The beats echo off the tile floors of the Cordão de Ouro Capoeira Academy in Champaign, where six students pound djembe drums in unison under the watchful eye of instructor Bolokada Conde. A native of Guinea, West Africa, Bolokada is dressed almost entirely in black, wearing jeans, sneakers, and what looks like a traditional African shirt with white fringe. The late afternoon sun shines through the windows of the spacious acedemy. In many ways, the room appears closer to a karate studio than a musical space: the floor plan is open, a water cooler stands in the corner, and the room’s support column is heavily padded. Long sticks that look like weapons hang from the walls; but they are actually musical instruments used in Capoira, a Brazilian activity that combines martial arts, music, and dance.

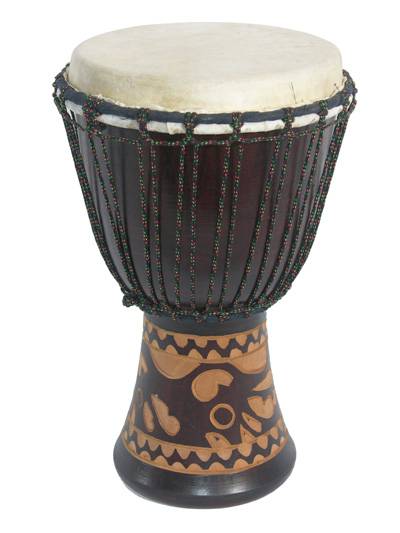

It is my second time participating in Bolokada’s workshop. Replicating his style and sense of rhythm is an overwhelming task for a beginner. Bolokada plays a pattern of beats, and the students attempt to duplicate it. The djembe (pictured, right) is a melodic instrument as well as a percussive one. You get different tones depending on an endless array of techniques, including where you strike the drumhead with your hand, how hard you hit it, and the flatness and rigidity of your palm. It is a difficult instrument to control. I attempt to follow along with the others, but the beat gets trickier, and I have to drop out and listen to regain my bearings before tentatively rejoining the exercise.

It is my second time participating in Bolokada’s workshop. Replicating his style and sense of rhythm is an overwhelming task for a beginner. Bolokada plays a pattern of beats, and the students attempt to duplicate it. The djembe (pictured, right) is a melodic instrument as well as a percussive one. You get different tones depending on an endless array of techniques, including where you strike the drumhead with your hand, how hard you hit it, and the flatness and rigidity of your palm. It is a difficult instrument to control. I attempt to follow along with the others, but the beat gets trickier, and I have to drop out and listen to regain my bearings before tentatively rejoining the exercise.

The students clearly take their practice seriously. Many bring their own drums and discuss practicing on their own. Yet the vibe is welcoming to a novice like me. Students nod with encouragement as I progress through the exercises.

Bolokada halts the group and asks each person to play alone. Now, he offers an individual critique, placing his own hands on the djembe to demonstrate the proper technique. There’s a right way to do this; it’s not a free-form deal. As he communicates this point to us, he flashes an easy smile. To help us understand the sounds we are attempting to coerce from our djembe, he speaks each sound phonetically. His voice is relaxed and he speaks softly, with a slight accent. His laid-back manner belies the force he frequently displays on the drums.

When he gets to me, I falter. I just can’t produce the SLAP sound that he and the more advanced students strike on their drums. When Bolokada strikes the drum, it resonates like a firecracker going off. After several attempts, my SLAP improves somewhat, and Bolokada moves on to the next pupil.

THE MASTER

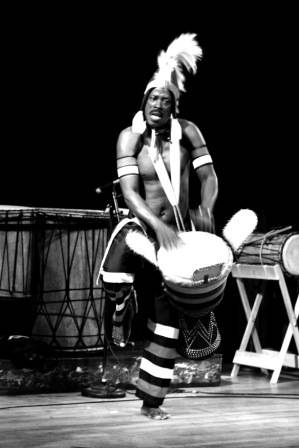

Bolokada (pictured, right) is called a djembefola, or master drummer. It is the highest honorific that can be given to an African drummer, a title bestowed to a musician who is known by other masters to have reached the highest level of the art form. Such a performer is versed in the rhythms of not only his own ethnic group, but that of neighboring groups as well. He knows the ceremonial songs and dances that accompany each rhythm.

Bolokada (pictured, right) is called a djembefola, or master drummer. It is the highest honorific that can be given to an African drummer, a title bestowed to a musician who is known by other masters to have reached the highest level of the art form. Such a performer is versed in the rhythms of not only his own ethnic group, but that of neighboring groups as well. He knows the ceremonial songs and dances that accompany each rhythm.

