Matt Talbott is a man who understands the idea of rock n’ roll. It would be impossible to write the majority of HUM’s songs without understanding Led Zeppelin, eighties metal, punk rock, The Pixies, and so much more. But Talbott clearly does not understand playing the part of “rock star.” While an entire generation of musical peers in the 90s just pretended like they did not want to be famous, Talbott clearly did not want that part. HUM ended up being successful as part of a happy accident of time in which four guys playing rock music on their own terms could achieve a fair amount of success in spite of not really seeming to care about the rock ‘n roll mystique. So now it is 17 years later and Talbott seems flumoxed about why anyone would be at all interested in interviewing him about his band’s second album.

Matt Talbott is a man who understands the idea of rock n’ roll. It would be impossible to write the majority of HUM’s songs without understanding Led Zeppelin, eighties metal, punk rock, The Pixies, and so much more. But Talbott clearly does not understand playing the part of “rock star.” While an entire generation of musical peers in the 90s just pretended like they did not want to be famous, Talbott clearly did not want that part. HUM ended up being successful as part of a happy accident of time in which four guys playing rock music on their own terms could achieve a fair amount of success in spite of not really seeming to care about the rock ‘n roll mystique. So now it is 17 years later and Talbott seems flumoxed about why anyone would be at all interested in interviewing him about his band’s second album.

I’m not sure the 35-year-old version of me understands why I should write about HUM either. After all, I briefly played on a terrible rec league basketball team with a member of the band. And I have heard stories about how Talbott likes to practice his golf swing in between takes at Earth Analog recording studios. Not exactly the stuff of sequestered rock legends.

But the 17-year-old version of me gets it. In May of 1995, I drove down for WPGU’s Planetfest out in the cornfields of east Urbana on a mission to see a band that had released You’d Prefer an Astronaut 45 days earlier. As HUM blew the place up right after a bunch of wannabes in an MTV buzz band called Wax, I was left with an impression that simply can not be erased despite years of cynicism. Though they may be four fairly unassuming who guys who shun attention offstage, on stage, HUM are undeniable rock stars.

Prior to Electra 2000, HUM had rotated through several different lineup changes, releasing their debut album Fillet Show, which is basically an album by an entirely different band. But after original main songwriter Andy Switzky left the band and Talbott took over the role of head song guy, they came around to the lineup of Talbott, Tim Lash, Jeff Dempsey, and Bryan St. Pere. Though the band had several iterations prior to that lineup, Talbott says that by the time they recorded Electra, the band was “locked and loaded.” From the opening notes of “Iron Clad Lou,” it’s clear that Talbott’s description is apt. The album is blistering testament to the power of dynamics and heavy 90s rock n’ roll, taking a few breaths of air now and again, but mostly just plowing through with an unparalleled intensity.

And Electra 2000 came out during a very good time for the band, considering that major labels were on the lookout for the next big thing in college towns throughout America. Several local bands were on, or were about to sign, major label deals around the same time (Poster Children, Mother/Menthol, Hardvark). Local promoter/brief HUM tour manager Ward Gollings explains that bands at that time just assumed that is how things always worked:

It is bizarre in retrospect. But at the time I think it just seemed natural to many of us. Good bands were doing good things and they started getting the attention they deserved. Hard work and all of those shitty $50 shows playing to 14 people and a dog finally paying off.

Electra’s strong songs and the band’s live performance brought the interest of at least a couple major labels.Talbott confirms the band enjoyed a fairly stereotypical major label signing experience, which included trips to NYC and L.A. for wining and dining. He describes the whole process as an exciting and fun time for the band. Eventually they decided to go with RCA:

We started getting interest pretty shortly after Electra came out. It took a year or two after those conversations began before we signed. We specifically chose RCA because they didn’t have bands like us on their roster. Our thinking, and I still think it was correct, was that if there was anyone at the label who was into our style of music, we’d be the only game in the building.

In a music scene as insular and incestual as Champaign-Urbana, it would seem that there was bound to be some resentment over HUM getting a record deal. Though the Poster Children were already on a major label and two other bands eventually got deals, HUM seemed like it made the biggest splash. Despite this, Talbott did not see any backlash:

I suppose it’s very possible that there were those who didn’t think we were any more deserving of a record deal than other bands. I would probably have agreed with them. But I never experienced any open resentment.

