A few years ago, I was having a conversation about race with someone in my hometown of Vandalia, IL, which is a rural spot of 7,000 people. He said something I can’t forget, something I didn’t expect him to say.

He said, “I just don’t like all of those urban attitudes.”

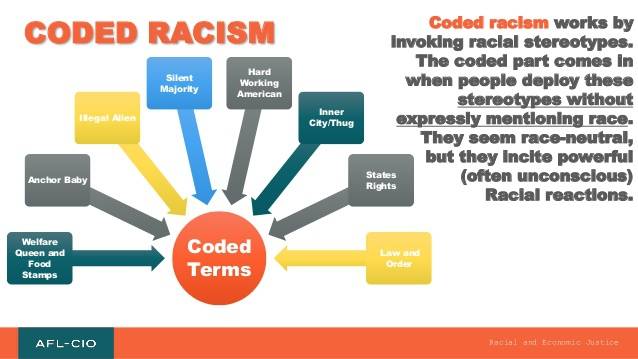

The average person knows that racism is bad; we don’t want to be thought of as racist, and when we have attitudes that might appear to be just so, we can get pretty creative with how we justify those sentiments. We do things like use coded language. Instead of saying, “Black,” we say, “urban,” and those of us quietly holding similar prejudices nod emphatically at the subtle distinction because “it’s not that I hate Black people; I just don’t like this specific kind of Black people.” The average Black man who dresses in Black fashion and maybe sags his pants doesn’t commit crimes, but some will say, “He dresses like a thug,” because if we use the word thug, we can claim to be referring to a specific kind of Black person, and that’s not racist, right? That’s nuanced.

Above: Coded terms are prolific in everyday conversation. Image from the AFL-CIO.

We find so many ways to quietly express our prejudices. We express them by choosing whom we make eye contact with or say hello to. We express them when we choose not to drive certain streets en route to whatever destination. We express them by giving to one homeless person and not another and by having more patience with disobedient children of one race versus another.

Homeowners organizations express their prejudice through their neighborhood agreements, which can include provisions like disallowing the rental of a home to parties that aren’t a “single family.” That is, if you and your friend(s) find a great rental in a great neighborhood that you can afford, you can be barred from renting it because you’re not a family. It might seem innocuous, but such a provision is about wanting only certain kinds of people to live in a neighborhood (namely, people with the income to comfortably afford $2,000/month rent with 1 or 2 household earners, not people with the kind of jobs who would split that rent across 3 or 4 earners).

Chapter 17 of the City of Champaign Municipal Code, titled “Human Rights,” says this:

It is the intent of the City, in adopting this chapter, to secure an end, in the City, to discrimination, including, but not limited to, discrimination by reason of age, color, creed, family responsibilities, marital status, matriculation, national origin, personal appearance, physical and mental disability, political affiliation, race, religion, sex, sexual preference, prior arrest or conviction record or source of income or any other discrimination based upon categorizing or classifying a person which is not based upon factual data about the persons or group and is not related to the purpose for which it is used.

However, in 1994, the City of Champaign quietly expressed prejudice via the addition of section 4.5 to chapter 17 of the Champaign Municipal Code, which reads, in part,

Nothing in this chapter shall prohibit discrimination in the leasing of residential property based upon a person’s record of convictions for a forcible felony or a felony drug conviction or the conviction of the sale, manufacture or distribution of illegal drugs or convictions which are based upon factors which would constitute one of the categories of convictions listed above under Illinois law; provided, that the conviction shall not be allowed to be the basis of discrimination if the person convicted has resided outside of prison at least the last five (5) consecutive years without being convicted of an offense involving the use of force or violence or the illegal use, possession, distribution, sale or manufacture of drugs.

For some reason, in 1994, we decided that instead of disallowing discrimination based on any prior conviction, instead, we should disallow discrimination based on any prior conviction if the convicted person is five years clear of the offense (and any incarceration that might have resulted thereof). Again, it might seem innocuous; after all, we don’t want violent or drug felons living in our nice neighborhoods, right?

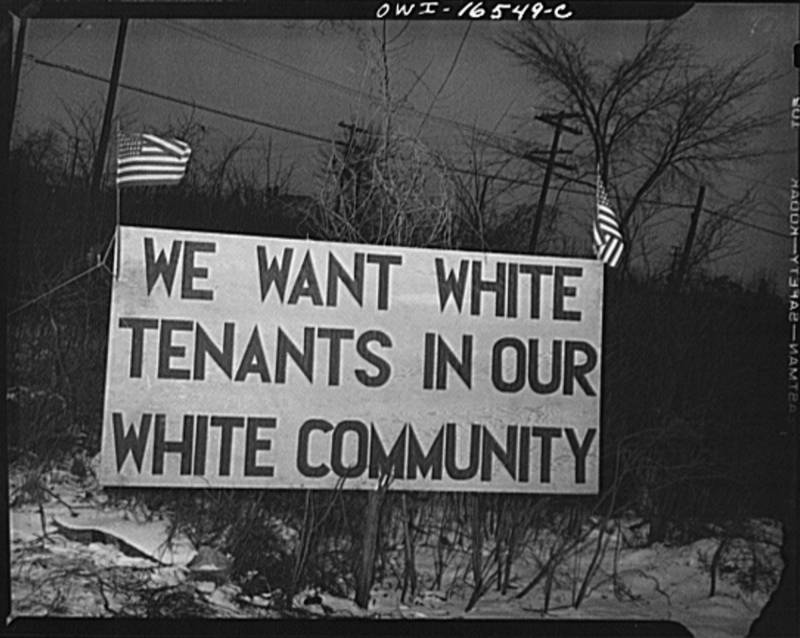

Above: Full-caps racism on display in response to the Sojourner Truth Housing Project. Image from the Library of Congress.

Did you catch yourself nodding along? If you get caught with a baggie of weed in Illinois (10 grams), that’s a misdemeanor. Get caught a second time, that’s a felony. Some very nice people in very nice homes in very nice neighborhoods have 10 grams of weed at home right now. They just haven’t been caught.

Who’s likely to get caught? Well, based on national and local statistics for policing, Black people. What we know from national studies is that while minorities don’t commit crimes at a rate greater than that of Whites, Blacks and Latinos are much more likely to be detained and searched (and with flimsier justification) than Whites. What section 4.5 amounts to, in effect, is housing discrimination not targeted at “crime” so much as it is at minorities.

The Champaign County Board, the City of Champaign Human Rights Commission, and the Champaign County Racial Justice Task Force have all called for the repeal of section 4.5. Champaign City Council member Alicia Beck (District 2) has proposed a study session to begin the process of repealing the offending text in section 4.5, and council members Will Kyles (at large) and Matthew Gladney (at large) have signed on. Two more signatures are needed to effect the study session. Those two signatures can come from these council members:

- Clarissa Nickerson Fourman (District 1)

- Angie Brix (District 3)

- Greg Stock (District 4)

- Vanna Pianfetti (District 5)

- Tom Bruno (at large)

If you care to see people treated equally in the City of Champaign, email your council member (if it’s not Beck, Kyles, or Gladney) or Mayor Deb Feinen and encourage them to sign on to the study session to abolish the quiet prejudice in the municipal code.