Read Part One from Monday here.

IF YOU BUILD IT…

Opponents of the Olympian Drive project often point out that the area destined for industrial development sits on one of the three most productive soils in the world, the others being in the Ukraine and in Argentina.

That’s true, but productive does not mean profitable. For most of the first half of the 20th century, the most profitable agricultural county in the country was Los Angeles. [Today it’s probably some pot-growing county in northern California, or a southwest Kansas county with a bunch of cattle feedlots in it — it’s hard to measure.] So even productive and profitable doesn’t mean the land will be kept in agriculture, as the second half of the twentieth century in L.A. shows.

In Champaign County, it’s arguable whether agriculture, as currently practiced, is even profitable, once government subsidies are removed. Thus the notion of “it’s only farmland” meets up with the planners’ economic principle of “highest and best use.” In L.A., it was mostly subdivisions replacing farmland, as it has been in C-U.

A team of 18 persons from the local business community and local governments are now in Washington, D.C. seeking, among other things, to secure federal funding to extend Olympian Drive so that a large area north of I-74 can be developed as industrial land. Previously this group persuaded state representative Mike Frerichs to put in a $5 million line for the project in the current state capital budget, which is to be funded with video gambling [so it’s no sure thing yet].

What’s ironic is that some of the proponents, who are prone to squeal about the terrible federal deficit and wasteful spending, are at the trough. But that’s the nature of political kabuki theater, which we saw with the stimulus bill as Republicans condemned it, then posed for photo-ops when the checks came into their districts. That’s what passes for public debate these days. But then the goal of politicians in these times seems to be to convince the hoi polloi that they are “fighting” for them, and to confuse them so that the nature of that fight can never be divined.

WHY BUILD IT?

In the previous part of this story we focused on trucking, warehousing and shipping as the likely uses for this new industrial land. Currently, there is a lot of such use there, as Champaign County Economic Development Corporation CEO John Dimit noted in pointing to the Atkins Group Apollo Industrial subdivision as a model of economic development. Beside that development, which includes a major grocery warehouse/distribution center and a Fed Ex trucking center, SuperValu Grocery systems has an operation on N. Lincoln in Urbana, as does UPS.

So why not expand upon this? There is logic to it. The land is relatively cheap (it’s only farmland, after all), and it’s located at major north-south and east-west interstates, plus the I-72 line to Decatur, Springfield, Jacksonville, Hannibal, Mo, and maybe someday beyond.

On the other hand, from a regional perspective, isn’t Effingham better positioned since it straddles I-70, which basically runs from the east coast to Los Angeles (along I-15 from Utah)? C-U could then have a regional trucking warehouse facility connected to Effingham. It could be built at the Curtis Road interchange with I-57. A great advantage would be proximity to Willard Airport. This sounds like a great idea. Let’s run it by the people in southwest Champaign and see what they think about some economic development in their neighborhood. It could mean jobs for their children, and the noise and air pollution wouldn’t be that bad.

Putting that little fantasy aside, the current site has advantages. Trucking/warehousing, since it can be located almost anywhere along the Interstate system, is an extremely competitive business — so margins are critically important. What firms seek is shaving seconds and miles off their runs, and pennies off their labor cost. It is, like many if not most enterprises, a race to the bottom. C-U offers existing Interstate connections, and has been historically a low wage area in the region (largely due to the student population), so that working-class warehouse jobs will pay less than elsewhere. The location is also prime in the sense that except for a few farmers, there is no opposition to the project. And there will be no opposition from a generally compliant press and self-satisfied public.

So there are strong reasons to go forward with this project. What’s notable is that this discussion, about the real thinking behind the project, never reaches the public. Instead we get strange justifications that just don’t hold water.

THE WEIGHT OF THE ANCESTORS

This reason posits that all previous investment in time, effort and money was obviously well spent and must be redeemed. On the other hand, you might see it as institutional inertia. Or as someone once wrote in a slightly different context, “The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.”

The essence of this argument is that the road has been envisioned since the 1960s, so thus it must be a good idea. When the project came before the Urbana City Council, councilor Heather Stevenson commented that it should be approved because of all the time and work put into it by dedicated staffers. This is not a sufficient reason to support a project. Lots of work by professional, smart people, the best and the brightest, went into developing the Viet Nam war, for example.

Champaign Assistant City Engineer Dave Clark said, “A road of this magnitude and length and expense, it just doesn’t happen overnight. You have to do a lot of planning.” That’s certainly true, but this has the sound of “Call now, supplies are limited!” And it doesn’t amount to a justification for this project.

One of the point men in promoting the project is Habeeb Habeeb, a financial consultant and a spokesperson for the Champaign County Chamber of Commerce. In recent testimony, he said that planners a generation ago foresaw the need to improve Duncan, Windsor and Curtis roads on the outskirts of Champaign-Urbana. There’s no doubt that those roads have allowed and are allowing sprawl, or growth if you must, but the question is whether the assumptions behind widening and paving those roads still hold.

Of course when this project was first conceived, cars had fins, there was a large military base just north of Urbana, and gasoline was a quarter a gallon. So since we’ve been looking at this road scenario for half a century, it has to be a good idea, right? Well, suburban sprawl has been accepted and encouraged since the 1960s, too. At what point should it end, or should it end?

THREE-CARD MONTE

There is a certain sleight of hand in the argument that the Olympian extension is to serve future growth in the area, even thought that future growth is the result of the project.

Urbana Public Works Director Bill Gray has said that the road is needed to handle future growth and to relieve congestion on I-74. Since there is no congestion on 74, one wonders what he is talking about. Project documents say the connection is “critical for supporting the expected growth along the northern boundaries of Champaign and Urbana.” Dave Clark said, “The city’s growing, the community’s growing,” adding that city planners recognized that growth as early as five decades ago (see “weight of the ancestors,” above).