After touring extensively for Electra and road-testing new songs, the band felt good about going into the studio to record their major label debut. The band recorded a version of the album that did not go as well as they hoped, so they enlisted Keith Cleversley to remix the sessions. Cleversely, who had a buzz around him after producing The Flaming Lips’ breakthrough album Transmission from the Satellite Heart, convinced the band that they might be better off completely re-recording much of the material:

Keith had just opened a new studio in Chicago, and we were big fans of the work he’d done with The Flaming Lips. We had started this record at another studio. But the sessions did not go well and we were not confident in what we had. I do recall bringing the rough mixes to Keith and sitting down with him to listen together. We talked at length about each song. He’s a pretty straight shooter so he shared with me what he liked about some songs and felt was lacking in others. We parted ways agreeing that starting from scratch might be our best bet. He wasn’t really dogging what we’d done. In fact, he had some very kind words to say about certain parts of the record. The recording of “Boy With Stick” (a B-side from that era) is from the sessions we did before hooking up with Keith. It’s huge sounding. A great snapshot of that tune. I love it, and Keith thought it was a great recording. We tried to better it during our sessions with him and could not.

From the first swirls of “Little Dipper,” it’s obvious that the additional sessions with Cleveresley were well worth it. While Electra 2000 had built the foundation of HUM’s sound: dynamics, unusual guitar tunings, vague lyrics about relationships/space, pummelling drums, and an amalgamation of punk, metal, and more, Astronaut importantly throws swirling guitars and studio time into the mix.

On Astronaut, HUM was no longer content to work from the same “throw the hammer down” formula that dominates Electra. The songwriting improved and the band used their instruments in new ways. For example, instead of just driving each song along, the bass guitar comes in and out of the mix, building momentum, but also changing the directions of songs. On “Why I Like The Robins,” it bounces and sends the song in an unexpected direction, adding a nice counterpiont to the guitars near the end.

HUM were clearly meticulous in recording Astronaut, so much so that Cleversely spends a great deal of time describing the guitar sounds of Astronaut on his website: “What HUM did on almost every track on the record is triple-track their guitar tracks. One of the most amazing things about Tim Lash was his ability to exactly duplicate his performance, no matter how complex… As soon as they got a performance that they were happy with, they immediately recorded a 2nd and a 3rd track of guitar.” When asked about the changes that came on Astronaut and the recording process, Talbott describes time and money as playing a role, but explains that detailed studio work was always a band trademark:

Well, it probably has to do with there being more time/money to make a more layered, dense recording. Those songs were, for the most part, written long before we went into the studio, and we toured a great deal between the recording of Electra and Astronaut. Our band was made up of four guys who were extremely meticulous and extremely opinionated about our writing and our recording. To speak to your specific example, there was some layering of guitar parts to add density and heft to some of the arrangements. But that’s not a technique unique to us in any way.

You’d Prefer an Astronaut was a major step forward in terms of creating a cohesive album. The nine tracks meld neatly into each other and flow in a way that few bands can ever pull off:

That’s certainly what we were going for. I’m sure there was all kinds of arguing and gnashing of teeth over the order. “The Old Man” came from the other (pre-Cleversley) session. And it was kind of a little throwaway song anyway. Its purpose was to give the listener a little break. Whether it accomplishes that in a positive way, or if it’s just a waste of space and the album would have been better served by an additional, more fully realized song might be a legitimate question.

HUM’s lyrics are famously obtuse and focus on space and distance. And trying to read too much into any one phrase or idea might give the listener the wrong idea. As Talbott explains, “the song ‘Suicide Machine’ is about a couch. It’s all metaphors, man.” But overall, I do not think Talbott gives himself enough credit when he claims, “I pounded away at a few themes a little more than I should have. I probably could/should have backed off on all that space shit.” Whether it’s intentional or not, Astronaut holds up lyrically because there is a theme of love, loss and the way small issues can make distances seem insurmountable. They may be metaphors, but space, time, and death are powerful symbols. Add to that the real vignettes he weaves into the songs and 17 years later, the album still connects.

Talbott is at least willing to relent that a heroine who seems to be the focus of many of the songs is a real person. He admits that “some version of my wife makes a few guest appearances.”

Though Astronaut contains many excellent songs, only one of the songs actually made a dent on the modern rock charts. To modern C-U ears, the song probably seems overplayed, but at the time, “Stars” was revelatory. It uses HUM’s dynamic formula in a rare way, and the slow build seems to add more guitar lines than seems possible. After being released, the song started to get airplay on modern rock radio across the country. Its riff is nothing short of iconic, and the build at the end should probably just go on forever. Ward Gollings remembers the song’s video:

I remember they had already done a video for the song with a friend in Jeff’s basement at the corner of Randolph and Stanage. It was a full-on production, albeit for 1/10th of what most videos were shot for at the time. MTV wanted to make the song a “buzz bin” video, but the band refused to make another version with a big time budget/producer.

