We have observed the killing of African Americans in varied public spaces in recent years: their father’s condominium courtyard, a gas station, a pavillion in a park, the middle of the street, on street corners, and in their own homes; as well as the recent onslaught of police calls on African Americans in Starbucks, hosting summer parties, at cookouts, selling water, ordering in restaurants, etc.

Consequently, my spirit has begun to ponder: Where exactly do people of color belong? What public spaces can people of color occupy without menace?

For me, nature has emerged as an urgent way of escape. To combat racialized anxiety, I increasingly sought refuge in nature this year.

I began volunteering with a local farm working washpack and harvesting.

Then I planted my own garden.

I began walking more outdoors with GirlTrek and decided to launch a local GirlTrek group — Team Chambana Strides — and traveled to the Rocky Mountains with the GirlTrek Stress Protest.

I celebrated my wedding anniversary in the Indiana Dunes hiking beaches with my husband.

I began studying to become a Master Naturalist through the University of Illinois Extension office.

However, the more I craved outdoor experiences and have enjoyed our weekly local GirlTrek walks, the more I wrestled my complicated relationship with the natural world as the daughter of Mississippians on who fled Jim Crow South for Chicago.

In the introduction to her work Rooted In The Earth: Reclaiming The African American Environmental Heritage, scholar Dianne D. Glave articulates some of the common sources of African American ambivalence about nature:

Scorn, distaste, and fear of nature became the emotional legacy of a people who had been kidnapped from their homelands and forced to make the long journey across the Atlantic Ocean to pick cotton and prime tobacco for often violent and abusive masters; they were finally subject to losing legally owned land to the whites who continued to victimize them long after slavery was banned.

I have wrestled with being the only participant of color in the Master Naturalists program. Furthermore, in this climate of heavy African American surveillance nationally, the legacy of sundown laws across Central Illinois communities and continued residential segregation across Champaign County, it is deeply unnerving to drive into very rural forest preserve sites with no other African Americans present as fellow participants, guides, or presenters. Yet another challenge is the sobering recognition that all of these preserves were formally Native American lands who are no longer in possession of these lands due to forced dispersal. I raise these issues not to blame, but to sensitize the reader to what I am considering as an African American woman each time I arrive to a field trip site.

Other African American outdoor enthusiasts shared some of my concerns in recent articles Candice Pires “Bad Things Happen In The Woods: The Anxiety of Hiking While Black” and Shereen Meraji’s “Outdoor Afro: Busting Stereotypes That Black People Don’t Hike or Camp.”

During the flowering of my outdoor interest, theatermaker Latrelle Bright and I would cross paths periodically during my outdoor excursions and we would inevitably discuss questions of race and public space. So when she presented to me the idea of participating in Journey to Water — a collaborative project between her, Theatre Maker, and Prairie Rivers Networks — I eagerly signed up to participate with a group of African Americans.

Journey to Water is an effort to connect and discuss the relationship of African Americans to water and local water sources. An intergenerational group of 20 African Americans caravaned to Homer Lake for a day excursion and activities this past weekend. The effort was made possible by the Catalyst Initiative grant from the Center for Performance and Civic Practice and partnerships with CU Change Makers and the Champaign County Forest Preserve.

Photo by Latrelle Bright

Photo by Latrelle Bright

Upon arrival, we stopped in at the Homer Lake Interpretive Center to meet with staff, get a brief overview of the grounds, gather maps, use the restrooms, and set our course for the day. The group that Bright hosted was primarily comprised of African American pre-teens and their mothers who are participating in the CEESTEM program created by Dr. Phoebe Lenear, a non-profit organization whose goal is to increase underrepresented minority youth participation in the STEM fields.

Interestingly, as our youth descended from the buses and headed for the play structures near our picnic area, white park visitors moved rapidly to depart the play structures when they say our youth group approaching. Similarly, 100 or so feet from the play structure, a white fisherman gathered his pole and departed the water when we arrived. It was as if our presence set off an internal alarm that triggered immediate white flight.

Photo by Latrelle Bright

Photo by Latrelle Bright

As I looked on observing the arrivals and departures, I hoped the children would not be troubled by it. The children seemed unphased and focused on canoes and kayaks, however their mothers lamented the departures as yet another reminder of the resistance of white people to sharing public space with African Americans.

Nonetheless, despite this initial hiccup, the adults moved to settle in, brought out lunch coolers and art supplies and organized groups for the days activities: painting, hiking, canoeing, and kayaking. I got a nice 1 ½ mile hike in before lunch. After the first round of activities, we lunched as Bright did a public reading of her work exploring African American relationships to water from pre-US settlement to the present.

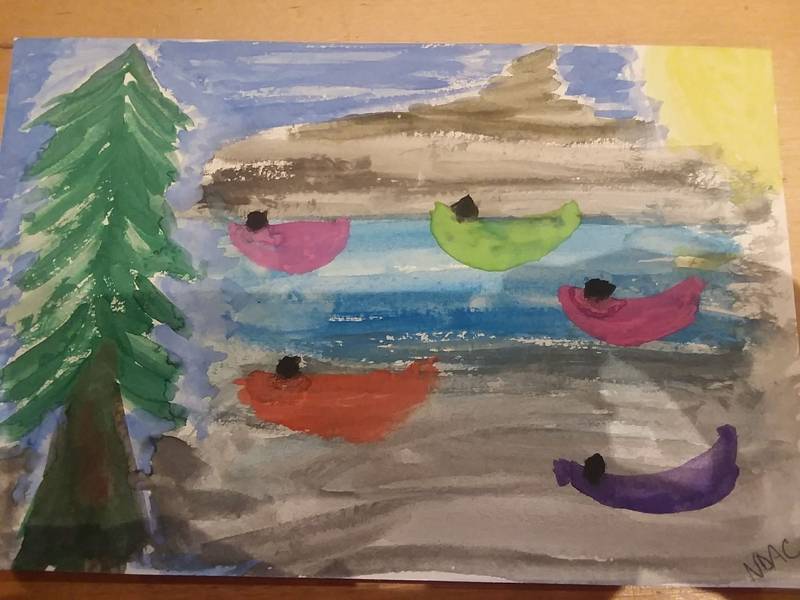

After the performance closed, we then had time to complete another round of activities before departing. This time, I chose to paint. My picture began as just a scene of the lake. However, as our young kayakers and canoers, many of whom were engaging in both activities for the first time, approached us, their courage and ease on the water inspired me to immortalize their journey across the river in my painting.

The outing closed with a sharing circle of participants reflecting on the day and a group photo.

While I reflected on the Journey to Water outing, I heard a podcast from IKAR, one of my favorite faith communities in the US, that captured well my sentiment for the experience.

In “True Seeing,” Rabbi Keilah Lebell reflects on Annie Dillard’s notion of “true seeing” or engaging in a pure, unadulterated encounter where the seer has no expectation of the object she is looking at. True seeing is seeing beyond categorization in order to encounter each being in its uniqueness.

I hope that our local outdoor community can come to “true seeing” regarding who is absent from local outdoor experiences in programs, program content, participants, and in leadership. In this way, such “true seeing” can foster fuller and more diverse experience of the public spaces that we all share and support with public and private dollars.

Photos by Nicole Anderson-Cobb except where noted