This essay was originally published by Will Leitch in Deadspin on March 1, 2010. It has been republished here in its original version. Our thanks to Mr. Leitch and Tommy Craggs of Deadspin for granting us permission to republish the essay.

And much thanks to Jason Zylka for suggesting the article.

The first time I was ever published in a book was 1997. It was because I’d found Roger Ebert’s email and asked him a question.

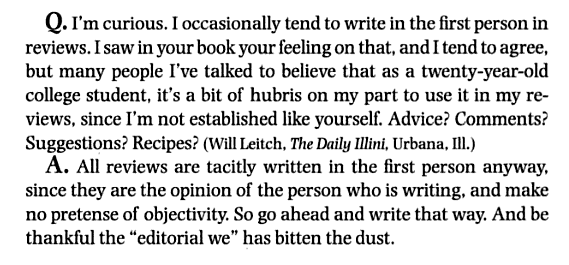

You can find the link right here, from Ebert’s book Questions for the Movie Answer Man. Here’s the question:

This was not the first question I had asked Ebert. (Considering the royal “we” construction I would use during my days as editor of Deadspin, it has a certain historical irony.) Ebert was an alum of the University of Illinois, and he was the reason I was there. He grew up in Urbana, just 45 miles up the road from Mattoon, my hometown, and as a high school sophomore slowly realizing he enjoyed plunking away on his typewriter far more than any job his sleepy town would have to offer, I found Ebert to be an inspiration. Thanks to the Esquire story about him that has moved millions, and of course his prolific and hypnotic Twitter feed, Ebert is now a national icon. (This will be cemented with his appearance on Oprah tomorrow, the closest our culture comes to knighting anyone anymore.) But to me, Ebert was glimpse of a better life: He was proof there was a ticket out. I went to study journalism at the University of Illinois, simply, because I wanted to be Roger Ebert. He was a Central Illinois kid, from the middle of nowhere, who was known worldwide simply because of his writing and work ethic.

And oh, that writing! Ebert writes about movies in a way that celebrates movies and surpasses them. Calling him a “film critic” almost diminishes him: All Roger Ebert reviews are really about life itself, about the little mysteries about ourselves and our world that the illusion of movies attempts to resolve. Ebert never wastes a word: He writes in an economical, unfailingly intelligent way, the shorthand of an old newspaper man. His reviews almost always transcend the movies they’re about, even the good ones. He’s funny, sharp, critical but never mean, and always with a big, sweeping, humanist bent.

Here’s a great example. Right in the middle of his review of Shopgirl, a movie Ebert likes more than just about anyone on earth, he drops in this, almost out of nowhere:

I’ve been around a long time, and young men, if there is one thing I know, it is that the only way to kiss a girl for the first time is to look like you want to and intend to, and move in fast enough to seem eager but slow enough to give her a chance to say “So anyway …” and look up as if she’s trying to remember your name.

Ebert’s writing is gentle, calm and infectious. He trusts his readers not to be morons. He writes for who he imagines to be the ideal reader, which is actually the reader we all wish ourselves to be. Those who thought of him as the fat man with the thumb always missed the point. He became who he was because of his work. He did it the right way.

I wanted to be him, desperately. My first day in Champaign, I showed up at the Daily Illini, where Ebert had been the editor-in-chief, and begged the entertainment editor to let me write movie reviews. He was the reason I did anything.

Ebert, unlike fellow U of I journ alums Hugh Hefner and Robert Novak, was a regular presence on campus. He was a firm supporter of the school and the paper, and had invited the DI‘s editors to email him anytime they had any questions or needed any support. The first time I ever got drunk, off four wine coolers that sent the world spinning, I finally built up the nerve to take advantage. The desk in the EIC office had been passed down through several generations, and it was DI lore that Ebert had once had sex on it. Blitzed on Bartles & Jaymes, I sent a note to REBERT@COMPUSERVE.COM.

Sir, Mr. Ebert, this is Will Leitch, an editor at the Daily Illini. I’ve had a bit to drikn and am going to just ask. There is an old story that you had sex on the EIC desk. Is that true? Everybody wants to knwo.

Sorry for this.

