Murphy’s Law of the Midterm

Or,

It’s Pointless to Complain About Unintended Consequences When We’re Incapable of Ever Thinking Past the Next Election Cycle or Quarterly Earnings Report

University of Illinois football player Chris Jones is facing felony battery charges for allegedly hitting two men in the head on Sunday, July 3. Within hours of the incident, the chatter on blogs and message boards (our publicity first responders) began to include allegations of “hate crime.” Apparently, the two men that Jones allegedly attacked may be, or may have been perceived to be, gay. According to Assistant State’s Attorney Scott Larson, the two men were walking down Daniel Street, holding hands, when Jones drove by in his car and called them derogatory names. Larson said that Jones then got out of the car, called the pedestrians more nasty names, and proceeded to strike them both in the head with his fist.

From The News Gazette:

Larson said Jones, a defensive tackle for the Illinois team, told police that he had been “jumped” by one of the men a week earlier.

Larson noted for Judge Rich Klaus that Jones weighs 320 pounds while the alleged victims weigh 140 and 165 pounds. Larson said the attack was recorded on a security video.

——-

In what follows, I would seek to raise some questions regarding the validity and value of hate crime legislation, and express my skepticism regarding its intellectual basis in the law, along with my concerns as to what it portends for the future of criminal justice in America.

If I have not painted a sympathetic portrait of Chris Jones, that is fine; what I would like to suggest has nothing to do with defending violence, especially violence toward those that are historically (and often presently) vulnerable targets. And I would not sugarcoat what may be the ugly reality of this incident; that would only serve to undermine the integrity of the argument, which has everything to do with the actual facts of the situation. Again, the reported facts: Jones allegedly drove by two men holding hands, called them names, got out of the car, called them more names, and then punched them each in the face.

This is what a prosecution would have to work with.

———-

Hate crimes are typically two-tiered crimes, meaning that the underlying act is a crime itself, and an additional crime has been placed upon the intent or motive for carrying out the underlying crime. Conceptually, it’s a lot like a charge of and prosecution for terrorism, whereby the motive and intent of the perpetrator carries so much weight that a greater crime is inferred into the (relatively) straightforward acts of property damage, battery, or murder that comprise the terrorist act itself. This is an illustrative example, and something that I will return to later.

The problem is that motive and intent are inherently vague and squishy concepts, requiring the prosecutor, judge, and jury to gaze into the mind of the accused and make a determination of guilt based on supposition and extrapolation from certain external events that may not be crimes themselves.

That there may be a security camera recording of the campus attack makes this particular event a convenient one for analyzing the problems of prosecuting hate crimes. A video recording (though fallible) can be a damning or exonerating piece of evidence. There is the act itself, on digital celluloid for all to see. Some event occurred. There. In objective reality. An easy felony assault and battery conviction. Another notch in the prosecutor’s belt, and this won’t even go to trial.

But let’s add a hate crime charge to the mix. Now what? Let’s imagine, for sake of convenience, a different battery definitively occurred, with the same fact pattern as described by Assistant State’s Attorney Larson.

Two men are walking down the street, holding hands. That could be a sign that they are gay, or might provide evidence as to why one would think they were gay. It doesn’t, however, provide incontrovertible evidence that they were beaten because they were gay. *You* have to make that inference.

Again, we are “lucky” that in this hypothetical example, the perpetrator yelled anti-gay epithets out the car window, then went to the trouble to stop the car, get out, and scream more gay slurs before assaulting the victims. Go ahead and imagine the nastiest anti-gay things you can think of. And there’s audio recording, to boot.

Now we’ve got evidence. Evidence as solid as one could hope for to bring prosecution for a hate crime.

And yet, we have to ask, “what do we really have?” What really happened? Anti-gay speech and then battery. It is difficult to envision how there could be any hate crime prosecution, any hate crime at all without the assailant’s verbalization of his interior thoughts. And that is the essence of the hate crime—thought crime.

It’s true that hate crime legislation doesn’t criminalize hate speech itself without an underlying act. Yes, you can drive down the street and call someone a “fag” without fear of prosecution. But it is absurd and disingenuous to claim that speech (and thus thought) is not, in some way, criminalized within the underlying act. And, as vile as that speech might be, I get nervous when the government is in the business of attaching felony charges to words and thoughts they don’t like.

To be clear, I’m not screaming for the government to be shut down or eviscerated of its necessary functions and powers, and I surely disagree with the willfully blind definition of “freedom” as the right do whatever I want so long as I *might* create a job or two.

