“There is no such thing as clean coal … coal at the very least has blood on it.” — Steve Earle

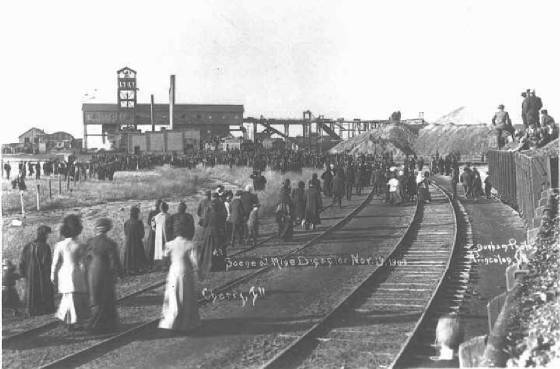

Cherry, Illinois. Nov. 13, 1909

The seventh rescue trip into the coalmine revealed the enormity of the horror. Confusion over bell signals from the 12 rescuers in the cage below led the engineer at the hoist to maintain protocol and not act until he got a proper signal. The seething crowd of miners’ wives and relatives demanded he hoist the cage. Fearing for his life (he later left town in a hurry), he raised the cage.

The clothes were still blazing on the 12 charred bodies; Children fled, crying in terror. Women and men screamed, vomited, fainted, and then, worse, realized that there was no escape for the hundreds of their men and boys in the mine; the fire was in the shaft. The company moved to seal the mine to starve the fire of oxygen; the families said it only cared about protecting the coal veins and not saving miners. The state militia was brought in to maintain order, and firefighters and water from Chicago arrived to try to put out the fire. News of the disaster flew around the world, and relief donations poured in.

It’s estimated 259 persons died that day in Cherry, a company town on the flat prairie just north of the Illinois River Valley. It’s the worst mining disaster in Illinois history, the third worst nationally. And there was no way it could have happened; it was a state-of-the-art mine and was deemed fireproof by the mining experts who said, as experts do, “trust us.”

Cherry, while the deadliest, was only one of 20 mining disasters in Illinois that year. King Coal fueled the entire American economy, and loss of life was part of the cost of doing business. Cherry, which didn’t exist five years earlier, was one of many towns that sprung up around coal mines in the Braidwood fields, around Danville, then along the Illinois River Valley, in Christian and Sangamon counties, and then the entire Southern Illinois coal belt. Illinois had, and has, an enormous amount of coal under all that flatland.

The Milwaukee Road railroad dug the mine and built Cherry to supply coal to its locomotives. It was a model coal mining community. The office building where miners signed in and drew their pay was painted Milwaukee Road orange; adequate grey-painted houses (the photo at left shows a row of 20 miners’ houses in Cherry in 1920) and services were provided, and the mine was supposedly safe. The promise of year-round, steady employment drew miners from around the U.S. and the world, particularly from Italy and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. When the mine opened in 1906, 2000 people lived in Cherry.

The Milwaukee Road railroad dug the mine and built Cherry to supply coal to its locomotives. It was a model coal mining community. The office building where miners signed in and drew their pay was painted Milwaukee Road orange; adequate grey-painted houses (the photo at left shows a row of 20 miners’ houses in Cherry in 1920) and services were provided, and the mine was supposedly safe. The promise of year-round, steady employment drew miners from around the U.S. and the world, particularly from Italy and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. When the mine opened in 1906, 2000 people lived in Cherry.

What went wrong? This mine had electric lights, was well ventilated and well timbered. The flaw was not in the technology per se. It was in the need to maintain continuous extraction, both for the company and for the workers. There was no other source of income for these families, and the company had marginal operating costs to consider. It was about economics.

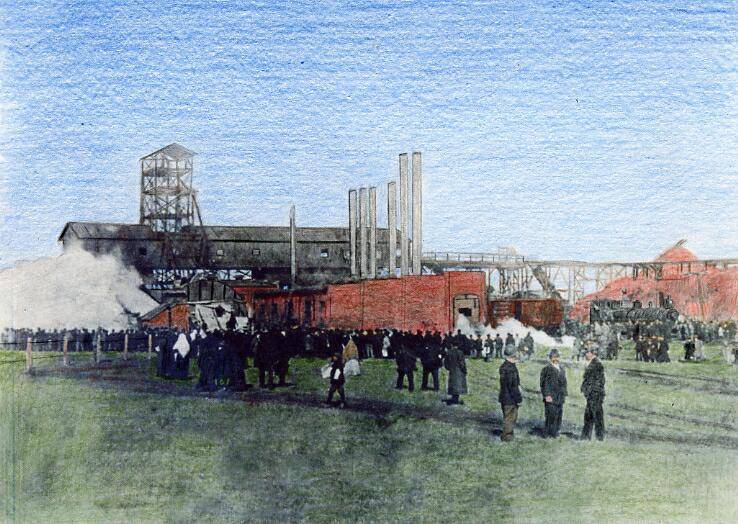

The electrical system had shorted, so to maintain production, the mine was lit by the old method of kerosene torches. A cart of hay for the mule stable below was accidentally ignited, and then a series of bad decisions by miners, supervisors and mine operators, as well as bad communications, resulted in the fire going out of control and trapping more than half of the workers who went in that morning. (The colorized photo below shows smoke billowing from the mine after the huge ventilation fan was reversed to draw smoke out, but which unfortunately drew the fire into a shaft, which then destroyed the fan — a major mistake.)

