Even in an increasingly digital world, we still find ourselves surrounded by physical ephemera. They take many shapes and sizes: concert flyers and programs, coffee shop stickers, course announcements and advertisements, business cards, political campaign signs, and a still impressive variety of newspapers and magazines. These artifacts were not designed to persist. Instead, they were created to serve a purpose and then…fade away. However, were they preserved and able to endure for 50, 100, even 200 years, they’d offer invaluable insights to any scholars and researchers willing to mine them for an authentic glimpse into life in 2018.

Thankfully, there exist capable individuals who see the value in preserving the quotidian and use their talents to conserve for future generations what for many would be fodder for the trash or recycling. Many of these librarians work at the University of Illinois Rare Book & Manuscript Library (RBML) and their craft is on full display in the RBML’s current exhibition, Building a Library: the Cavagna Sangiuliani Collection at Illinois.

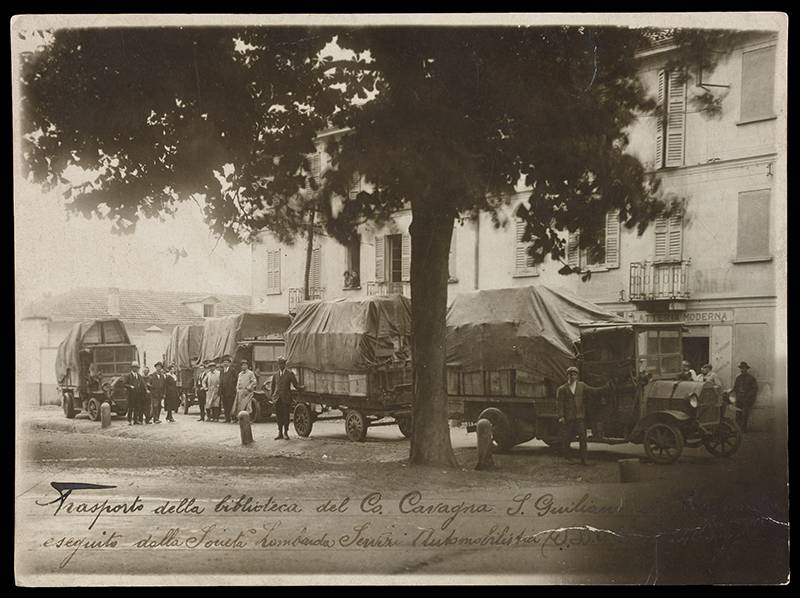

Purchased in 1921, the Cavagna Sangiuliani Collection was acquired by the university to help enhance its status as a leading research institution. Among the collection’s 50,000-plus volumes, there are books on everything from dealing with cholera and the plague to the political and civic histories of the towns and regions of Northern Italy. There is also a varied collection of ephemera in the form of calendars, political announcements and proclamations and government documents, some dating back centuries.

