January 15th marked the 81st birthday of the late Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. This event, along with another seemingly unrelated event — the broadcast of a number of Westerns on the American Movie Channel — gave me an opportunity to reflect on what theologian Walter Wink calls The Myth of Redemptive Violence.

January 15th marked the 81st birthday of the late Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. This event, along with another seemingly unrelated event — the broadcast of a number of Westerns on the American Movie Channel — gave me an opportunity to reflect on what theologian Walter Wink calls The Myth of Redemptive Violence.

I’m not a big fan of Westerns, mainly because they tend to glorify violence. But there is one Western that ranks among my all-time favorite movies: Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven. (The AMC has broadcast this movie several times during January and it will air once more this Saturday, January 30th at 11:00 a.m.). I like this flick because it doesn’t portray violence and killing the way most other Westerns do by reducing the characters to unfeeling, shallow stereotypes that kill without remorse. Instead, it reveals human beings trying to come to grips with the awful things they have done, as illustrated in the following dialog from the movie:

Schofield Kid: You know how I said I shot five men? It weren’t true, uh, that Mexican that come at me with a knife? I just busted his leg with a shovel. I didn’t kill him or nothin’ neither.

William Munny: Well, you sure killed the hell out of that fella today.

Schofield Kid: <laughs> Hell, yeah. <drinks whiskey> I killed the hell out of him, didn’t I? <begins to cry> Three shots and he was takin’ a shit. <looks down>

William Munny: Take a drink, kid.

Schofield Kid: <drinks whiskey, crying> Jesus Christ, It don’t seem real. How he ain’t gonna never breathe again, ever. How he’s dead. <sighs> And the other one too. All on account of pullin’ a trigger.

William Munny: It’s a hell of a thing killin’ a man. Take away all he’s got and all he’s ever gonna have.

Schofield Kid: Yeah, well I guess he had it comin’. <drinks whiskey>

William Munny: We all have it comin’, kid.

The cowboy who was shot “had it comin'” because he had “cut up a whore.” He had visited the local brothel in order to avail himself of its “services,” as it were, but when the prostitute saw how small his penis was, she laughed. So he took a knife and carved up her face, thus beginning a saga of escalating violence. After this incident, the women of the brothel pooled their money together so they could pay a bounty to any cowboy who shot and killed the guy who cut up the girl’s face.

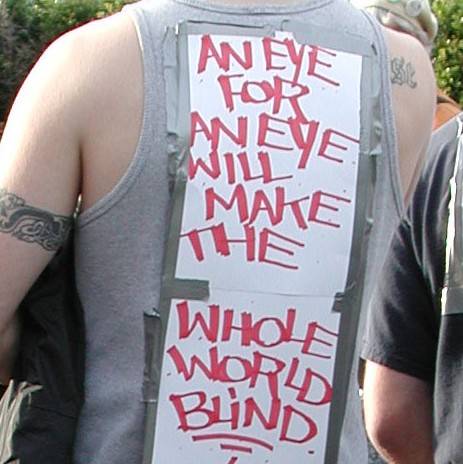

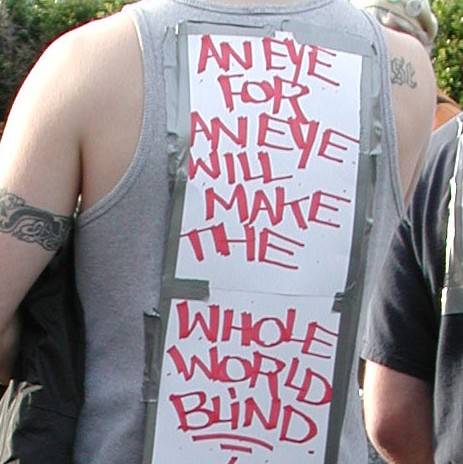

Although we may not think of Westerns as having any kind of theological message, they often play with a theme that can be summed up in the biblical maxim of “an eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth.”

But this phrase is often misunderstood by modern readers to mean something like, “If you knock out my teeth, then your teeth also have to be knocked out.”

But the “eye for eye” law was not created to ensure that people were properly punished. The “eye for eye” law was created to prevent people from being excessively punished.

