“Illinois has always stood for the respect and dignity of all people and thought. We are the home of the widest interpretation of free speech and expression. We are the home of spirited debate along the confines of respect and civility. But we do not tolerate acts of intimidation, violence or hate and what threatens one member of our community threatens all of us.” —Richard Herman & C. Renée Romano, from the 2009-2010 University of Illinois Student Code

“Illinois has always stood for the respect and dignity of all people and thought. We are the home of the widest interpretation of free speech and expression. We are the home of spirited debate along the confines of respect and civility. But we do not tolerate acts of intimidation, violence or hate and what threatens one member of our community threatens all of us.” —Richard Herman & C. Renée Romano, from the 2009-2010 University of Illinois Student Code

The UI Student Code covers a lot, from chalking (using water-soluble chalk on sidewalks only) to whom will have first priority for use of meeting space at Beckman (institute researchers). Student Discipline deals with some of the most serious offenses. To name a few: sexual misconduct, stalking, and “the use of force or violence, actual or threatened.”

According to the Office of Student Conflict Resolution, “The purpose of the student disciplinary system at Illinois is to address violations of the Student Code and to shape the behavior of students to be consistent with community standards. The purpose is not punishment.”

Brian Farber, Associate Dean for the Office of Conflict Resolution (dubbed “The Mean Dean” by his colleagues for his disciplinary function), elaborated on this purpose: “Many of the incidents that come to our office involve some very poor decision making—it’s generally not evil people who are out doing evil deeds. And so we don’t have the desire to punish people for the mistakes they make, but instead hope that they can learn from them.”

The point is not to be merely punitive, Farber said, but rather to get the student involved in a program that will “effect change in that person’s life.”

While the purpose of the Office of Conflict Resolution may not be punishment, students who show up there are often facing harsh consequences elsewhere. Dean Farber explained, “Most of the reports that come to our office have already been addressed by the University Police Department or the local police agencies. There are at times criminal penalties that have already been resolved or are pending.”

For violations of the student code, the University imposes two types of sanctions: educational and formal. Students often end up facing both types of sanctions. A formal sanction might be conduct probation, for instance, or—in extreme cases—dismissal from the university. There are a number of educational sanctions, including community service; another example is e-CHUG, which is “an interactive web survey that allows college and university students to enter information about their drinking patterns and receive feedback about their use of alcohol” and is assigned for alcohol-related incidents.

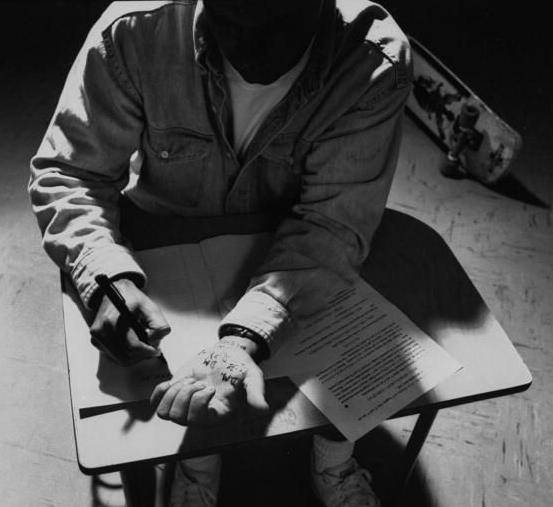

An educational sanction often required by the UI for students accused of violations of the Student Code that were violent or that could have been violent is the Alternatives Program. Students that end up in Alternatives have often committed very serious offenses—threats of violence, harassment, assault, domestic abuse, etc. Alternatives is a 12 week series of classes. It is not run by the University; rather, it is contracted out to the local for-profit agency Cognition Works. Students have to pay a $100.00 fee, and the rest of the cost is picked up by the University. Classes meet once a week for an hour and a half. There are always at least two groups going a semester, and there tend to be around 8-12 students per class.