Nevertheless, given our nation’s long-standing taste for violence, political repression, fraud, and theft, both abroad and at home, I think a healthy skepticism is warranted.

———-

In other words, it’s not so much the application of federal protections to vulnerable groups that I find worrisome, rather it’s the intellectual and analytical precedent that is set in constituting new and distinct crimes based upon motives. Laws have a tendency to start small, and then, via expansive interpretation, grow fat and bloated until they are unrecognizable to their original purpose.

Welcome to the Parade of Horribles.

You don’t have to be paying much attention to sense that the government and establishment seem to be in a state of terminal failure. Eschatology is heavy in the air. And it isn’t because of a meteor crashing to earth, the sun going supernova, or even Jesus returning to judge the quick and the dead. It is because of choices we have made, individually, collectively, at home, and in the halls of government. Our economy, educational system, natural resources, and culture at large are in dire shape and we need a system-wide overhaul post haste.

Problem is, we have so much invested in the status quo that everyone is digging their heels in, claiming the answer lies in the application of a bit of concealer and makeup — raise or lower the marginal tax rate, cut the corporate jet loophole, leave 10,000 troops in Iraq instead of 40,000, etc. Meanwhile, zombies and teenage gladiators roam the ravaged post-apocalyptic landscape of our depressingly-prescient popular culture.

Before you decide that I’ve completely diverged from the topic at hand and gone off the deep end, let me try to bring it all back home…

If we’re to overcome the inertia that is leading us down the path to considerable suffering, it is going to take thought, speech, action, and mass-movement that is seriously anti-government and anti-establishment. This, at a time when it is increasingly difficult to organize, due to both well-planned structural impediments as well as general apathy and disengagement.

Our government has rarely had a moral qualm with quashing serious dissent. Pick your favorite episode. If the establishment feels that its power and resources are in jeopardy at the hands of (even peaceable) “revolutionaries,” do you think it will hesitate to use every trick available to maintain itself? Including imprisonment for thought and speech crimes? Should you, the well-intentioned leftist/liberal/progressive be helping them in that effort?

I will readily admit, this is a somewhat tenuous prophecy, but then I’m happy to play Cassandra.

And just how tenuous is it?

- In June of 2009 Attorney General Eric Holder declared the need to toughen U.S. hate crimes law to stop “violence masquerading as political activism”. If violence can masquerade as political activism, can the converse also be true? At what point, and at whose discretion will political activism be recast as violence and criminalized?

- Daniel McGowan was arrested and charged in federal court on multiple counts of arson and conspiracy on May 21, 2001. The federal prosecutors initially sought a terrorism enhancement, and McGowan was facing a minimum of life in prison for what amounted to (extremely serious and expensive) property damage. McGowan ultimately accepted a plea agreement in 2006. He is now serving time in the Communication Management Unit at USP Marion in Illinois. According to the FBI and DOJ, ecoterrorists (or vandals and arsonists, if you prefer) like McGowan constitute the “number one domestic terrorism threat.” Fitting then that Daniel is doing his time at the CMU (I highly recommend you give these facilities a google) with a bunch of political prisoners, mostly Arabs and Muslims detained in the War on Terror.

- In 2010, a bill was introduced in the Washington State Senate which was self-described as “an act prohibiting terrorist acts against animal and natural resource facilities.” It defined “animal rights or ecological terrorist organization” to mean “two or more persons with the primary or incidental purpose of intimidating, coercing, causing fear with the intent to obstruct, or impeding any person from participating in an activity involving animals or natural resources.” That is shockingly broad language. The bill essentially marked civil disobedience as terrorism, and further criminalized “communications…used to…publicize…ecological terrorism.” So, get together with a friend to discourage the consumption of genetically modified beef, and whoops, you’re a terrorist.

The language was taken almost verbatim from previous bills in Texas and Tennessee. So far, such legislation has not been enacted, but what if the political will were to shift slightly? What precedents are in place for criminalizing speech as violence?

- In September of 2010, the Washington Post reported that the FBI improperly investigated left-leaning U.S. advocacy groups after the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks. FBI agents “put activists on terrorist watch lists even though they were planning nonviolent civil disobedience.”

Maybe you have unquestioning faith in the guy now in charge. But what happens when there’s a change of guard? And have you seen who is lining up to run the country? If you let your friends run roughshod over the law, there’s no complaining when your opponents take power. That goes for you too, conservatives.

