Last week, U of I’s Department of Landscape Architecture hosted a three-day charrette competition to re-imagine how campus might look over the next 50 years.

Internationally recognized designers and U of I landscape architecture graduate students worked in teams to create design solutions that address anticipated technological and environmental changes over the next few decades. Teams started work on a Sunday evening and presented their ideas on Tuesday afternoon. According to Landscape Architecture Department Head William Sullivan, the fast turnaround and competitive atmosphere of a charrette — an intense period of design planning—is a popular format for solving complex problems in the discipline of landscape architecture.

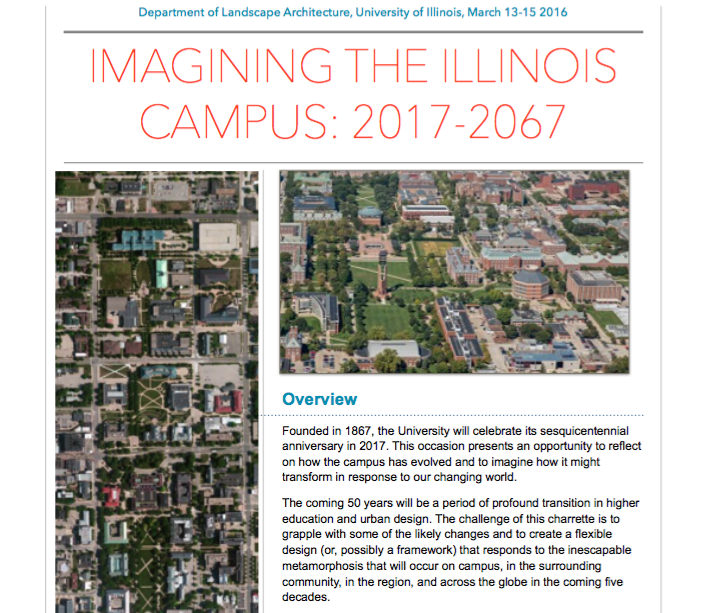

This charrette responded to the U of I’s upcoming sesquicentennial anniversary and what Sullivan said are the enormous and inevitable changes for outdoor spaces in the next 50 years.

“Over the next 50 years,” said Sullivan, “one big change is that we can expect to see autonomously driven vehicles on the roads. These would be cars without wheels that are driven by apps. They would be much safer to drive and also perhaps part of the sharing economy—if that were the case, individual drivers wouldn’t have to park or maintain their vehicles. Those changes in car technology would affect how we think about the design of public spaces. Some designers think that in 30 or 40 years, we may need 95% fewer parking spaces on campuses like U of I than we have right now. That opens up huge possibilities for the campus. We could imagine a campus with no parking garages or surface parking lots. Those spaces could instead be used for buildings and green infrastructure. We could increase biodiversity and have a significantly healthier campus landscape.”

“Over the next 50 years,” said Sullivan, “one big change is that we can expect to see autonomously driven vehicles on the roads. These would be cars without wheels that are driven by apps. They would be much safer to drive and also perhaps part of the sharing economy—if that were the case, individual drivers wouldn’t have to park or maintain their vehicles. Those changes in car technology would affect how we think about the design of public spaces. Some designers think that in 30 or 40 years, we may need 95% fewer parking spaces on campuses like U of I than we have right now. That opens up huge possibilities for the campus. We could imagine a campus with no parking garages or surface parking lots. Those spaces could instead be used for buildings and green infrastructure. We could increase biodiversity and have a significantly healthier campus landscape.”

According to Sullivan, landscape architecture is an interdisciplinary field that designs public spaces for people while taking into account changes in technology as well as environmental concerns.

“Landscape architecture is the discipline that works with natural systems to create healthy and interesting places for people at a variety of scales,” said Sullivan. “We work on everything from parks, campuses, to entire regions—everything from urban design to garden design. That means we span a huge scale. We create outdoor places that design for transportation, social interactions, and commerce. We figure out how water should move through urban areas, we address housing and school designs, and we plan livable and walkable communities. A growing trend in our discipline is to create healthy environments in which people have social experiences. We want to inspire people to be outdoors. At the same time, we work to design spaces that increase the amount biodiversity in an area.”

This interdisciplinary work requires keeping abreast of changes in engineering, applied health sciences, and digital technology. “One of the great privileges of being a faculty member at the U of I is having world-class colleagues,” said Sullivan. “We are constantly learning, and we have great people to learn from.”

At last week’s charrette, designers worked on issues such as how to reclaim the spaces taken up by wide streets and how to transform current parking areas into green infrastructure.

“One team suggested moving Research Park to the north part of campus,” said Sullivan. “They envisioned connecting Research Park, campus, and downtown Champaign with a light rail that would extend from Chicago to St. Louis. That would be a catalyst for development in the area.”

Another team examined how changes to the landscape around the south quad could create a more social space, and several teams considered how to capture and use solar energy on campus.

Design teams from last week’s competition

Sullivan’s own hope is that in 50 years, campus will use rainwater differently.

“We’ve designed our campus around the notion that we have to get rid of rainwater,” said Sullivan. “We even call it ‘stormwater’—when you hear that word, you want to get rid of it. Some of us have been saying that we need to change our language and orientation toward rainwater in this community. It’s a precious resource. As soon as you start conceiving of it in that way, you begin thinking about how to create landscapes that would slow rainwater down and let it permeate into the soil, rather than about how to get rid of it. Slowing rainwater down brings about all sorts of beneficial things: biodiversity, new habitats, and spaces where people might be together and find moments of tranquility and peace.”

Sullivan said he sees new possibilities for rainwater in his campus parking lot every day.

“The parking lot near my office was built in the early 2000s,” he said. “It slopes downward, draining water into pipes in the ground, and takes it away from campus. The water goes into rivers that discharge into the Mississippi and eventually the Gulf of Mexico. So the pollutants from our parking lots end up in the Gulf of Mexico. We can design better than that. We can create a healthy groundwater system here. There would be a huge impact on campus and C-U if we treated rain as a resource and redesigned the way we deal with water.”

Sullivan’s work and the proposals from last week’s charrette will help to set the course for what the U of I campus will look like in future generations.