If you were to venture into my mother’s office, you would find three complete bookshelves of biographies and autobiographies. My mom doesn’t read poetry, she doesn’t read novels, she doesn’t read mysteries or even romances. The woman likes life stories, and that’s it.

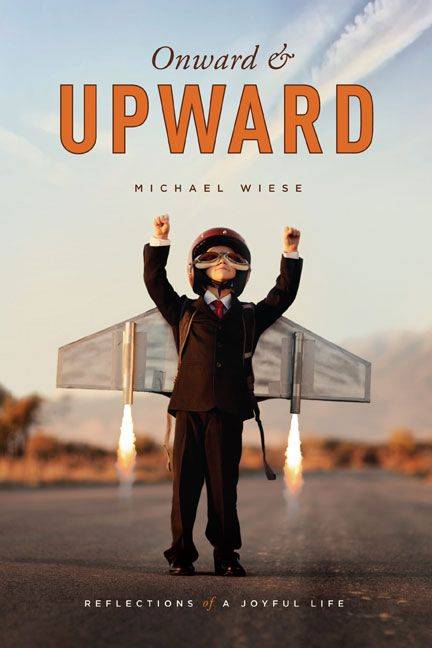

Although I love to read, autobiographies aren’t something I often pick up. I was excited about a change of pace when my editor suggested I review Onward and Upward: Reflections of a Joyful Life by Michael Wiese. Wiese, a Champaign native and film director who traveled to Bali by way of San Francisco and Japan. Wiese’s mother’s maiden name is Kuhn, and her family began and still owns Jos. Kuhn and Company. This premise, certainly, is quite promising; however, right from the start, something was off.

The beginning reads like a more coherent (if less creative) Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. He describes the moment after being born, when “something big carries me and sets me down with a clunk.” You know, something everyone remembers.

The beginning reads like a more coherent (if less creative) Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. He describes the moment after being born, when “something big carries me and sets me down with a clunk.” You know, something everyone remembers.

It becomes clear from the outset that these are not complete narratives: even my sixth-grade students would be able to acknowledge that fact. There is no suspense, no rising action, little conflict, and even less resolution. The book is made up of what could be called vignettes, episodes, sometimes just anecdotes. The beginning is so disjointed that it reads like Twitter updates of Wiese’s life.

There are rare moments of beauty when he touches on universal experiences, such as the quintessential Midwestern activity of catching fireflies in a jar. There are even events that are actually interesting, and it’s a shame that Wiese didn’t weave them together for a richer, more connected story. Everyone’s lives are made up of episodes, and it’s a good writer’s job to connect these events into a coherent, thematic narrative that inspires or at least enriches the reader’s life. This book does none of this.

Another failing of this book is the emotionlessness of the episodes. Some read like a police report: completely objective. One begins to wonder why Wiese even wrote in first person. He is so detached that it’s as though he’s talking about someone else’s life. As the book progresses, Wiese does move from reporting events objectively to providing more insight into his perspective and development as a person. The downside of this is that he doesn’t portray himself as the most likable guy.

For example, he describes Illinois as a “relatively ordinary world.” His consistent dismissal of Illinois — and of Champaign in particular — smacks of snobbery that rubbed me the wrong way. More snobbery occurs as Wiese constantly name drops: Salvador Dalí, Francis Ford Coppola, Jefferson Airplane, Janis Joplin, Shirley MacLaine… even Ketut Liyer, the same Indonesian healer Elizabeth Gilbert befriends in Eat Pray Love. Most of these instances are pointless and extraneous.

For example, he describes Illinois as a “relatively ordinary world.” His consistent dismissal of Illinois — and of Champaign in particular — smacks of snobbery that rubbed me the wrong way. More snobbery occurs as Wiese constantly name drops: Salvador Dalí, Francis Ford Coppola, Jefferson Airplane, Janis Joplin, Shirley MacLaine… even Ketut Liyer, the same Indonesian healer Elizabeth Gilbert befriends in Eat Pray Love. Most of these instances are pointless and extraneous.

He also discusses how he tricked the government into giving him a 4-F rating (“unfit to serve”) as the Vietnam War loomed. Instead of serving in Vietnam, he travels for years throughout Asia, plays music, finds a model girlfriend, and rubs elbows with directors. I cannot blame him for avoiding Vietnam, but Wiese’s cavalier attitude about it and then describing, in detail, his transcendent Asian experiences, seems disrespectful to the people who served in the war.

There are inconsistencies in Weise’s logic as well. When discussing an experience called “getting it” during mediation, he says, “it’s a nonverbal experience that cannot be described in language.” Immediately following that statement, Wiese writes, “For me, ‘getting it’ is simply being aware moment by moment and experiencing yourself as co-creator of your own experience.” What? Didn’t he just say it couldn’t be described?

The nonsense also occurs when he quotes Carl Jung: “It’s not what happened to me; I am who I choose to become.” What?? Why did he write a book that chronicles everything that happened in his life if he believes that he just chose who he wanted to become? It’s these kind of statements that alienate the reader from enjoying learning about Wiese’s life.

The nonsense also occurs when he quotes Carl Jung: “It’s not what happened to me; I am who I choose to become.” What?? Why did he write a book that chronicles everything that happened in his life if he believes that he just chose who he wanted to become? It’s these kind of statements that alienate the reader from enjoying learning about Wiese’s life.

By my mom’s definition, an autobiography starts at the beginning of a person’s life and chronicles its up and downs. I guess that’s what seemed off to me. Wiese has a lot of, “Gee, look how great my life is! I am so lucky!” but not a lot of conflict. He at least has the grace to say how thankful he is, but it doesn’t make for a very compelling autobiography.

When I asked my mom why she likes autobiographies, she said “They’re not fiction. I like to learn about people and their lives.” If you agree, then Onward and Upward would be a great book for you. Wiese provides a look into both a time period (late 1960s San Francisco) and a field (the movie industry) that readers might find interesting. The book’s disjointedness and his detached narration, however, were just too distracting to make it enjoyable to me.