rep·a·ra·tion

/ˌrepəˈrāSH(ə)n/noun

the making of amends for a wrong one has done, by paying money to or otherwise helping those who have been wronged.

When beginning the reparations conversation in our community, we must start by accepting that white people have inflicted great pain and suffering upon Black people for centuries. Though Illinois was not a slave state when it joined the Union in 1818, it fully embraced the white supremacy governing the country, and enacted the policies of Jim Crow in the post-Civil War period. We believe reparations are necessary to move toward racial parity in our community.

We see what’s happening in Evanston, a community working towards reconciliation, pledging $10 million towards reparations. The plan is neither fully fleshed out nor perfect, but it will go to a vote on March 22nd. If Evanston can have this discussion, Champaign-Urbana can, too. Of course, we are two different communities in many ways, but it is clear the citizens of C-U welcome change.

We believe the onus is on white people to work to fix these historical inequities, though not unilaterally. We must listen to all parts of C-U’s Black communities. It is essential to accept that every Black person’s experience is unique, and there’s no one single need or one single Black community. Repairing centuries of harm takes time and resources. We must be mindful of falling into the trap of white saviorism, and continuously work to center the needs and wants of historically marginalized communities.

This doesn’t just happen through simply cutting out the endless legal conservatism established over time, but instead by literally granting the Black community the same types of resources and opportunities white generations have used to improve white communities. We must lobby for policy changes and real action, but it is also critical to note that in this country, power (and access to it) is often determined by real, liquid money, and cash in the hand.

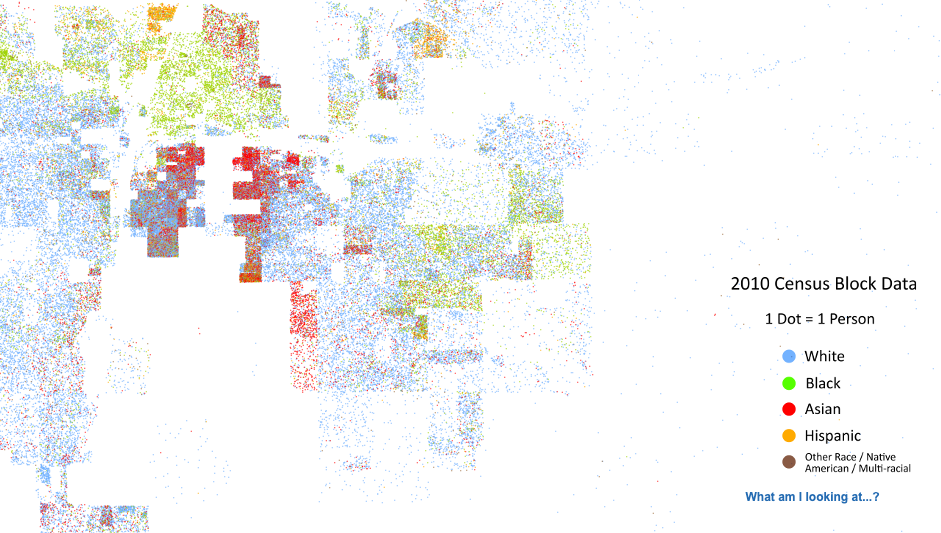

Map of Champaign-Urbana area taken from 2010 Census Data Map, showcasing locations of people based on information collected about race. Image from RacialDotMap.

OUR WHITE COMMUNITY INTENTIONALLY CREATED THIS

White settlers in Illinois stole land from Indigenous people before implementing racist policies against Black people. These settlers stole Indigenous and Black communities’ abilities to grow and prosper in this state. We, lifelong and current residents of Illinois and C-U, have benefitted from these policies for generations, and must put to rest the common “none of us currently living are responsible” narrative.

Look no further than this article in the Public i which goes into great detail about how redlining intentionally created a segregated community in the mid-20th century in Champaign-Urbana. The University of Illinois echoed this policy; even though Black students could enroll, they could not live on campus, and had to find housing in C-U. Though Champaign and Urbana were not Sundown Towns, nearly all of those surrounding this area were.

UNLOCKING HUMAN POTENTIAL

An endless number of scholars believe the path toward true reconciliation is through funded reparations set forth by the government to literally repay Black people for their labor and losses. We know there’s a lot to fix as we look toward our post-pandemic world. This pandemic has exacerbated the institutionalized disadvantages faced by the most vulnerable members of our community, especially our Black residents.

To move forward, we must seek input from our Black communities about their needs. We are learning through Evanston’s reparations discussion that their plan doesn’t go far enough, with members of the Evanston Black community stating the plan would be “detrimental.” It isn’t enough to distribute money from “found” revenue sources like taxes on marijuana. It has to go further than that. A comprehensive plan must focus on the reallocation of funds currently budgeted for projects that will impact predominantly white neighborhoods in favor of projects for predominantly Black neighborhoods.

As Erika Alexander states in this episode of the NPR podcast Code Switch, Black communities have been limited by what they could — and could not — do since the abolishment of chattel slavery and which opportunities — educational, financial, geographic, health — have been available or denied. There’s a “loss of human potential,” she says. To us, this profound future-vision should be adopted by community leaders to bring the reparations conversation to the forefront for actionable change that recognizes this untapped potential. Imagine the growth we could experience as a unified community if all people were treated with respect and dignity, and granted the same opportunities for health, education, and economic gain. Reparations are part of unlocking a better future not just for our Black neighbors, but for all of us here in Champaign County.

Photo by Anna Longworth.

SMALL STEPS ADD UP

Look: We don’t have a plan. But we do have voices and listening skills. Black people exist in the future, and we need to let our elected officials know that. We must tell them to prioritize our future by committing to changes in infrastructure, direct payments through city funding, and to listening to and centering the experiences of our Black friends, family, and neighbors.

We need actionable items with agreeable milestones. There’s money in our community to do so. We realize we can’t make these changes happen overnight, but we must take steps to ensure we not only find ways to generate income from “new” money (i.e. marijuana tax, which will generate an estimated $340K in Champaign and $225K in Urbana next fiscal year), but also carve out what is already available and reallocate those funds and efforts. Look no further than the ongoing Garden Hills conversation, as change is happening slowly but surely.

A few hundred thousand dollars annually could move the dial for future generations, and we must start somewhere to work towards a better future. There is much work to be done, and yes, a lot of money will need to be spent. But when we view and treat people equally, and invest in their futures, our community will be repaid tenfold.

The Editorial Board is Jessica Hammie, Julie McClure, and Patrick Singer.