Cognition Works is a counseling agency located in Urbana offering a wide range of programs including ones on workplace violence and domestic abuse. Behind many of them lies the following philosophy on bad behavior as stated on the group’s website: “At one end of a broad spectrum of these kinds of behaviors you’ll find things like road rage, ignoring deadlines, bullying, harassment, and gossip. At the other end of the spectrum are behaviors such as stealing, assault, and substance abuse. While the effect of these behaviors may be mild or severe, we use a common approach based on proven research.”

Basically, in the Alternatives Program, Cognition Works sees the same “maladaptive thinking patterns” behind missed deadlines and gossiping as they do behind harassment and assault, and they seek to help their students identify and correct these patterns before they lead to even more trouble, even if the student is just there for cheating on a test. Basically, it’s the idea of an ounce of prevention being worth a pound of cure.

Co-owner Debbie Nelson explained, “Because it’s cognitive behavioral work that we do, it revolves around the notion that our thinking drives our behaviors, and because of that process it also drives consequences in our lives.”

She admitted that not every student gets it. However, such uncooperative individuals are “offered the same opportunities and given the same respect” as those that do.

Some of the maladaptive thinking patterns that the Alternatives Program examines are: “Inappropriate Expectations” (maybe thinking that the police will overlook your drunk driving because you had a good reason to be celebrating) “Compartmentalized Thinking” (maybe complaining that you didn’t hit your girlfriend all that hard the time you got arrested for it even though there have been plenty of other incidents in the past), and “Specialness”.

Class topics during the 1.5 hour sessions include Choice and Accountability, Abuse and Violence, and Conflict Resolution Skills Such as “I” Language. (“I” Language is the concept of not blaming the person you’re angry at—instead of saying “You’re annoying,” you say, “I’m annoyed.”)

Nelson also promotes the concept that Alternatives isn’t so much a punishment as an opportunity, although the students assigned to it rarely see it that way at first: “If they’re intent on graduating from the University of Illinois, this is the time for them to look at what their choices have been. So, we’ve go their attention, but when someone is being punished they’re not that open about someone giving them feedback or information about what they have chosen. They have an opportunity to see what some of the thinking patterns are that have brought them this far in their lives. Some are helpful and are working out just fine; others aren’t so helpful and are leading to trouble.”

Alternatives instructors have come from a variety of backgrounds. Nelson said that she’s looking for people who believe in the philosophy first, rather than any specific degree. Instructor Caleb Curtiss (also Smile Politely editor), came to his job with Alternatives from (among other things) having participated both as a teen and adult in Operation Snowball, an Illinois-based youth peer-led prevention program, and from having worked with substance abusers at Prairie Center.

For Curtiss, the program is largely about holding students accountable for their actions and said that, “I think that a lot of these young people are being held accountable for the first time in their lives, and they’re not used to having someone press the point with them.”

Curtiss said that for him, holding someone “accountable” essentially means that, “We ask them to take responsibility for whatever it is they did. We’ve had people in there for threatening someone with a weapon; we’ve had someone in there for cheating on a test. They’re all held accountable. We hold them accountable for the thinking patterns behind their choices. We’re looking at them as individuals, but no one gets “lighter” treatment because of it.”

Curtiss admitted that the students rarely want to be there in the first place, and while physically present, frequently start off Alternatives just going through the motions. To fight this, instructors, in his words, “give our clients the chance to focus on their thinking by holding them accountable for specific behaviors.” For instance, if a student’s cell phone ringing in class becomes too much of a pattern, he or she can be dismissed from the whole program.

However reluctant his students may be at the beginning, though, Curtiss believes that, on the whole, people get with the program in a spirit of cooperation rather than coercion: “Very rarely do we have clients coming in that are enthusiastic about being there. But by the end of the twelve week period, most of them—while they haven’t been happy to have been giving up their Tuesday evenings—see value in having come.”