Best,

Will

The next morning, shaking off my first of many hangovers, I checked my email and found that Ebert had responded. He was more graceful and polite than one could consider reasonable.

Your interrogation has made me laugh this morning. I would love to say that I enjoyed fornicating on the Daily Illini desk, but if I remember it correctly, I suspect the splinters would have made the endeavor unpleasant. It is reassuring that professors down there are still teaching their students to ask the tough questions.

RE

Because I was 19, I took this as an invitation to keep bothering Ebert, and over the next two years, I emailed him regularly, with questions about my career, with movie reviews I’d written and hoped he would offer tips on, with requests for advice on writing, on life, on the tough job market that awaited me upon graduation. Ebert wrote back to every single one, with lengthy and heartfelt missives that were far more than a snot-nosed kid clearly getting off on Knowing Roger Ebert deserved. I have no idea why he did it. He told me “that this is important to you as it is, that’s a very large percentage of what you need, really.” He emphasized that such ephemera like “career” and “success” were mostly beside the point. “Just write, get better, keep writing, keep getting better. It’s the only thing you can control.”

Ebert even recommended me for a job stringing movie reviews for the suburban Daily Southtown newspaper. For the first one — the Robert Downey Jr. movie Restoration — I borrowed my friend Mike’s car and drove up to a Chicago screening room. I didn’t know Chicago well and of course got lost, just sneaking into the theater right as the lights were going down. After the movie, I walked out to the elevator, and standing there, was Ebert.

“Sir,” I said, talking very fast. “I’m Will Leitch, from the DI. I wanted to thank you and say what an honor it is to me. I can’t thank you enough for what you’ve done. I promise not to abuse it.”

Ebert was bigger then, and his hand was meaty and sweaty.

“Of course, Will, I’m happy to help you in any way. You have talent, and anyone from the DI is a friend of mine,” he said. “Actually, I’m going to be in Champaign in a few weeks for a screening at the New Art, and I’d love to meet with you and some of the staff beforehand. Is Papa Del’s still open?”

Two weeks later, Ebert was entertaining me, my friend Mike and a few select editors — the fight to be included at the dinner was fierce and still angers some today — at Papa Del’s. (We had four pizzas, and Ebert ate 1 1/2 of them.) He took our questions, we talked about journalism and movies (he and I had a fierce debate as to whether or not Harry Connick Jr. was in the Holly Hunter movie Copycat: I was right, though nobody had an iPhone to prove it at the time), and he told us stories about the old days without ever romanticizing his good old days at the expense of ours. He was not Roger Ebert, the guy on television. He was just the fun guy eating pizza, dishing about Gene Siskel — he absolutely could not understand how that man could care so much about the Chicago Bulls, a stupid sports team — and having a grand time. We sat there for three hours. None of us wanted to leave, including him.

At the end of the night, Ebert took me aside. “I understand it’s your birthday tomorrow, Will,” he said. (It was. I was turning 20.) “Well, I have a gift for you. It’s a scoop. You can run it in the paper tomorrow. I received a print of a movie that’s not out yet to show at the theater tomorrow. You can have the exclusive: It’s Mighty Aphrodite, the new Woody Allen film.”

Once I finished humping Ebert’s leg, I went to the office and wrote the story, and the next evening, we watched the movie at a crowded New Art. (This was before Ebert’s yearly Ebertfest in Champaign.) As the credits from the new Woody Allen movie rolled, Roger Ebert, the man I’d tried to pattern my entire life after, walked over to me and said, “So, Will, what did you think?” So that was a pretty good birthday.

I graduated the next year, corresponding with him less often (though enough to show up in that book excerpt), and then moved to Los Angeles, where I hoped to start my own career as a film critic. I had a mailing list with all my reviews, which Ebert was on, and he’d occasionally respond to one and ask me how things were going. That happened less and less, and eventually it stopped. By the time my brief film critic “career” in LA had ended, and I’d retreated to the Midwest and The Sporting News, I’d almost completely lost touch with him. In February 1999, Gene Siskel died, and Ebert hired Richard Roeper to replace him, someone I found to be a lightweight haircut in a tie, a “lifestyle columnist” pretending to be a movie critic, someone who was beneath Ebert … someone meant only to prop up Ebert and make him look smarter. Roeper was not a worthy sparring partner. I found myself no longer watching At the Movies, a show I had once never missed.