The Cherry Mine Disaster was a hundred years ago this November, so it’s ancient history and it’s time to move on, as those who would conceal the past to protect their future interests (usually politicians, pundits, and that ilk) say. The Cherry mine disaster is just another fading episode in the remorseless passing of history.

The color of our place in the world this time of year tends toward dull brown and various shades of gray; driving anywhere on the Grand Prairie is even more monotonous than usual. It’s not only in the denuded monoculture landscape, but in the monoculture of where you stop to get gas or food. But there are oases one senses while listlessly rolling through the monochrome. Strange features emerge: abandoned buildings, enormous brick smokestacks unattached to any building, large forested mounds in the middle of flat fields, round-roofed buildings that house antique malls but once were dance halls. Dissolution gives way to wondering about these traces on the landscape and the cultures that built them.

Cherry is still there, but only a quarter of its population in 1909. Miners’ cabins have been remodeled into nicer home. The mine closed for good 70 years ago, and locals commute into larger towns like LaSalle and Peru for work. Still, taverns in the area serve Bagna Cauda, a garlicky dipping sauce brought to the region by miners’ families from the Piedmonte region of Italy. The mine buildings have been recently razed, but the spoils pile, built by boys pulling shale, rocks and dirt from the coal, remains as one of those strange landscape features (left). And the coal is still there.

Cherry is still there, but only a quarter of its population in 1909. Miners’ cabins have been remodeled into nicer home. The mine closed for good 70 years ago, and locals commute into larger towns like LaSalle and Peru for work. Still, taverns in the area serve Bagna Cauda, a garlicky dipping sauce brought to the region by miners’ families from the Piedmonte region of Italy. The mine buildings have been recently razed, but the spoils pile, built by boys pulling shale, rocks and dirt from the coal, remains as one of those strange landscape features (left). And the coal is still there.

We may not remember the Cherry Mine Disaster, but it was the spark that led to Illinois’ first workman’s compensation law. The arguments over that contain ghostly echoes of the arguments over health care today.

Proponents noted that nowhere else in the civilized industrial world was there no workman’s compensation system. The American system was one of personal injury litigation, something that poorly served all the workers’ families who could not understand English, and were illiterate in their native tongues. Besides that, as a 1912 government commission on industrial relations reported, the combination of rigged judicial systems, company towns, and bought-off legislatures meant that laws to protect workers were routinely ignored.

Still, change for the better in working conditions has come, although it’s hardly perfect for all (think migrant agricultural workers), and is still under attack by vested interests (get them damned gummit OSHA bureaucrats off my back). The age of coal was gradually replaced by the age of petroleum, although coal still provides half of our electricity (and that seems unlikely to change much in the near future). As the age of petroleum begins its descent, another echo from the coal age reverberates. Nearly every notice or writing about a coal mine in that era refers to an “inexhaustible supply.” Some more temperate writers said “almost inexhaustible supply.” Today we hear about 200 year supplies of coal in the US. And Illinois touts the third-largest deposits in the country after Wyoming and Montana (yes, more than Kentucky and West Virginia), some 200 billion tons.

Still, change for the better in working conditions has come, although it’s hardly perfect for all (think migrant agricultural workers), and is still under attack by vested interests (get them damned gummit OSHA bureaucrats off my back). The age of coal was gradually replaced by the age of petroleum, although coal still provides half of our electricity (and that seems unlikely to change much in the near future). As the age of petroleum begins its descent, another echo from the coal age reverberates. Nearly every notice or writing about a coal mine in that era refers to an “inexhaustible supply.” Some more temperate writers said “almost inexhaustible supply.” Today we hear about 200 year supplies of coal in the US. And Illinois touts the third-largest deposits in the country after Wyoming and Montana (yes, more than Kentucky and West Virginia), some 200 billion tons.

Coal mining in Illinois was pretty much shut down by the Clean Air Act. While our coal has a very high heat value, it contains a lot of sulfur (and other nasty substances), so it’s been replaced by low-sulfur, lower-heat-value western coal. But new technologies that promise near-emissionless combustion are rapidly renewing interest in Illinois coal. Coal mining regions in the state are hungry for that economic development, although mining jobs for today’s Hunkies and Eyetalians will never be what they once were; mining has become highly mechanized and robotic.

The big coal story around here of course is the planned multi-billion dollar federally and utility funded FutureGen plant in Mattoon, which promises to unleash our coal resources by sequestering combustion carbon dioxide (the global warming gas) underground. Local pols and editorialists are naturally drooling over it, but it might just be an enormous boondoggle or simply a vast misappropriation of resources.

Whatever the results, it’s almost certain that coal mining is going to increase around here. And that’s going to lead to internecine conflict like that now going on in West Virginia.

Of course this will have nothing in common with the days of Cherry. Technology, safety, regulations, are so much better now… there will be none of the shenanigans detailed in the 1912 report from the Commission on Industrial Relations. Although the threat today is not so much to the workers as to the environment, given the political environment in Illinois these days, or any days, you can be sure the environment will be protected above all else. Trust us.

One wonders what the traces on the landscape will be in 2109.