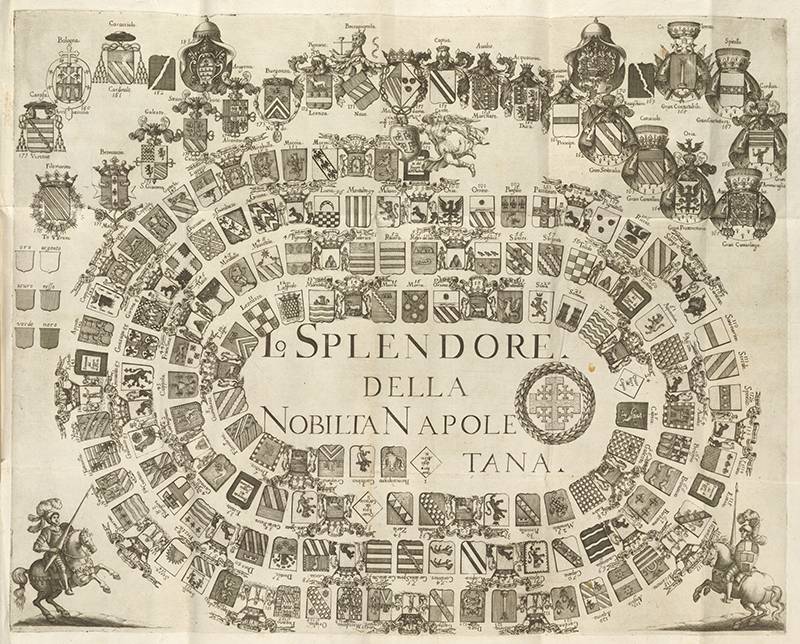

Many of the highlights of the collection (including a board game for aristocrats and a meticulously researched and painstakingly illustrated family tree) are on display as part of the “Building a Library” exhibition showing currently at the RBML’s Ellen and Nirmal Chatterjee Exhibition Gallery. I had the good fortune to speak with the exhibition’s curator, Chloe Ottenhoff, who told me a little about the RBML, the Cavagna Sangiuliani Collection and its origins.

For this collection in particular [the The Cavagna Sangiuliani Collection], about half of it had remained uncatalogued since its initial purchase in 1921 and the grant project was to finish describing and making accessible the rest of the collection.

Smile Politely: How does one get a job like yours?

Smile Politely: How does one get a job like yours?

Chloe Ottenhoff: Right. Well, I earned my MLS here [at Illinois] and I did a couple of practicum projects that operated out of the RBML, for instance a project to digitize maps of Africa before 1900, so that kind of got my foot in the door. In terms of study, I also have a Masters in Art History so that kind of lends itself to understanding the timeframe of a lot of these collections.

SP: So, the reputation of the University of Illinois library precedes itself. It’s huge. It’s one of the biggest library systems in the country. Can you tell us a little about the Rare Book and Manuscript Library (RBML)? Is there anything particularly cool/interesting in the collection?

Ottenhoff: Sure. Within the breadth of special collections libraries, the RBML is one of the largest in the country. We’re also a publically accessible repository so we’re open to anyone to come in and use our collections.

It is a very large collection. We have over 600,000 volumes just in the RMBL and, oh, two miles of archival documents? Yeah, so, it’s really, really large. And we have so many specialities.

SP: Cool! Like what?

Ottenhoff: We have a great Shakespeare collection. We have Milton — we have one of the largest collections of Milton editions in the country. We have a “First Folio”, we have a Gutenberg Bible fragment, we have cuneiform tablets, we have medieval manuscripts. We really have something for everyone.

We also house a lot of literary authors’ papers, notably poets such as Carl Sandburg, W.S. Merwin, and fairly recently, we got the Gwendolyn Brooks literary papers which is really exciting. H.G. Wells is another author who generates a lot of excitement. We have manuscript drafts for “War of the Worlds” and things like that. And it’s all publically accessible.

SP: So, in addition to the “public good” aspect, what role does the RBML play among scholars and researchers?

Ottenhoff: We’re a repository for rare and special materials. That doesn’t mean that they have to be 400 years old for them to be here. But we have a commitment to preserve and retain these materials and within the larger library system, that’s not always the case. We commit to making sure these materials can last for another 100, 200 years, and so that researchers and scholars can have access to them.

We also have a pretty robust digitization program. A lot of it is request driven, so if a patron, say from the UK, or Canada ,or Italy, wants to have access to something in our collection, we will answer their request. Sometimes it’s only one page or a couple pages of a book and sometimes it’s the entire thing.

SP: Very interesting! The current featured exhibition is titled “Building a Library: The Cavagna Sangiuliani Collection at Illinois.” Can you tell us a little about “the Count”?