Bolokada cannot remember when he began to play the djembe: “My mom tells me I was two,” he tells me. It was obvious from an early age that he was exceptionally gifted on the drum. He began to play at local celebrations, and attracted the attention of a village mayor who put him in touch with Les Percussions de Guinee, a prestigious music and dance ensemble which focuses on West African traditional music. Bolokada eventually became the group’s lead drummer, then toured the world with the group.

“I have traveled to a lot of countries,” he says. “I have seen the world. It is because of the djembe.”

One of his djembe students helped him make the trek to America. Since 2004, he has been teaching and performing in the United States, where he has worked with Ballet Waraba in North Carolina, Ballet Wassa-Wassa in Santa Cruz, California, and Les Perscussion Malinke in the San Francisco Bay area.

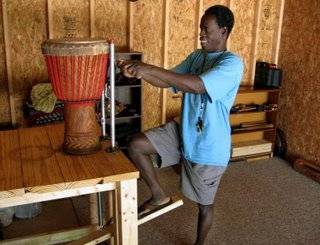

Bolokada is currently a visiting lecturer at the Center for World Music at the University of Illioins. In addition to his drumming workshops, he offers private lessons and repairs and sells djembes (pictured, right). He remains an active performer, too. He plays Zimbabwean music with local group Mhondoro, and he recently performed at the Krannert Center with other West African percussionists as part of the Mande Drumming Ensemble, which consists of Bolokada’s students at the Center for World Music.

Bolokada is currently a visiting lecturer at the Center for World Music at the University of Illioins. In addition to his drumming workshops, he offers private lessons and repairs and sells djembes (pictured, right). He remains an active performer, too. He plays Zimbabwean music with local group Mhondoro, and he recently performed at the Krannert Center with other West African percussionists as part of the Mande Drumming Ensemble, which consists of Bolokada’s students at the Center for World Music.

“My university students learn very fast,” he says. “Everybody learns differently. Some fast, some slow, some strong, some weak. But I like to see people learn.”

He also likes living in central Illinois, noting that he has many friends here. But, unsurprisingly, he does not care for the winter weather. It is much warmer in his native Guinea, and he is planning a return there for a drum and dance tour.

A PARTICIPATORY EXPERIENCE

After an hour or so, the djembes are set aside and a few of the students move on to play the dundun (or dunun), a larger drum played with sticks that features a sort of cowbell on top (pictured, right). A trio of students play separate but interlocking rhythms that create an intricate wall of sound — a thrilling example of the whole being greater than the parts.

After an hour or so, the djembes are set aside and a few of the students move on to play the dundun (or dunun), a larger drum played with sticks that features a sort of cowbell on top (pictured, right). A trio of students play separate but interlocking rhythms that create an intricate wall of sound — a thrilling example of the whole being greater than the parts.

Students bring different levels of involvement to the workshops. Local percussionist Chad Dunn videotapes each lesson for later study. Ken Salo, a lecturer at the university, approaches each lesson more casually. He’s been attending Bolokada’s workshops, off and on, for the past year. He enjoys playing as a means to connect with others.

“Drum Circles are a way of making community,” Salo says, “people doing the same stuff at the same time.”

I can see why Salo and Dunn are enthused by the workshops. When everyone is playing together, you feel part of a powerful beast; it’s a sensation both intricate and primal. At my first meeting, the group played a relatively simple rhythm together while individuals took turns soloing over it. There was a tremendous variety in the skill of the solos, ranging from novices like me to masters like Bolokada, by all accounts one of the best djembe players in the world. However, even as a beginner I found it possible to contribute to the group. It’s this accessibility to the music form that makes these workshops unique. In short, I get to contribute in some small way to world class World music.

The class ends in a casual wind down. Although participants are paying for each workshop, Bolokada is not punching a clock. He lingers to chat with each of us and provide pointers. He approaches me as I bang away on the djembe and further demonstrates how to get the distinctive SLAP sound that has eluded me so far. I finally realize that the key is striking forward on the drum, not backward as I had been doing. It is a gratifying moment for a novice, but child’s play for the master.

——

Bolokada’s workshops run on Sundays through May 31. They are from 4:00 p.m. to 5:30 p.m. at Cordão de Ouro Capoeira Academy, 32 E. Springfield Ave., Champaign. The cost is $12 to $15 per person. Drums are provided.

Bolokada performs tonight, Feb. 20, at the Cowboy Monkey with Mhondoro under the name “Mhondoro Meets Bolokada.” His performance begins at 9:30 p.m., and the cover is $10. Headlining the concert is Toubab Krewe.

If you enjoyed this article, Smile Politely also recommends:

+ Foreigner music: the sounds of Toubab Krewe

+ Mande comes to Krannert