Meanwhile, the Web was beginning to emerge, and we young turks, swept in during the dot-com boom, all thought we were punk rock gods, ready to kill our idols. Ebert began to feel like the old guard: In the wake of Siskel’s death, he had become a ubiquitous presence on television, at the expense of his writing, I felt. In 2000, when I’d moved to New York and, like everybody else, was being paid far too much just to be told I was part of the next “MTV Generation” of Internet stars, I thought I knew everything. You had to burn down the past. These were the days of We Live in Public, of Pets.com, of bringing your dog in the office, of Webvan, of espnet.sportszone.com. We all thought we were hot shit.

And I was ready to make my own name. My editor at Ironminds, the old Web magazine I moved out to New York for, had heard me drunkenly bitching about Ebert at a bar the night before and suggested I write about him. “Put him in his place,” he said. “Yeah: It’s our time now,” I said. We were all so, so stupid.

So I did. The next morning, Ironminds ran a piece called “I Am Sick Of Roger Ebert’s Fat F——ing Face.” The piece — which, mercifully, is no longer online — wasn’t as virulent as that headline would imply, but I did use that exact line in the piece, and I did make a few cheap shots about his weight. The thesis of the piece was that Ebert’s work was suffering because he was on television all the time, but that’s not really what it was about: It was me lashing out at Daddy, trying to make my own name, trying to feed off his. That’s not what I thought I was doing at the time. But that’s absolutely what it was.

Jim Romenesko’s MediaNews, which is popular now but was downright Drudge-esque at the time, picked up the piece. The email came almost immediately. I stared at my inbox for five minutes before I worked up the nerve to open it.

Will —

I have always tried to help you, and you know that. I am not sure what you were trying to do with your piece — if you object to me being on television, there is a dial to the right that will take care of that problem for you — what issues you might be dealing with, but I am certain you will grow to regret writing it someday. If you were trying to make a point, I fear you are not in control of your instrument. I wonder if you feel shitty this morning, now that that piece is out there. I know that I do.

RE

I wrote him back, completely backing down, apologizing, but the damage obviously had been done. I did feel shitty, instantly, and have ever since. A year later, I was working for Brill’s Content’s All-Star Newspaper — immortalized here — where I ran an early incarnation of a blog, linking to the best newspaper writers in the country every morning. As the job required me to do with all the writers we selected, I sheepishly emailed Ebert to tell him he was on the roster. He wrote back:

Does this mean you’re no longer sick of my fat fucking face? 🙂

It’s an honor. I hope you’re well.

RE

That was the last time I’ve ever interacted with him. When he went in for his first surgery, the first of the many that would ultimately leave him with the afflictions documented in the Esquire piece, I sent flowers and a card to the hospital. I have no idea why. It was stupid, really. I couldn’t take back what happened, and I doubt he really ever remembered or cared anyway. I never tried after that.

I kept tabs on all his surgeries, and worried about him, and during his break from writing, missed receiving his Movie Yearbook (my sister’s yearly Christmas present) and having his voice — his voice — guide us through movies, through everything else. When he was able to write again, he came back with a vengeance, illuminating us not just on film, but on the world we live in, on politics, on religion, on love and wine and old Central Illinois fast-food restaurants. He just wrote: He did what he’d been doing the whole time, what he was sent to earth to do. I forgot my personal history with him and just enjoyed his work. He became a larger influence on me than he was when I was growing up. He is a man who has done it the right way.

So, as you watch Ebert on Oprah this week and see him, ready for his closeup, the center of the world at last, if you wonder to yourself, “They’re making him into some sort of saint. Is he really that nice of a guy?” … just know that, yes, he really is that nice of a guy. But more than that, he’s a wonderful, soulful writer who is better, and more devoted, than just about anyone in the game. He’s been my personal hero for 25 years, but he belongs to the world now. I’m just honored to have gotten to know him as briefly as I did, whether or not I deserved it, whether or not I was mature enough to handle it. Ebert’s a national treasure. I couldn’t be more ecstatic that so many people finally realize it. He did it the right way all along: He did it by writing, and being, resolutely, himself.