——–

Ok. If you haven’t already skipped down to Tracy’s more concise and methodical (how could it not be?) defense of hate crime legislation, and you’re weary of end-times prophecies, let me finish in the here and now, or at least some possible here and now.

Chris Jones is not being charged with a hate crime. This decision was made due to the fact that harsher punishments are available for the simple assault and battery charges. But that is not always the case. Often, hate crime charges serve to stiffen the penalties based on the victim’s real or perceived race, gender, religion, sexual orientation, etc.

And not only do hate crime laws allow for an imbalance in sentencing, but they can also provide millions in federal funding to local law enforcement agencies to help in investigating and prosecuting hate crimes. Does this create the incentive for local law enforcement to prioritize the prosecution of one violent crime over another in order to access those funds?

Do we really care that much about the motivation behind the crime that we are willing to overlook these imbalances, and to risk perversion of the law’s application?

It leaves a bad taste in my mouth to push for harsher sentencing as a matter of policy, and simply for its own sake.

If we are worried about inequitable application of the law to the detriment of vulnerable groups, would we not be better off changing attitudes of police and prosecutors? Hate crimes can allow the feds to bypass local law enforcement, the allure and benefit of which is understandable given the history of local failures based on discrimination, but should the solution be to criminalize motives for violence, rather than addressing the violence itself?

Hate crime laws do not solve our social problems, prevent harrassment, violence, or discrimination. They just mete out stiffer penalties. The war on drugs is a failure for many of the same reasons. Increased sentencing does not keep people from using drugs. Why address the underlying problem when you can simply make a lot of noise about addressing it?

How much time, money, and energy have gay activists spent on giving prosecutors more weapons, increasing the power of the police, and generally fueling the “law and order” society that Richard Nixon so successfully politicized through demonization of hippies, panthers, and queers. Now we’re lining up to continue his program? What a waste. Wouldn’t some of that energy be better spent on furthering anti-discrimination legislation for housing and employment?

But perhaps you’re a tough-on-crime liberal and you want to see violence punished and punished severely. If you don’t like to look at the criminal justice system through a precautionary lens, and you hold no deep-seated suspicion over the expanding police state, then try this:

Imagine a family member is beaten, raped, and murdered, but by someone who had no particular hatred for that family member’s gender, race, or orientation.

Should the murderer be prosecuted to a lesser extent of the law?

~~*~~

Begin Tracy Nectoux’s opinion

On July 3, 2011, college freshman and new Illini football recruit Chris Jones assaulted two gay men on East Daniel Street in Champaign. The two men were holding hands, and Jones first taunted them (allegedly) and then hit each of them in the face (assuredly).

We do not know all of the facts of this assault. We don’t know if Jones’ taunts were anti-gay slurs. We don’t even know if he hurled any taunts at all. We do, however, know that an assault occurred because a security camera recorded it.

Jones’ preliminary hearing is Thursday, July 14, but he won’t be charged with a hate crime. Julia Rietz has said that “[t]here is evidence to suggest that the victims’ sexual orientation was the basis for the battery, but we are better off charging it as aggravated battery.” This is because an aggravated battery conviction brings a harsher sentence — two to five years, as opposed to one to three.

Rietz’s decision angered some people and they expressed themselves in my weekly column The Rainbow Connection. It was those comments that led me to look around online to see what others were saying (and to also keep up with developments on the issue). I happened across a site called IlliniLoyalty.com, and sure enough they’d started a thread about Jones’ arrest. I decided to follow the thread because the community there was providing quick, updated information. I soon found that while most were posting on the specific incident, there had developed a tangential conversation about hate crimes laws. A few on the forum are proponents of them, but more seem to be against them, or at least they question their validity. I should stress that none of the people involved in the conversation are saying anything even remotely negative about gay people. These are — for the most part — intelligent, mature, well-spoken people.

I’m not writing this article to wag my finger at anyone who doesn’t agree with hate crimes legislation. I’m writing to explain why I’m a proponent of these laws and to perhaps provide more understanding and information regarding them. As I read the IlliniLoyalty boards, and as I watched the few proponents of hate crime laws struggle to defend them, I wanted to jump in and help. I also wanted to jump in and refute statements like “hate crime laws are redundant” and “crime is crime.” So, this is my chance to do that.