The idea of “eye for eye, tooth for tooth” can be found in the Hebrew Bible in three places: Leviticus 24:19-21, Exodus 21:22-25, and Deuteronomy 19:21. And again, it was a law that evolved out of reaction to excessive punishment for crimes. In the movie, Unforgiven, we see a couple of examples of excessive punishment. First, the cowboy punishes the prostitute for laughing by cutting her face with a knife. Second, the prostitutes punish the cowboy by having him killed for cutting up the girl’s face.

In the Bible, an example of excessive punishment can be found in Genesis 34, a story commonly called “The Rape of Dinah.”

Dinah, the daughter of Jacob (the leader of one tribe), was abducted and raped by a man named Shechem (the son of Hamor, the leader of another tribe) who then decided he wanted to marry Dinah. So, Shechem proposed to Jacob that everyone from both tribes simply intermarry and they could all be one big happy family. But Dinah’s brothers, led by Simeon and Levi, tricked Shechem and his men by saying, basically, yeah, this is a good idea, but first you all have to get circumcised so you can be Jewish like us. Shechem and his men agreed. Then when they were all sitting around in agonizing pain from cutting off their foreskins and unable to defend themselves, Jacob’s sons slaughtered them, thus avenging Dinah’s rape.

The idea of “an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth” was born in a culture that was struggling to curb this type of excessive violence. “Eye for eye” means that if someone gouges out your eye, you don’t have the right to kill that person or their family or their nation. You can require only at most that their eye also be gouged out.

But whether retaliation for a violent act is equally as violent or excessively violent, it still falls under what Wink calls The Myth of Redemptive Violence.

Wink writes:

The belief that violence “saves” is so successful because it doesn’t seem to be mythic in the least. Violence simply appears to be the nature of things. It’s what works. It seems inevitable, the last and, often, the first resort in conflicts. If a god is what you turn to when all else fails, violence certainly functions as a god. What people overlook, then, is the religious character of violence… This Myth of Redemptive Violence is the real myth of the modern world. It, and not Judaism or Christianity or Islam, is the dominant religion in our society today. (Facing the Myth of Redemptive Violence by Walter Wink)

When Jesus came along, he suggested a very different, even radical, approach to curb violence. In his Sermon on the Mount, Jesus said:

You have heard that it was said, “An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.” But I say to you, do not resist an evildoer. But if anyone strikes you on the right cheek, turn the other also; and if anyone wants to sue you and take your coat, give your cloak as well; and if anyone forces you to go one mile, go also the second mile. Give to everyone who begs from you, and do not refuse anyone who wants to borrow from you. (Matthew 5.38-42)

Jesus is not implying that we should simply give in to violent people and let them trample all over us. Neither should we run away from violent people. Jesus is saying that there is a way to stand up to violence that is neither aggressive nor cowardly.

Wink writes:

When Jesus says, “Do not resist one who is evil,” there is something stronger than simply resist. It’s do not resist violently. Jesus is indicating do not resist evil on its own terms. Don’t let your opponent dictate the terms of your opposition… Don’t resist one who is evil probably means something like, don’t turn into the very thing you hate. Don’t become what you oppose. The earliest translation of this is probably in a version of Romans 12 where Paul says, “Do not return evil for evil.” (The Third Way by Walter Wink)

Walter Cannon, the American physiologist who coined the term “fight or flight” suggests that there are two ways that animals (including humans) deal with stress. We either fight it or we run away. The problem is that fighting makes us just as violent as our aggressors and running away makes us cowards.

Walter Wink proposes that Jesus offered a “third way” to deal with violence. We don’t fight. We don’t run away. Instead, we stand up and resist peacefully thereby exposing the violence, hatred and inhumanity of the oppressors. Some folks don’t believe this works, but as Wink noted:

In just the last few years, non-violence has emerged in a way that no one ever dreamed it could emerge in this world. In 1989 alone, there were thirteen nations that underwent non-violent revolutions. All of them successful except one, China. That year 1.7 billion people were engaged in national non-violent revolutions. That is a third of humanity. If you throw in all of the other non-violent revolutions in all the other nations in [the twentieth] century, you get the astonishing figure of 3.34 billion people involved in non-violent revolutions. That is two-thirds of the human race. No one can ever again say that non-violence doesn’t work. It has been working like crazy. (Ibid)

I am thankful for the lives of Mohandas Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. who showed us that non-violence does, indeed, work.