Prologue – Friday, April 25, 2010

Prologue – Friday, April 25, 2010

11:30 p.m.: My girlfriend Miriam and I arrive at the Ebertfest Friday after party. Lest you think I’m actually someone important, I got in by borrowing some VIP passes from a very important person I know, but the truth is that they don’t check them at all, which is why I’m not going to tell you where this party is. But to illustrate what it’s been like the past few years: it changed from being held at a private residence to a larger venue, the location and orientation of which has given about a hundred or so students who have nothing to do with the Festival access to the free food and drink. It’s a little hypocritical for me, as a Young Person who tries his best to finagle his way in every year, to complain about this, but I’m not only there for the free booze. And the huge crowd makes it pretty hard to talk to Charlie Kaufman when he walks in at

12:15 a.m.: After forty five minutes of wondering if Kaufman’s going to show after his post-Synecdoche Q&A, he steps off the elevator with a couple other festival heavies. These heavies soon dissipate though, and Kaufman is trapped against the buffet, next to the table, by a bunch of nervous admirers. I shamefully join them. My goal for this festival has been to talk to Kaufman, and this might be my only chance, even though it means being one of the people who make his life harder.

1:00 a.m.: Kaufman’s clearly having some trouble with his messy Garcia’s Pizza-in-a-Pan slice of pizza. At this point I’ve edged around the buffet and am equidistant to him and the napkins. I hand him one. He thanks me. Mission accomplished?

1:09 a.m.: After Miriam initiates contact by asking about his writing method, I have a brief conversation with Kaufman which is mostly just me telling him how much I admired Synecdoche on a second viewing. I also learn trivia to share with friends: did you know Kaufman went to NYU for film production? (So Synecdoche, even though I’ve heard it spoken of as if it was a well-directed film by someone who had never been behind a camera before, was actually the work of a well trained director.)

Anyway, Kaufman was tired and probably feeling pretty hassled by people like me in the hot, crowded room insisting on speaking to him. He was very gracious and accommodating with everyone who had a question, asinine or not. But soon after we spoke, he left–a wise decision, because I stayed far too late. Open bars are a dangerous thing.

Saturday, April 26, 2010

10:40 a.m.: The Virginia has been oddly vocal this year about not bringing in outside food or drink. Not that this hasn’t been a policy before; it’s just odd that they mention it pretty often over the PA, have the ushers shout it at us after we’ve sat down, and now, as I discover this morning, they’ve stooped to checking bags. Having already dropped nigh $15 at the concession stand in 2.5 days of festival, I’m none too happy about this, especially because I’ve been carrying in a thermos full of coffee for the entire festival. And after last night they are not taking away my coffee.

I’m not trying to screw the Virginia out of an honest buck here. But in previous years, it’s been possible to get a styrofoam cup of coffee (or fill your mug) for a couple bucks in the souvenir room. This year, you actually have to buy a souvenir (a $12 cheap plastic Ebertfest travel mug) in order to drink coffee. Come on, I love the Virginia, but I bought a Festival Pass for an ungodly amount of money, and, as I’ve said, have been frequenting the concession stand. I feel like my debt to this wonderful old theater is paid. So I’ve been getting my thermos filled at Kopi for $1 and carrying in the pouch on the outside of the bag, and so far, no one has said shit.

And this time, when my thermos is discovered, the usher doesn’t have the courage to tell me to chug all my coffee right now or get out. Probably because I’m giving him the “I will KILL YOU if you take my coffee” look.

11:00 a.m.: Chaz comes on the stage and reminds us that Iceland’s volcano is keeping Bill Nighy from us. We (the audience) groan and then the film, I Capture the Castle starts.