I read George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four at the impressionable age of sixteen. And coming of age in Reagan’s America, I saw everywhere (or thought I saw) the warning signs that book foretold. So when I learned about hate crime laws (we didn’t call them that then, but that’s what they were), my mind immediately conjured “thoughtcrime.” To me, people receiving harsher sentences because of what was going through their minds at the time they committed crimes seemed too frighteningly Orwellian for comfort. And I confess that my thought process didn’t progress any further than this: “Hate crime laws = thoughtcrime = wrong. The end.”

Later, during the mid-nineties, another reason to distrust this legislation reared its head: political correctness. PC language was all the rage back then, even at my college in Shreveport, LA. I began to see hate crime legislation “for what it really was”: harsher punishment for politically incorrect crimes. Special rights. “This is going too far,” I thought, “Crime is crime, and everyone should be treated equally under the law. No special privileges and no special punishments.” I was still thinking this way when Matthew Shepard was murdered in 1998. And I continued thinking this way when President Bill Clinton began encouraging Congress to extend federal hate crime legislation not only to gay people, but to women and people with disabilities as well.

But a lot has happened in the twelve years since Clinton reintroduced this topic (with a gay spin!) to the country. And a lot has been said on both sides. The so-called “Matthew Shepard Act” took over ten years to become law. And I’ve progressed from being against this legislation to fully supporting it.

Hate crime laws have existed in America since The 1964 Federal Civil Rights Law. This law, along with the 1969 Federal Hate Crimes Law, allows federal prosecution of anyone who “willingly injures, intimidates or interferes with another person, or attempts to do so, by force because of the other person’s race, color, religion or national origin” while that person is engaged in federally-protected activity. (emphasis mine)

In 1990, President George H.W. Bush signed the Hate Crimes Statistics Act. This legislation is the “first federal statute ever to recognize and name gay, lesbian and bisexual people” (National Gay and Lesbian Task Force). And though the bill contains a ridiculously insulting caveat against using federal funds to “promote or encourage homosexuality,” these statistics became enormously important when fighting for more protections for LGBT people.

In 1995, The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act (which includes the Violence Against Women Act) increased the penalties for civil rights-related crimes committed against persons due to “race, color, religion, national origin, ethnicity, gender, disability, or sexual orientation” (sec. 280003, pg. 301). This Act of Congress only applied to federal crimes and federally-protected activity.

Finally, on October 28, 2009, President Barack Obama signed into law the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act. This law expands the 1969 Federal Hate Crimes Law to include crimes “motivated by prejudice based on the actual or perceived race, color, religion, national origin, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, or disability of any person.” The bill also removes the “federally-protected activity” prerequisite and requires the FBI to track statistics on hate crimes based on gender and gender identity. (H.R. 1592; S.1105.IS). Moreover, this Act of Congress is the first federal law to provide legal protections to transgender people (National Center for Transgender Equality).

To explain how I progressed from distrusting hate crime legislation to being a staunch proponent of it, I first need to refute my own past issues.

1. Hate crime laws are the equivalent of thoughtcrime laws.

I was a bit of an alarmist here, I confess. Hate crime laws punish criminals because of their crimes, not their thoughts. However, the motive for the crime is taken into account when proving the conviction, and this is nothing new in criminal law. If people want to, they can fantasize about beating the crap out of Muslims as much as they want. But no one is going to bother them until or unless they actually act on those fantasies.

This isn’t a crime (and you just know what they’re thinking):

2. Hate crime laws are simply politically correct legislation

This one was harder to let go. But I’ve continued to read the literature and listen to the debates taking place over the past decade, and I came to understand that when someone is harmed because of — in Obama’s words — “what they look like, who they love, how they pray, or who they are,” — the crime isn’t just about that one particular victim. The crime isn’t personal to that victim, but rather it’s personal to everyone in the victim’s demographic.

This is why the commenters were so angry and upset in my column last week. If the two men on West Daniel street were, in fact, attacked because they were gay, then Chris Jones was threatening every gay man in this city. Actually, he was threatening gay people, period. This is why commenter Clear as Day wrote, “And same sex couples beware, … go BACK in the closet.” When one member of a demographic is targeted because of his or her minority status, all of the members of that demographic have been targeted as well. That’s why the commenters are furious, and that’s why they want what happened to be treated as a hate crime, because an assault on one is a promised assault on many. When they happen, they’re sending a warning to an entire group of people.

