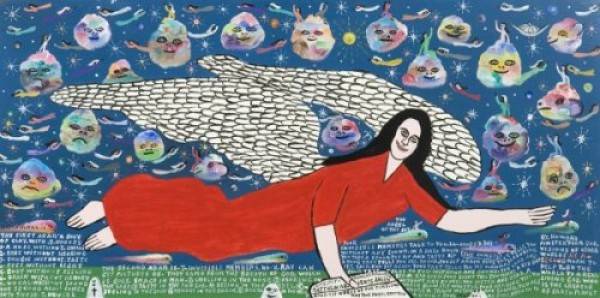

When you enter the exhibit you see an angel, you hear Finster’s voice, a high whistle-y Southern twang, and laid in tables under plexiglass, you see… basically a bunch of crap. Postcards from the fabled Lookout Mountain outside Chattanooga, TN, as well as every other type of roadside tourist trap, from alligator farms to Finster’s own curious museum, nestled in rows next to books of personal revelation. All across the walls are wood-cut frames with star-like patterns stamped and burned into the crudely nailed casing. So much painting is done on thin sheets of wood with enamel tractor paint. Or else it’s done on glass. The painting itself is a mixture of psychedelic 60’s acid-influenced art and a pre-Renaissance lack-of-understanding in perspective.

Subjects range, but misspelled Bible verses feature prominently, usually in all caps. There are naked, groping, one-eyed devil children. There a lots and lots of presidents. Lots of Elvis portraits. Lots of family and friends, some embarrassing self-portraits. There’s a Coke bottle that simply talks about how everybody likes Coke. Even church people like Coke. People will stand on their heads for a Coke and then drive home safely. I’ll draw some upside down heads forming a band around the bottle. He has a habit, in all of his portraits, of trying to painstakingly recreate the peculiar part of the human anatomy that connects the nose to the lips. He makes it ugly, though, every time.

Perhaps most frequently, as far as an individual subject goes, there is a portrait of Henry Ford at two years old with a plait of dark-brown hair forming the curvature of the left side of his face, his right side bare and smooth, his eyes saucers under a wide-brimmed hat. He looks much more like a little girl than a wealthy, powerful anti-Semitic industrialist. At one point, you can see a sketch of Finster’s next to the original photograph he mimicked, and you see that the artist was painstakingly trying to inscribe all of the nuances in the face that he saw in the picture, of detail but not shade, failing to recreate in so many marks of audacity. There is no subtlety in Howard Finster’s art.

Finster’s work, for me, succeeds most when he puts to use all of the crap he can in one work. There are pieces in the exhibit that show several layers of physical texture, one wood-cut laid over another to reveal interesting ways of incorporating negative space so that nothing is left bare on the work, everything is filled-in somehow in a vibrant way. A house, raised up physically from the background, is split in the middle, the windows are cut out and drawings show through on the wood beneath them, the split itself, in a gap at the bottom, shows the words, “the gap.” Everything is integrated into one pulsing piece. When Finster draws on glass, especially, he fills in the whole background with ornate squiggles, inlays cheap plastic diamonds for the decorative feelers of the insects he draws and leaves no stone unturned.

Finster’s work, for me, succeeds most when he puts to use all of the crap he can in one work. There are pieces in the exhibit that show several layers of physical texture, one wood-cut laid over another to reveal interesting ways of incorporating negative space so that nothing is left bare on the work, everything is filled-in somehow in a vibrant way. A house, raised up physically from the background, is split in the middle, the windows are cut out and drawings show through on the wood beneath them, the split itself, in a gap at the bottom, shows the words, “the gap.” Everything is integrated into one pulsing piece. When Finster draws on glass, especially, he fills in the whole background with ornate squiggles, inlays cheap plastic diamonds for the decorative feelers of the insects he draws and leaves no stone unturned.

The most interesting thing about the Finster exhibit, though, may be the complete lack of xenophobia espoused by this man. Working in the time he did, from the middle to the end of the twentieth century in an artistic space isolated from the wider world, predominantly, and plunged like a fish out of water into Hollwood, the Library of Congress and crowd after crowd after crowd, Finster never produces an anti-homosexual tirade, never turns socially-illiterate against minorities and never utters a word damning America for its refusal to prepare for the Apocalypse by setting itself straight. He paints people of different colors frequently, though it should be noted that there seemed an odd trend to color the hair and lips of brown women and men with silver, especially in work created in the late 80’s.

Perhaps it is xenophobic of me to even be refreshed by such.

No, it is xenophobic, I won’t deny it. But, for me, Finster is a startlingly idiosyncratic and unapologetically antidote to the strident hate speech of more prominent Southern evangelicals like Billy Graham, Ted Haggard, Jerry Falwell, and Pat Robertson.

This, for me, seems to de-fang the evangelicals as a movement, because if Finster was a part of any movement, it was certainly one of his own making. He was an individualist. While Pat Robertson is content to make historically blasphemous assertions about the relationship of Haiti’s residents to the devil, Finster is more likely to make a revelatory trip to another planet and be united in Christ with the green people he finds there. And this is another token of Finster’s unapologetic patriotism, because he may just be the unrealistic zenith of individualism and originality that we all strive to attain.

So, did I convert to Christianity after seeing his work?

God no.

And since that’s the artist’s goal, it may be correct to call him a failure. But this is “Outsider Art,” “Folk Art,” it’s an exhibit in a museum, and it’s a curiosity with its own aura. I can’t do a non-contextual viewing of this art since H-Fins, the man himself, claimed that, “You don’t have to be a perfect artist to work in art.” Clearly. Someone worked pretty damn hard in art without knowing a damn thing. Outsider Art is necessarily coupled with a story. For example, Henry Darger produced hundreds of vibrant scrolls illustrating a 15,000-page novel he wrote while living alone in a tiny one-bedroom Chicago apartment for his entire life after escaping from a downstate asylum where he may have been something of a child slave. With no family and no life outside his apartment save his day-job as a janitor, nobody knew a thing about his work until he died.

(See Howard Finster rock the Banjo)

Finster’s story goes something like this:

Howard spent his adult life preaching in rural Georgia and retired. He came to art, in an oft-repeated story in the exhibit, through a visionary interaction with a smudge of paint that formed a human face. He had visions and God told him to paint “sacred art,” so he did. And he kept doing it. Substance abuse? Finster wrote, “WHAT YOU SEE IN THIS GARDEN AND THE LAND IS WHAT I COULD HAVE SPENT ON COCAIN AND WHISKEY OR GAMBLING. SO I DIDN’T. AND HERE IT IS. ENJOY IT. THE PARODISE GARDENT OF ART.” No — no substance abuse. Social life? Family? Finster, at one point, claimed to have fifteen grandkids. His family seems to have been immensely supportive of his creative pursuits, offspring even helping in rudimentary work cutting designs and compiling orders. The man himself traveled about the country and, during his life-time, produced album covers for rock groups like R.E.M. and Talking Heads. So what, exactly, in his story excuses the quality of his work in the light of the attention he’s gotten?

I come back to it. The man is pure Apple Pie without a smidgen of self-consciousness. Or any semblance of overt racism or homophobia. Things seem to have gotten stranger for Howard later in his life-more Revelations and less Gospels. But no hate— just work. Just work and Jesus and Coke and Elvis — and you know what? Sometimes it’s beautiful.