Despite sticking with the original video, “Stars,” still brought the band a fair amount of success. Suddenly, four dudes who had formed a band to play around for their friends were playing MTV’s 120 Minutes, Conan, The Jon Stewart Show, and, most famously, on The Howard Stern Show. In recent years, the song has had a resurgence, selling tens of thousands of digital downloads, mostly due to its placement in a Cadillac commercial.

Unlike many artists who seem to get sick of their biggest hit, Talbott still likes the song and considers it one of the better HUM songs.

I think that, in terms of our songs, it’s a good one. We got great response from it when we played it locally. (I remember one time a friend of mine split his head open on my guitar at a party we were playing, and he asked if we’d please play “Stars” before he headed off to the hospital.) But we were certainly surprised at its commercial success. I think the label was too.

Touring behind an altnernative rock hit took the band pretty far, and they became a touring Champaign band that, according to Gollings, could actually play for packed crowds:

“Stars” had caught on and there were more fans coming to the shows for sure. They were a bona fide headline act that was consistently filling 500-capacity venues. The album came out in April 1995, and I assume they a couple two-to-three week tours of club shows that spring/summer, but I can’t quite recall a particular leg. They had a side stage slot at HFS Festival at RFK Stadium in June. They did a week or so opening for The Verve in late July, followed quickly by a five-show stint on side stage of Lollapalooza in mid-August. Then, for the entire month of September 1995 they opened for Bush, which was sold-out 3,000–6,000 capacity shows. After that they took a lengthy break (to be home with friends/family) until February 1996 when they did 23 shows in 23 days with Mercury Rev as co-headliner/opener. It was definitely an exciting and memorable era.

At the time, it probably seemed like every semi-alternative band with a hit should have moved a million albums, but HUM never was an easy sell. They were not nerdy enough to be Weezer, not particularly edgy enough to fit in with the Tool and NIN fans of the world, and they certainly didn’t fit into the neat college rock template established by REM. They hated doing interviews (and still do, I might add). Still, over 250,000 people bought You’d Prefer an Astronaut. That’s an amazing number of people. In hindsight, it may disappoint many of the band’s fans on the internet, and it was probably disappointing to the label. But Talbott is still amazed:

I think that when you start a band in your basement in Champaign, IL with your long-term goals including getting a gig at Mabel’s on maybe a Thursday night, and then you do your thing for five or six years and are still playing to fewer than 50 people most nights of the week, that eventually selling 250,000 copies of a record is kind of mind-blowing. I’m still not convinced it happened.

And unlike many bands that experienced initial success and then retreated, Talbott does not seem bitter to RCA, nor does he feel like he was taken advantage of:

I was mostly OK with the process. As far as major label experiences go, it was probably as good as it gets for bands like ours. They did their best to try and understand us, and I can’t think of many times where creative control of the music and the message was not in our hands. There were certain things I hated doing (videos, interviews [no offense!]), but otherwise it was no big deal. We had a song on the radio, people were coming to our shows, and we’d always get a free meal anytime we were in NY or L.A. I mean, my god. It was a blast.

After the success of “Stars,” the label was unable to procure any more “hits” from the album. The band then took a significant amount of time to record their follow-up album Downward Is Heavanward. And though many HUM fans consider it the superior album, the album failed to make the same impact as its predecessor, selling a very modest 30,000 records. Gollings explained that timing is key:

I think RCA was happy to sell 250,000 copies of Astronaut. But without a doubt they wanted 500,000 (gold), or better yet a million (platinum). The guys did not want to spend months upon month on the road though, which is what that would have required essentially. I think for “Stars” (and Astronaut) they just happened to be in the right place at the right time. The A&R guy who signed them had just signed Dave Matthews Band a year or so earlier. A kick-ass entertainment lawyer saw them at CBGBs and loved them. A future big-time booking agent saw them at SUNY Binghamton when he booked the Poster Children. The guy who managed Jane’s Addiction took them on as a client. Everything somehow came together, the stars all aligned and they were surrounded by a ridiculously great team of people. And they were an incredibly amazing live band of course. When they would launch into “The Pod” (typically 2nd on the set list), it was like their soundman was hitting some sort of “turbo” button as I blasted the strobe lights. You couldn’t help but be blown away and become enamored by HUM. But three years between singles is a pretty long time in the music industry. Tastes change and times change. I think the bands who have another hit single are lucky. It is perhaps one of the hardest things to do, following a “hit” record with an equally big “hit” record.

