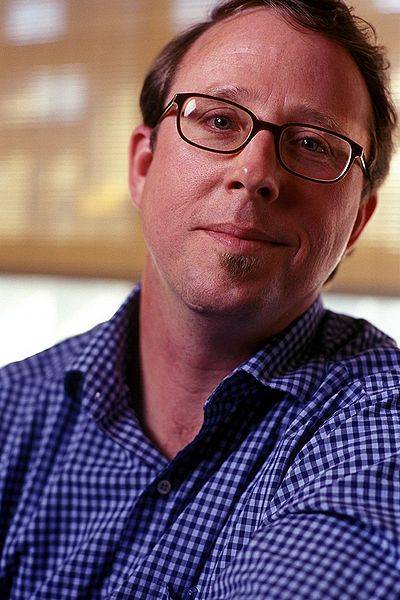

A few days ago, award winning author and New York Times columnist John T. Edge took some time out of his very busy life to give Smile Politely a little bit of insight into how he views food, culture and the many connections that run between the two. You can (and should!) catch him tomorrow, Wednesday, September 16, 2009 at the Author’s Corner in Illini Union Bookstore where he’ll begin reading from his very extensive catalogue at 4:30 p.m.

A few days ago, award winning author and New York Times columnist John T. Edge took some time out of his very busy life to give Smile Politely a little bit of insight into how he views food, culture and the many connections that run between the two. You can (and should!) catch him tomorrow, Wednesday, September 16, 2009 at the Author’s Corner in Illini Union Bookstore where he’ll begin reading from his very extensive catalogue at 4:30 p.m.

Smile Politely: Let’s start out with the obvious: you’ve written an awful lot about food. Is that what you started off writing about?

John T.: I didn’t start off to be a writer at all, actually. I’d say I fell in love with lunch first and I built a career out of that. Before I wrote, I worked in a fairly traditional corporate environment doing reengineering work. I’d often find myself working with folks who had their PhDs. My don’t-ask-don’t-tell secret at the time was that I hadn’t finished my undergrad. As time went by, I found myself taking more and more time to enjoy lunch. When I found myself making a three-hour lunch run to the Georgia coast for fried shrimp, or a four-hour run to Memphis for barbecue, I realized I might need a change.

SP: Was your transition from businessman to author an easy one?

JT: Yes and no. I was working for a firm that helped companies reengineer their approach to doing business. A part of that required me to ask folks to reevaluate their current career trajectory, and as such, I found myself doing the same thing. What I found was that I wasn’t so excited about doing what I was doing. I really wanted was find out more about where I’m from. Like many Southerners, I want to make sense of the love/hate relationship that I have with the South. So I decided to quit my job and sell my house so that I could seek a degree in Southern Studies from Ole Miss. It’s really been through that process that I’ve come to writing.

SP: So you didn’t have a pen that was burning a hole in your pocket prior to this?

JT: It wasn’t like that. I didn’t have a lot of writing stowed away in desk drawers or anything like that. To be honest, before I started back at school, I was the kind of guy who read voraciously. And drank voraciously. But didn’t write voraciously.

SP: How old where you when you finished your undergrad?

JT: [Laughs] 32 or 33. When I got to Ole Miss I quickly finished my undergrad and then immediately started working on my Master’s in Southern Studies

SP: A couple years ago, in a piece you did for NPR, you said, “After spending a week wandering the city of Montgomery, Ala., in search of the ghost of Georgia Gilmore, I couldn’t help but come to the conclusion that food — good ol’ grits and greens, fried chicken and fruitcake — has played a transformational role in this city, the so-called cradle of the Confederacy.” In what ways do you see food and culture as being connected to one another?

JT: I really see food as being a category of material culture. Ephemeral material culture. In a greater sense, it is a product of both craft and culture, as craft that just so happens to be edible. I see food as a totem of identity. Southern food has its roots in West African and Western European food traditions. I’ve come to understand Southern food itself as a crucible of black and white. Not merely sustenance, food is sacrament. A part of our identity. A representation of both people and place.