The 11 a.m. Saturday slot is traditionally the “kids’ show,” which in the festival’s more magnanimous days, was free. I Capture the Castle is still a kind of kids’ film in the vein of A Little Princess or Secret Garden or something, but it’s got boobs in it, so here in the U.S. we couldn’t dream of letting our kids actually see it. Although the affinities kind of end here, Castle, like Barfly, is partially about writing and the artistic process. More than that, though, it’s a coming of age story about two English sisters, whose family lives in a dilapidated castle, falling for their landlord’s American heirs, and not for all the right reasons. The family’s road to recovery—the father (Nighy) was once a respected novelist but they now live in poverty—lies in making the right choices and getting over the damned writer’s block. It wasn’t my favorite movie of the festival, honestly, so let’s travel forward in time to

2:00 p.m.: Vincent: A Life in Color is a documentary about a person whom I guess you probably recognize if you live in the Chicago area, Vincent P. Falk, whose colorful suits and eccentric, um, dancing (?) are a mainstay of the Chicago River tours, and apparently, Friday mornings on NBC News Channel 5. Also known as “Riveracci,” Vincent stands with his tacky and flamboyant suits on the State Street bridge, twirling and swinging his jacket at the tourists on the boats below. As the documentary admits, if you saw Vincent on the street you’d probably dismiss him as a “crazy,” with his strange suits and odd posture and manner. But beneath the fuschia three-piece, as the documentary shows us, is a relatively normal guy (with a respectable long-term job with Cook County) with acute glaucoma (he’s almost completely blind but usually gets along by himself, hence the observably strange posture and manner) and a desire to be noticed.

2:00 p.m.: Vincent: A Life in Color is a documentary about a person whom I guess you probably recognize if you live in the Chicago area, Vincent P. Falk, whose colorful suits and eccentric, um, dancing (?) are a mainstay of the Chicago River tours, and apparently, Friday mornings on NBC News Channel 5. Also known as “Riveracci,” Vincent stands with his tacky and flamboyant suits on the State Street bridge, twirling and swinging his jacket at the tourists on the boats below. As the documentary admits, if you saw Vincent on the street you’d probably dismiss him as a “crazy,” with his strange suits and odd posture and manner. But beneath the fuschia three-piece, as the documentary shows us, is a relatively normal guy (with a respectable long-term job with Cook County) with acute glaucoma (he’s almost completely blind but usually gets along by himself, hence the observably strange posture and manner) and a desire to be noticed.

The documentary says and does all the right things relating to being yourself, not judging by covers, exposing the hypocrisy of the already-conformed, etc., but what was most interesting to me that the documentary revealed is that beneath the ostentatious goofiness of Vincent’s hobby lies an artist who could be taken relatively seriously. I don’t know how much Vincent could, or would want to, hold forth on the artistic merit of what he does, but his careful attention to detail and aesthetics, his establishment of a routine and a “Vincent” persona, and most of all his photography projects, indicate to me someone with real artistic ambitions. And actually, this strangely enough, connects again to Barfly.

For the Q&A, Vincent came out in a loud three-piece orange suit (with the lapels on the vest) with a blue shirt and did his spin-and-swing-jacket routine to the UI fight song. He and moderator Richard Roeper then swapped jackets for a large portion of the Q&A session. Having fulfilled the Ebertfest quota for “documentary about an eccentric iconoclast,” the guests, Vincent and director Jennifer Burns, were asked the questions you’d expect. How did Burns find Vincent? It turns out that in her day job, she’s a waitress at the restaurant we see him passing by on his way to work. Does Vincent do what he does because he likes attention, or he likes bringing a smile to people’s faces? Both. Is Chicago Sun-Times columnist and documentary interviewee Neil Steinberg an asshole? No. And he’s been Roeper’s friend for twenty years, so watch out, questioner-in-stage-right-seating-section.

4:50 p.m.: Late start after the Victor Q&A, and it turns out we have a surprise short film: Plastic Bag, written and director by two-time Ebertfest guest Rahmin Bahrani (Man Push Cart, Chop Shop). The film is an environmentalist parable, but in an endearingly original and quirky way. It is the story of a plastic bag resting on a pacific beach, who narrates the story of how he left his “creator,” a woman grocery shopper, and has been trying to find her ever since. The voice of the plastic bag? None other than two-time Ebertfest guest Werner Herzog (Invincible, Stroszeck), who met Bahrani at Ebertfest and wanted to work with him. Since Plastic Bag is short, I won’t ruin the plot by summarizing it any further, but it is a witty, sad, and beautifully shot film–so check it out if you have a chance.