Additionally, victims of hate crimes do not simply need to heal physically. The mental and emotional stress and fear from which they have to recover are markedly greater than those recovering from nonbias crimes. And these aren’t just my “feelings” on the topic — there are studies to back it up. Take anti-gay hate crimes as one example. These create a “ripple effect” in the entire gay, lesbian, and bisexual community. And those who are gay and Jewish or gay and black experience a “double pull,” or stronger negative effect. It takes twice as long to mentally recover from a hate crime, as the victim often suffers from internalized hate and depression while recovering (“The Ripple Effect of the Matthew Shepard Murder,” by Monique Noelle, American Behavioral Scientist).

In a 1999 study of 2,259 lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals, “recent hate crime victims display significantly more symptoms of depression, anger, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress” than lesbian and gay victims of nonbias crimes:

Gay and lesbian hate crime survivors manifested significantly more fear of crime, greater perceived vulnerability, less belief in the benevolence of people, lower sense of mastery, and more attributions of their personal setbacks to sexual prejudice than did nonbias crime victims and nonvictims. (“Psychological Sequelae of Hate Crime Victimization Among Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Adults,” by Gregory M. Herek, et al., Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology)

The “severe emotional and psychological distress” of hate crimes on ethnic minorities are similarly apparent (see “Petition for Inquiry on Hate Speech in Media,” by The National Hispanic Media Coalition; see also “Racism: Perceptions of Distress Among African Americans,” by Vetta L. Sanders Thompson, Community Mental Health Journal).

It’s these issues that led me to conclude that charging a harsher sentence — a sentence that particularly points to not just the crime itself, but the motive behind it, and the long-term effect on the victim — is fair. And, not only that, it’s necessary.

And now, other arguments against hate crime laws that it never occurred to me to worry about:

1. Hate crime laws limit free speech.

This is one that seems to be a no-brainer, but it comes up often, especially among the religious right. The worry seems to be that their ministers will have to stop preaching sermons about the negative effects of the “gay lifestyle” from their pulpits. For the risk — as they see it — is that if a minister preaches an anti-homosexual sermon, and one of his flock leaves church and rapes a lesbian, the minister will be held accountable.

Anyone with even a seventh grade understanding of the Bill of Rights, and especially the First Amendment, knows that this would never happen.

This guy is practicing his first amendment rights:

Whoever painted this sign, however, has committed a hate crime:

The difference? Public and private property. Bill of Rights. First Amendment.

Having a neighborhood meeting to express concern about the “unwanted element” moving into your nice neighborhood is perfectly allowable under our Constitution. Throwing a brick with this message through a four-year-old kid’s bedroom window? That’s a hate crime.

Painting your particularly favorite ethnic group on a public building to express your unique, graffiti artist specialness may be nothing more than a petty crime that might cost you some beer money if you get caught.

But going into a “largely Jewish” neighborhood and painting this on every streetlight is a particularly unnerving hate crime for the residents there to experience:

Hate crime legislation doesn’t have anything to do with free speech. It doesn’t have anything to do with speech at all. And the only thing that it has to do with bigotry is the violence that results from that bigotry.

2. Hate crime laws don’t deter crime.

My reading suggests that hate crimes against African Americans has drastically decreased since the 1960s. I don’t have hard numbers for this, mainly because collecting hate crime statistics only began in 1990. The 1992 FBI Hate Crime Statistics report shows 7,442 hate crimes committed. Its 1996 report shows 8,759 hate crimes, with a breakdown of:

- 63% race

- 14% religion

- 12% sexual orientation

In 2001, there were a whopping 12,020 victims of hate crimes (pg. 10–13 of report):

- 5,290 based on race (46%)

- 2,004 based on religion (18%)

- 1,592 based on sexual orientation (14%)

Here’s what the 2004 percentages looked like:

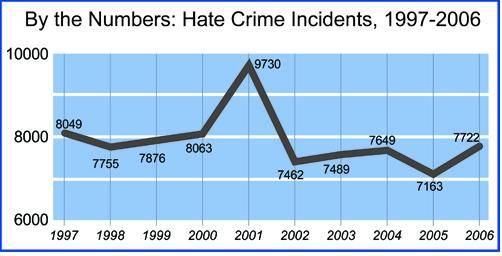

In 2007, the FBI provided us with a handy, but poorly-drawn 10-year-anniversary chart:

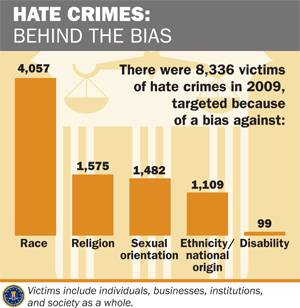

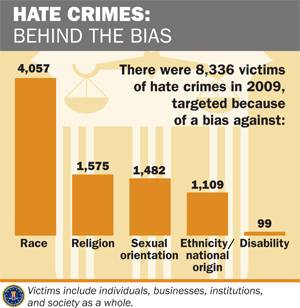

The 2009 FBI Hate Crime Statistics report also provides a handy, and much better drawn chart:

Of the 8,336 hate crimes in 2009,

- Race-based crimes were 49%

- Religious-based crimes were 19%

- And crimes based on sexual orientation were 18%

Hate crimes have (sporadically) gone down since 1997. There has been some progress, but I admit to researching this information with the expectation of finding more progress than this. From what I can tell from these statistics, so far, hate crime legislation doesn’t seem to drastically deter hate crimes. Furthermore, many LGB victims of hate crimes who are closeted don’t report them as such. So their numbers are actually higher. Additionally, logic tells us that some crimes that might appear to be nonbiased assault and robbery are likely hate crimes in which the criminal was smart enough to keep his/her mouth shut.

But should any of this be a factor in whether or not we have hate crime laws? I don’t think so. I see this legislation as more than just punishment of criminals; I also consider it partial psychological compensation for victims of bias crimes — something that will help them in the process of healing from what’s happened to them.

Also, it is still far too early to measure the effect of the Matthew Shepard Act, especially when it comes to transgender people. The dismal 2010 statistics notwithstanding, it is not unreasonable to presume that the long-term effects of this new law will — like the civil rights law before it — reduce anti-gay hate crimes.

3. Hate crime laws — by their very nature — set up some classes of people as more valuable than others.

Many of us talk quite a bit about “bias” and “nonbias” crimes when discussing hate crime legislation, but we rarely discuss whether or not the legislation itself is biased. We shouldn’t have to have hate crime legislation. We shouldn’t. But we need it, so we have it. And we have it because we don’t make laws for the world we ought to have. We make them for the world we do have.

I don’t think that there is any argument against the statement that there are classes of people that are more at risk of bias crimes than others. For this reason, we have had some form of hate crime legislation since the civil rights movement. And even within the at-risk demographics, some are more vulnerable than others. For example, look at the percentages of the 2009 FBI statistics stated above. Crimes based on sexual orientation were 18% of hate crimes. “Given that the best studies indicate about 3% of the American population is homosexual, that means that gays and lesbians are victimized at six times the overall rate” (Southern Poverty Law Center). For this reason, we have the Matthew Shepard Act.

But hate crime laws exist to protect all people of all races, creeds, genders, and sexual orientations. The FBI collects statistics on white people, straight people, Christian people, etc. But if I’m to be intellectually honest, I need to point out that, if it’s damned difficult to prove a hate crime when it happens to an African American or a Jewish person or a gay man (and it is), how much more difficult is it to prove against — say — a white guy who was robbed by a black guy? Just look at the statistics and you’ll find your answer there.

Honestly, I think that, if we only just admitted that, yes, the inherent flaw in hate crime legislation is that it isn’t really ever going to be much help for minority on straight-white-male crime, we’d go a long way toward defusing this argument. Many thousands of people support this legislation for the ultimate societal good that it does, even though they feel that they may not be fully protected by it (no matter the stated intent). To pretend otherwise is insulting to them.

Here we’ve arrived at the familiar dilemma of the balance of competing goods.

- We approach all suspects with a presumption of innocence, knowing that sometimes the guilty will go free.

- We’ve abolished the death penalty in Illinois because we’re willing to let some horrific people live so that innocent people won’t be killed.

- We accept that the “best candidate for the job” might not always be hired and higher-scoring students might not always be admitted, so that underrepresented groups can overcome institutionalized prejudice.

- We risk having to see, and stop, some patrons from using porn on the computers, rather than allow censorship in our public libraries.

- And finally, we have laws in place that provide a harsher penalty for crimes motivated by prejudice, which likely leads to some classes having more protection than others.

These are all examples of societal goods that by their very nature cause conflict, and we accept this because the benefits that they bring to our communities outweigh the negatives that come with them. And even considering those that we don’t agree with (I don’t agree with all of them), we understand why they’re in place. We understand that there are precedents for them. We have a social contract with the most vulnerable among us that there will be laws in place to protect them.