SP: In flipping through Southern Belly, the immense cultural range of the South becomes quite evident to the most casual of observers. Why do you think it is that Northerners like myself always seem a little bit surprised when confronted with this?

JT: Well the answer to that is two-fold. First off, Southerners have become very good at selling a simplistic shtick. That sort of Jeff Foxworthy meets Paula Dean thing. We’ve sold it pretty consistently over time with a wink and a nod. But it works the other way too. Northerners who come to the South looking for what’s been preserved in amber, what’s been preserved in the past, usually manage to find it, whether they’re looking for what remains of 1965 or 1865. If you come to the South looking for vestiges of the Civil War or the Civil Rights Movement, you’ve got a good chance of finding what you seek.

But the thing that delights and intrigues me about the South are the cultural contradictions that outsiders don’t expect, that I don’t expect either. Take the quintessential New Orleans coffee house — Café Du Monde for example, a place that you can go and get beignets and that classic chicory coffee. The place seems immutable, fixed in time as if it was itself dredged from the past, but once you see clearly, through the haze of powdered sugar, you realize that 70-plus percent of the wait staff who are serving this old guard food are Vietnamese immigrants. That’s what really fascinates me about the South. Those are the ironies that I really dig.

SP: It’s interesting that you mention the Vietnamese contingency of New Orleans given their historical connection to the food industry. Many of them came to work as fishermen, right?

JT: Yeah, lots are still working on boats out past the bridge pulling up the shrimp that goes into po’ boys in the French Quarter. Just around the corner from Café Du Monde, which is tourist heaven — or hell depending on who you ask — you can stop into P&J Oysters where you’ll find most of the oyster shuckers to be Vietnamese. That’s an example of a job that’s been held historically by Cajuns and African Americans. Now oysters are shucked by Vietnamese. And the world continues to spin. I like to write about a South that kicks to the curb the idealized notions of a moonlight and magnolia South. That’s a place I have no tolerance or respect for.

SP: You’ve written extensively on American classics such as Apple Pie, Doughnuts, Hamburgers and Fried Chicken. What’s next?

SP: You’ve written extensively on American classics such as Apple Pie, Doughnuts, Hamburgers and Fried Chicken. What’s next?

JT: Two things. For the past six months I’ve been writing a monthly column, “United Tastes,” for the New York Times. I’m traveling the whole country for this one. I love the South and Southern food, [but] it’s also kind of nice to get out of the Southern ghetto! [Laughs]. Working with the Times has been very invigorating. I’ve recently traveled to places like Salt Lake City and Tucson. Soon I’ll be up in West Virginia to check out the legacy of the Italian coal camp cooks who worked the mines thereabouts. I’ve had a blast doing it.

SP: So what’s the other project that you’ve been working on?

JT: I’m finishing up a book on street and truck food, which has recently been invigorated by Hispanic immigrants. The taco truck has inspired a broader restoration of the now burgeoning practice of serving street food of high quality as opposed to just slinging whatever’s cheap and easy.

SP: Some of the best tamales I’ve ever had we’re served to me out of a cooler a guy was pulling around with him from bar to bar in Ukrainian Village (Chicago)

JT: Man, I’d like to try that. Hey, have you ever eaten at one of the African trucks that feed a good number of the taxi drivers of Chicago?

SP: Can’t say as I have. You know, while you’re in the area, if you feel like some good Southern style barbeque you ought to check out Black Dog Smoke and Ale House in Urbana.

JT: When I’m not in the South, I generally try to stray away from Southern food. I want to taste local food. Distinctive food. That said, it can also be interesting to see how food travels, how fried chicken is transformed in transit from Mississippi to Illinois. Harold’s Chicken Shack is a great example of that. I’m planning a Harold’s run on the way to the airport.

To learn more about John T. visit his website. To meet him, come the by the IUB tomorrow at 4:30 p.m. All the cool people in town will be there, so you’ll fit right in!