Though Talbott consistently denies the band has much of a legacy, it seems like their mystique has only grown since they called it quits in 2000. The production and tunings from Astronaut and Downard certainly seem to be present on a lot of later 90s albums. The guy from Deftones calls Astronaut a major influence, and, as mentioned earlier, Cleversley even has a special studio secrets page on his site titled “HUM guitar sound.” Still it is hard for Talbott to place HUM in the larger spectrum:

That’s a tough one for me, because the music I like the most, whether it’s music of that era or later, is in no way influenced by us or that record. That’s why I am reluctant to pat ourselves on the back too much.

With vinyl copies of Astronaut going for $250 on eBay and bands like Sugar re-releasing their 90s albums, fans want to know when HUM will follow the trend and release a remastered version of the album with all the extra goodies. Unfortunately, Talbot’s current plans to raid the band’s discography are quite limited:

I have about 300 copies of Astronaut on vinyl. They are all warped. I need to unwrap each one individually, flatten it with this record flattening thing I bought, and then re-shrink wrap. Then they’ll be available at earthanalogrecords.com. Stay tuned.

When I ask Talbott how he feels about Astronaut and if there is anything he would change, he is forthright:

I don’t really think that way, so it’s hard for me to answer that one. Even the worst moments of my life I wouldn’t wish away. All of it, our decisions, our experiences, our expressions, makes us who we are, and I don’t want to be someone else. I will say it’s as good a record as we could have made at that time.

And it’s as good of a record as just about anybody made at the time. Astronaut is among the best albums ever to come out of Champaign-Urbana. And barring some miracle, I doubt any local band can ever match the second half of the album, which, to me, is the absolute gold standard for what a “side” of a record should sound like. Starting off with my personal favorite “Why I Like The Robins,” those four songs basically run the gamut of what makes HUM such a great band. How many artists could successfully go from screaming, “You’re a waste of a song” to unironically singing, “A love song to everyone I know, arms wide open, here we go” within a span of three songs?

If you’re a fan of the band and the dichotomy of their music, those last lyrics are the ones to hang your hat on. Talbott and the rest of the band might not have cared about the industry or becoming rock gods, but they clearly are touched and honestly care about their passionate fan base.

Some other quick hits from Talbott:

As a child, were you interested in space travel and astronomy? Where did these themes come from? Was it just a reaction to the sound of the music?

I suppose I was. And I grew up in the country. I spent most all of my time outside. We lived in an area where there was unlimited access to forest areas. So that’s where I spent my time. I think my emotional connection with our larger, natural world is thus important to me as a person and as an artist. I know that sounds like a bunch of arrogant bullshit, but I’m just trying to answer the question as best I can.

How do you feel your band would do if it was just coming up in today’s musical landscape?

That’s an interesting question. I’ve kinda wondered about that and really can’t say. I think it’s very likely we were in the right place at the right time.

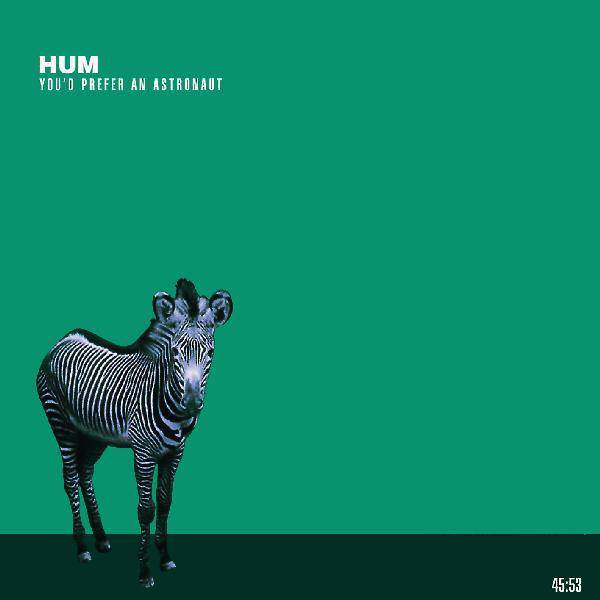

What about the cover of You’d Prefer an Astronaut?

I think it’s great. Iconic and lonely. Our friend Andy Mueller came up with it, using some photos we provided. We all loved it right away.

Everyone seems to come back to your performance on Howard Stern, but of all the things you went through during that time, what was the most bizarre/interesting?

Well, that would rank up there for sure.

All modesty aside, what did it feel like to know your song/video was getting airplay all over the States and in several other countries?

Much like when my favorite sports team wins, it made me feel superior to others.

What was it like to be placed in MTV’s infamous Buzz Bin?

Like getting shit out of the bottom of the Miami porn industry.