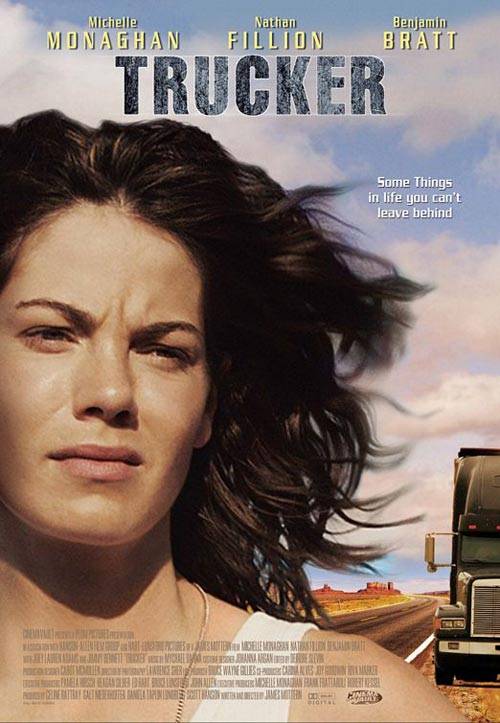

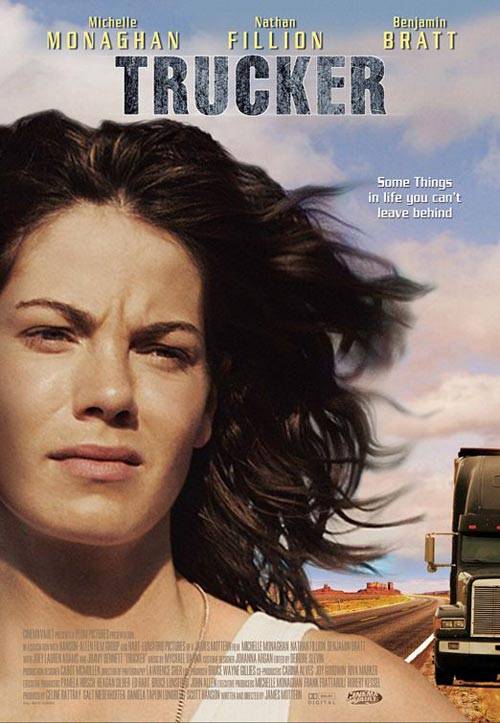

5:30 p.m.: An hour late, Trucker starts. It’s directed by James Mottern, whose name I misspelled in my post about Thursday’s panel discussion. Oops.

If Thursday’s screening of the remarkably well-restored Apocalypse Now was an argument for the beauty and voluptuousness of 35mm that we’re losing with digital, Trucker is the festival’s counter-argument. Trucker is, of course, a very different film from Apocalypse Now, but it was shot and projected beautifully in digital, lacking perhaps the saturation of 35mm but with crispness, a range of colors, and a certain je ne sais quoi (or at least I’m not technically proficient enough to sais quoi) that makes the soft lighting often used in Trucker look wonderful. I’m not abandoning actual film—festival films like Apocalypse Now, Playtime, Lawrence of Arabia, Hamlet, and My Fair Lady have been something else, and unimaginable in digital projection—but Trucker is one of the films that makes me feel not quite so dour about the transition to digital.

If Thursday’s screening of the remarkably well-restored Apocalypse Now was an argument for the beauty and voluptuousness of 35mm that we’re losing with digital, Trucker is the festival’s counter-argument. Trucker is, of course, a very different film from Apocalypse Now, but it was shot and projected beautifully in digital, lacking perhaps the saturation of 35mm but with crispness, a range of colors, and a certain je ne sais quoi (or at least I’m not technically proficient enough to sais quoi) that makes the soft lighting often used in Trucker look wonderful. I’m not abandoning actual film—festival films like Apocalypse Now, Playtime, Lawrence of Arabia, Hamlet, and My Fair Lady have been something else, and unimaginable in digital projection—but Trucker is one of the films that makes me feel not quite so dour about the transition to digital.