“Your job is not to think about what we need tomorrow,” Habeeb lectured the Urbana and Champaign city councils. “Your job is to think about what we need tomorrow and the next day and five years later and 10 years later.” That’s good advice, but that doesn’t mean that this road should be built.

The thrust of this barrage is that we must prepare for the inevitable natural growth and concomitant congestion in the area.

A more transparent view is what Mark Dixon, the Atkins Development Group’s project manager said in the News-Gazette a few years ago, “Growth north of Interstate 74 will surge once Olympian Drive is constructed and links major community arterial streets to the interstate highway network.” And as one document states, the region is more likely to attract economic growth with a completed Olympian Drive.

This area has not grown as much as you might think. Since 1970 the population of the county has gone up by less than 19 percent total. That is a pretty modest growth rate. What has grown faster, however, is the amount of space and land each of us takes up — bigger houses, bigger big box stores, bigger roads, and the rest of sprawl.

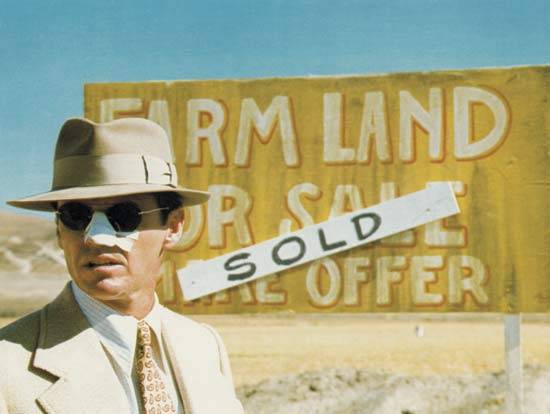

CHINATOWN REDUX

All of this is not to suggest some conspiracy by a secretive cabal of shadowy characters to enrich themselves in a real estate deal. Still, when a spokesperson for the Chamber of Commerce says, “We’re not going to engage in public debate on Olympian Drive,” one’s eyebrows arch. The sense of secrecy and misdirection is probably due less to a Chinatown scenario than a couple of other things. One is the difficulty of getting any major project done in a community that has an inane number of government entities and processes. The other is a complacent media that is more lapdog than watchdog when it comes to issues like this. In conjunction with this is a prone public beset by anomie and narcissism. But those are issues for another opinion column.

All of this is not to suggest some conspiracy by a secretive cabal of shadowy characters to enrich themselves in a real estate deal. Still, when a spokesperson for the Chamber of Commerce says, “We’re not going to engage in public debate on Olympian Drive,” one’s eyebrows arch. The sense of secrecy and misdirection is probably due less to a Chinatown scenario than a couple of other things. One is the difficulty of getting any major project done in a community that has an inane number of government entities and processes. The other is a complacent media that is more lapdog than watchdog when it comes to issues like this. In conjunction with this is a prone public beset by anomie and narcissism. But those are issues for another opinion column.

In a different way, this is less a Chinatown conspiracy than what might have once been called class-consciousness, in the sense that this public/private partnership is one of business interests and local officials who share certain assumptions about the world. These assumptions are widely shared through most of our polity, but given our current position, it’s time to question them, and propose some new ones, especially about resource use and development.

Chinatown was about one of the four indispensible resources: water [the others being soil, atmosphere and energy]. It’s something that we here in C-U have been blessed with, at least so far — no one really knows the state of the Mahomet Aquifer upon which we depend. In the west, water is still the constricting resource, and it’s something that will someday affect us here, even half a continent away.

Part One of this article spent a fair amount of time looking at California, L.A. in particular. That was partly for comparative purposes, (L.A. is always useful as a dystopia against which to compare things). L.A. is often seen as an example of terrible resource use, environmental destruction, and an unsustainable infrastructure that dooms it — the social/ecological collapse scenario of more than a few disaster movies.

Part One of this article spent a fair amount of time looking at California, L.A. in particular. That was partly for comparative purposes, (L.A. is always useful as a dystopia against which to compare things). L.A. is often seen as an example of terrible resource use, environmental destruction, and an unsustainable infrastructure that dooms it — the social/ecological collapse scenario of more than a few disaster movies.

But much of that high-tech stuff we amuse ourselves with, and skads more thingamajigs, are coming to us from Asia, through the port of L.A., and that supports much of L.A., which demands more and more water. That’s water that ends up more expensive to farmers, or even unavailable in some instances, which is why large swaths of the San Joaquin Valley have gone fallow, orchards uprooted, and fields unplanted.

———————————————————————

Most of your fruits and veggies, nuts, avacados and such come from California, especially if you’re buying organic. As Common Ground Food Coop Manager Jacqueline Hannah recently said, our local co-op has one of the lowest percentages of local foods in the country because they just aren’t available enough here. That’s more than ironic, when we live amidst one of the three most productive soils in the world.

Most of your fruits and veggies, nuts, avacados and such come from California, especially if you’re buying organic. As Common Ground Food Coop Manager Jacqueline Hannah recently said, our local co-op has one of the lowest percentages of local foods in the country because they just aren’t available enough here. That’s more than ironic, when we live amidst one of the three most productive soils in the world.

L.A. looks the way it does because it was born at the dawn of the age of petroleum and grew up in it. In some ways, the same can be said for C-U, and all the other places in the world connected by highways and freighters.

We’re approaching the sunset of the petroleum age now. In a future column, I’ll look at the possibilities of an alternative type of economic development that is less dependent on growth for growth’s sake, and profligate resource use and abuse. Something instead of projects like Olympian Road.