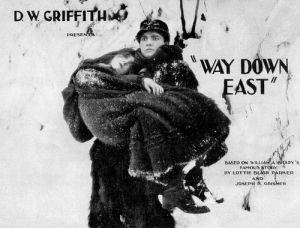

In the unlikely event that a crazed film fanatic backs me into an alley at gunpoint and demands — in order to save my life — that I name the greatest scene the silent cinema ever created, I believe I would survive. With no hesitation, I would name the ice floe scene Lillian Gish endured in D. W. Griffith’s Way Down East, his 1920 classic melodrama with feminist overtones. To this day, few directors, even with special effects, could make an audience gasp as that scene does.

I first saw Way Down East on a summer sojourn to New York City at the Carnegie Hall Cinema. A very appreciative audience was treated to the superlative Museum of Modern Art print with a dubbed musical score. During the moments when Lillian Gish seemed to be headed down that river on an ice floe towards a waterfall, you could feel the audience growing tense. When Richard Barthelmess seemingly rescues her from certain death at the edge of the waterfall, a full house of adult New Yorkers cheered loudly and unashamedly. We were rooting for Ms. Gish to be rescued, and Griffith’s masterful manipulation of our emotions made us wear our hearts on our sleeves for that moment.

Multiple viewings of different Way Down East prints clearly demonstrate the problems of a film in the public domain. Various 16mm and video editions have differing details in the back story and their print quality varies, but no release has dared to tamper with those nail-biting moments near the end when Ms. Gish is tossed out of her workplace in a snowstorm. As the scene progresses, she wanders down to the river and falls onto an ice floe headed for a waterfall, only to be rescued by the man who loves her at the last second. That is sacred footage.

Multiple viewings of different Way Down East prints clearly demonstrate the problems of a film in the public domain. Various 16mm and video editions have differing details in the back story and their print quality varies, but no release has dared to tamper with those nail-biting moments near the end when Ms. Gish is tossed out of her workplace in a snowstorm. As the scene progresses, she wanders down to the river and falls onto an ice floe headed for a waterfall, only to be rescued by the man who loves her at the last second. That is sacred footage.

In the late 1970s, when Lillian Gish was still touring and doing film preservation promotions with restored prints of her films, I drove to the Chicago Theater to be in that audience. Although in her 80s, she was a dynamic speaker, an outspoken advocate of film preservation, and a perpetuator of some Griffith mythology that she was personally part of. She opened her program with (you guessed it) the ice floe scene from Way Down East. Then she proceeded to repeat what was in her autobiography, The Movies, Mr. Griffith, and Me.

Griffith (in his stories and brief autobiography) and Gish both insisted that there were no stunt doubles or special effects. They insisted the temperatures were so cold the cameras had to heated, there were multiple takes, and Ms. Gish got way too close to the nearby waterfall, making her rescue all too realistic. OK, much of that is true. But, later film historians would modify that near-death rescue story a lot.

Here is Ms. Gish’s version from her autobiography, written almost 50 years after the event:

“The scene of Anna’s rescue from the falls was all too realistically re-created. Mr. Griffith was directing Dick (Richard Barthelmess) from a bridge over the river, but the noise from the waterfall drowned out his directions. As I headed for the falls on my slab of ice, Mr. Griffith shouted to Dick that he was moving too slowly, but Dick couldn’t hear him. As Dick ran toward me he became excited, leaped and landed on a small piece of ice that was too small. He sank into the water, climbed back out, finally lifted me in his arms as I was about to go over and ran like mad to the shore.”

Ms. Gish then adds a postscript:

“Years later when Dick and I were reminiscing, he said: ‘I wonder why we went through with it. We could have been killed. There isn’t enough money in the world to pay me to do that again.’ But, we weren’t doing it for the money.”

So the accepted story went, and yet look carefully at that seat-gripping climax at the edge of the waterfall. It is shot in close-up; you do not see the waterfall. There is no sign of ice on the river other than a few suspiciously looking floes near that elusive waterfall. Perhaps the work of Griffith’s superb editors, James and Rose Smith, was even better than we thought? Enter the film scholarship of the 1970s and 1980s.