As for the content of the film, it was nothing you’ve never heard of before. A long-abandoned child is forced upon a reluctant parent—in this case, a truck driver—because of unforeseen circumstances, and said parent must learn to love the child again. Some important differences are that the parent/truck driver in this case is a woman, Diane (Michelle Monaghan) and the film is just so damn well made. As you know will happen the whole time, Diane learns to accept and love her child and the maternal role she abandoned, but, to embrace another cliche, this film’s about the journey. With wonderful performances all around, especially from Monaghan, Nathan Fillion as Runner, and a very strong script, this was one of the highlights of the festival. It’s a very American independent film, about the nuclear family, the open road, and baseball, but it’s the good kind of uniquely-American film.

7:30 p.m.: Dinner in the Green Room. I don’t eat with anyone terribly important, but still, kudos to Michaels’ Catering for providing me with two very good meals and one decent meal this weekend. (Though I wasn’t impressed with the pork. We’ll talk.)

9:00 p.m.: I’ve managed to already mention Barfly twice in reference to other films. Based on a story by Charles Bukowski, the film is almost purely a character study, and one of the more deft ones I’ve ever seen. Each scene peels back another layer of its main character Henry (Mickey Rourke), to reveal behind his willfully jobless, messy self a serious artist with an honest-to-goodness ethos. The film is framed by fist-fights: in the first scenes, we don’t understand why relatively puny Rourke keeps challenging bartender Frank Stallone to pointless fist fights, but by the time the last scene rolls around and not much has changed at all, we better understand why this character gets himself pummeled night after night.

The film is about staying true to oneself and one’s artistic project, even if that means thoroughly embracing your ugly side, and the ugliness of the world. The film and its character are fiercely against the bourgeois writing establishment, and distrustful of bourgeois literary and moral values. Henry and his newfound love Wanda (Faye Dunaway) brazenly embrace rather the values of alcoholism and perpetual poverty, forming a sort of resistance to the dogged, chronological advancement in the world valued by the film’s one bourgeois character and the “American Dream.” Hence, the film ends exactly where it started: Henry is spending all of his money on alcohol, starting fights for no reason, and writing in the wee hours of the morning when he gets him. Barfly is the ultimate celebration of the defiant, self-ostracized artist.

The most interesting part of the Q&A came when the critics asked director Barbet Schroeder about an “apocryphal” story regarding the production of the film, in which it was suggested that Schroeder threatened to cut off his pinky finger if the production company didn’t come through with some money they promised him. Like Herzog threatening Kinski with a rifle, this is one of those hyperbolic stories about the struggle of filmmaking that is generally considered to be just a story; Schroeder set them straight. In what I think is a pretty accurate paraphrase, “I do not want to tell the whole story because we do not have time here”—a very un-Herzogian response from the French director—“but yes, I had threatened to do this because they had promised something and were not going to . . . I cannot explain the whole thing here, but yes. If I did not do this I would have to sue, and they have lawyers—I told them that my lawyer was a Black&Decker [big audience laugh], and that I would do a press conference holding my pinky finger to tell what they had done. I shot something into my hand, too, so that I would not be able to feel, it would not hurt when I did it.”

11:30 p.m.: The night is more or less over. Miriam and I head to the smaller Saturday after party, the happenings of which are not worth reporting here, except that the food spread is always excellent at the Saturday one, and the open bar has more variety. Friday you get your choice of Stella Artois or cheap red wine; Saturday you get scotch.

And as I’m heading out, I realize there’s just one show left in what is only my second complete—but probably final ever—Ebertfest. I only have a couple months left in my beloved C-U, and this is my favorite local event every year, if only because it’s something like a real event about a thing I love—film—happening in my hometown. I have my criticisms and cynicism about some of the things at Ebertfest, which you may have picked up on, but overall this is the best thing that happens in our community year-to-year. Whatever else it is, it’s also people gathering around to watch a bunch of good movies in a really, really cool old theater, and I think I’m lucky to have had the opportunity to have lived here and have gone to so many shows over the years.

And with that not-particularly-eloquent tribute, I’m out.