Ottenhoff: Sure. So, Count Antonio Cavagna Sangiuliani was born in 1843 in Alessandria, Italy. He was from the Lombardy and Piedmont regions of Northern Italy. He was a book collector, obviously, and he was a historian himself. He wrote a lot about the history of the local towns where he was from and where his family was from. He was also a local official and was an active member of his community, serving on a lot of pro-patria associations honoring the history of these local towns.

He was also an avid genealogist. He traced his family back to the 12th century and some of what is in the collection follows that impulse to trace family and local histories back to Roman times, or back as far as onecan, and connecting that with this patriotic feeling for one’s [new, unified] country. He was born in a really turbulent time for Italy. Italy unified in 1861 and before then, there were all these regional city-states and that’s part of the reason why patriotism for one’s region was so important and why this collection is so Northern [Italian] driven. It’s a really complicated history but there are a lot of primary sources that trace those changes.

SP: Why did the university decide to purchase the collection?

Ottenhoff: When it was originally purchased, the collection was meant to be used. During the first couple of decades of the 20th century, the University Library was really trying to build their collections to the point where they could really try to compete as a research institution. It was also to foster research departments. You can’t have a great Classics Department or Romance Languages Department without great professors and researchers, and these people need collections to support their research. And that was the main impetus for buying the collection.

From a historical perspective, it was a convergence of different factors: the University of Illinois was looking to buy books, World War I made it so that maybe local Italian institutions couldn’t afford to purchase private collections, and it was available. And the university got a 50,000-plus volume collection. It was beneficial for all parties and the library substantially increased its holdings with one major purchase.

SP: What all does the collection contain? Is there anything particularly special about the collection? What have you chosen to highlight for the exhibition?

Ottenhoff: Aside from Italian history and law, the collection is really strong in art and architecture and the history of science and medicine. I also wanted the exhibition to showcase other strengths in the collection. There is lot on geology and volcanology and riverbank engineering, things that were really important to Italy throughout its history.

If you take Milan alone, we have documents from the 15th century up until the 20th century that trace from when it was a duchy, to when it was under Austrian control, to Spanish control, to when it was taken over by the French!

Also, the cataloging of the collection was funded by a CLIR grant, now in its final year.

With the grant ending, we wanted to showcase the work that we’ve done and a lot of what’s on display are things that we’ve discovered while cataloging the collection. The hidden gems within the hidden collection.

There is a really rich collection of resources for 19th century, Italian daily life. They call this period “the Risorgimento”, the period of unification and I think there is a wealth of primary source documents for understanding this time. Some of it may seem mundane, like sanitation rules for a tiny, northern Italian town. But, when you think about it, it gives evidence about what the issues of the time were. Things like almanacs that were often thrown away. But those give so much information about what it was like in 1848: what was at the opera, what was going on around town, what ruler was visiting. And those kind of more ephemeral materials don’t often get the attention that the medieval manuscript does. Or the really beautifully engraved architectural work.

I think there is a modest, humble aspect to the collection that gives a really unique perspective to Italy in the 19th century. Aside from that, it also has so many beautiful and amazing works of art and architecture and genealogy, and the exhibit showcases the more illustrative materials in the collection.

SP: The collection will be open to the public until December 14th. Why should people stop by for a visit?

Ottenhoff: We’ve actually decided to keep the exhibit open until the end of the semester. So, we’re definitely going to keep it open until (December) 21st, if not until mid January.

The exhibition is a chance to see some totally unique items. Things that are nowhere else in the world, things that only Illinois has. And I think it’s a chance to see a very large collection distilled into something that you can digest and get a feeling for. In one case alone, you can see a charter on vellum from 1106 issued by the Holy Roman Emperor next to a 19th-century manuscript poem about risotto! How cool is that!? [laughs].

Building a Library: the Cavagna Sangiuliani Collection at Illinois

University of Illinois Rare Book and Manuscript Library

1408 W Gregory, third floor

Urbana

Open till December 21st, free and open to the public

Photos from the University of Illinois Rare Book and Manuscript Library