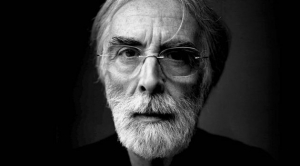

Amour is one of those movies that will leave a lasting impression on its audience, in the same way that love never fades from those who have truly felt it. Amour is directed by acclaimed Austrian director Michael Haneke (pictured at right), most well known for directing disturbing material (like Funny Games or The White Ribbon) that borders on horrific and possibly psychologically damaging. In Amour, Heineke goes a completely, more subtle route.

Amour is one of those movies that will leave a lasting impression on its audience, in the same way that love never fades from those who have truly felt it. Amour is directed by acclaimed Austrian director Michael Haneke (pictured at right), most well known for directing disturbing material (like Funny Games or The White Ribbon) that borders on horrific and possibly psychologically damaging. In Amour, Heineke goes a completely, more subtle route.

Amour focuses on a married couple named Georges (Jean-Louis Trintignant) and Anne (Emmanuelle Riva). They have been married for what seems like over fifty years when, one day, the morning after attending a concert, Anne suffers a stroke. The stroke completely disables the right side of her body, and Georges, knowing his wedding vows as well as he does the Lord’s Prayer, steps in to care for his ailing wife.

Amour focuses on a married couple named Georges (Jean-Louis Trintignant) and Anne (Emmanuelle Riva). They have been married for what seems like over fifty years when, one day, the morning after attending a concert, Anne suffers a stroke. The stroke completely disables the right side of her body, and Georges, knowing his wedding vows as well as he does the Lord’s Prayer, steps in to care for his ailing wife.

What follows after the stroke is something no one wants to see happen to a loved one. Anne becomes weaker, and the audience sees that things will not get better. While it is not for me to say how bad things get, a not-so-subtle clue is provided in the film’s first scenes.

I love Amour as a picture because, on the one hand, it shows the lengths someone will go to be with the love of his life, even if it’s just one small moment at a time. On the other hand, I love Amour because of its unflinching honesty about the pain both halves of the married couple go through. Both Georges and Anne are practical as her health falls into further decay. The film makes no secret how heartbroken Anne is that she is losing the ability to be whom her husband has loved for so long.

Georges has to be the most determined octogenarian I have ever seen put to screen. He is determined to make his wife better; if he can’t make her feel better, then he is determined to make her comfortable. Finally, when he can no longer make her comfortable, he is determined to keep her at home and away from hospitals. After all, she is his and he is hers. The two people are irreversibly linked, not by vows of marriage or their daughter, but by the love they have for each other.

Georges has to be the most determined octogenarian I have ever seen put to screen. He is determined to make his wife better; if he can’t make her feel better, then he is determined to make her comfortable. Finally, when he can no longer make her comfortable, he is determined to keep her at home and away from hospitals. After all, she is his and he is hers. The two people are irreversibly linked, not by vows of marriage or their daughter, but by the love they have for each other.

As much as I would like to say that this film is about commitment, it is not. For me, Amour tells the tale of a great couple’s last moments and how one may never love the same without the other. The beauty of this film is that both people have a distinct and clear knowledge of that fact, and neither of them will let the other know that fact exists.

Despite having such an ugly and depressing tone, Amour has been beautifully shot by Haneke. It is, in many ways, the perfect contrast. There is this great scene where Georges is listening to Anne play the piano because she, like him, was once a musician. He stares at her playing this lovely piece of music and then turns the radio off behind and it’s revealed Anne’s fingers never touched a single note on that piano. That moment speaks to me because that is the point in the film: the audience knows that Georges has lost Anne forever and that he cannot fix what — and who — has been broken.

Amour is a powerful lesson in love. While it doesn’t serve as a guideline for what marriage should be, it reminds us to love as much as we can, for such love is fleeting and can be taken away in a single moment.

The film will continue to play at The Art this week and next. Make plans to see it before it’s gone.

Five out of five stars.