Two books within a decade would shed much light on that famous scene. Edward Wagenknecht and Anthony Slide’s The Films of D. W. Griffith (1975) states that the waterfall shown in the film was an edited image of the US falls at Niagara, and the rescue was done that summer at a mill race in Farmington, Connecticut—where the ice floes were actually painted plywood attached to piano wires. This book hit that stands while Lillian Gish was promoting her version, which, again, implied she actually was rescued from a nasty spill over a waterfall. Even more amazing—Lillian Gish wrote the introduction to The Films of D. W. Griffith!

Two books within a decade would shed much light on that famous scene. Edward Wagenknecht and Anthony Slide’s The Films of D. W. Griffith (1975) states that the waterfall shown in the film was an edited image of the US falls at Niagara, and the rescue was done that summer at a mill race in Farmington, Connecticut—where the ice floes were actually painted plywood attached to piano wires. This book hit that stands while Lillian Gish was promoting her version, which, again, implied she actually was rescued from a nasty spill over a waterfall. Even more amazing—Lillian Gish wrote the introduction to The Films of D. W. Griffith!

In 1984, Richard Schickel’s D. W. Griffith, an American Life, made many of the same clarifications, even noting that the second unit stayed behind to get additional footage for editing, using doubles. Now, this is a book Lillian Gish loathed. In a 1984 letter she wrote to me, she said, “Mr. Schickel writes about a man I never knew.”

I think one could take issue with Schickel’s description of some of Griffith’s personal characteristics, but his facts on filming have not been disputed by film historians. He confirms the dual locations of Vermont’s White river in winter (for the ice floes) and the summer shoot in Farmington, Connecticut (for the rescue at the waterfall). All sources note that the Farmington “falls” were a modest drop of a few feet over a mill race, but such a fall was still dangerous. Even with plywood floats tied with piano wire, getting Ms. Gish to shore in Barthelmess’ raccoon coat was both a chore and a necessary task. No one disputes the bitter winter weather along Vermont’s White River, the need to dynamite the river the get ice flowing, the multiple takes, the inadequate winter clothing Ms. Gish wore for effect, the necessity to heat the cameras, or the problem of using real ice flows for cinematic impact.

For so long, I wanted to see what was there myself and who had it right; so, in May of 2014, I traveled to White River Junction, Vermont. It is an unincorporated municipality of just over two thousand people on the White River, with an historic downtown that includes the Coolidge Hotel, where Griffith’s film crew stayed. In 1920, the hotel was known as the Junction House. My first stop was the White River Welcome Center, where I met Peter Hughes. Before he opened his laptop and started researching, he had only the vaguest memory of that famous scene and its nearby association. He asked for a few minutes to look into it further and instructed me to the enjoy historic downtown White River Junction and check back.

Peter was good for his word. He knew the local sources to check, and a location was soon identified at the nearby village of Hartford: a highway bridge over the White River. That spot appeared to be the epicenter of the many takes (Gish claimed over twenty takes a day for three weeks), and the river has essentially the same character today as it did in 1920. There are nice rapids, but no waterfall. The waterfall is, in fact, an insert of Niagara Falls, and a real mill race on the Farmington river in Farmington, Connecticut. In other words, some of the glory of that amazing scene belongs to the film editors.

Peter’s directions were spot on as he escorted me to the nearby Hartford location by the highway bridge. I spent a marvelous late afternoon at that location I had experienced so often through the lens of Billy Bitzer and the direction of D. W. Griffith. The day was warm and sunny, and the glorious ghosts of one the silent cinema’s greatest moments seemed ubiquitous that afternoon of discovery.

Coda: After one take Lillian Gish endured in a real snow storm, Griffith noticed her face was covered with spikes of ice and frost. Griffith yelled at Bitzer, “Get that face!” Bitzer yelled back, “I will, if the oil doesn’t freeze in the camera!”

Yes, sometimes, the legend is history.