This pocket of the Midwest has a jewel of an institution tucked away in its folds. Among the cows and corn fields, there is a haven of both exotic culture and raw, everyday experience. The Krannert Center for the Performing Arts is a building you’d expect to find in Chicago, perhaps Indianapolis. But there it is: affordable, accessible, impossibly rich in opportunity, and down the street from my house.

I’ve been going to Krannert for over twenty years. Thanks to boundary-pushing teachers and an astounding youth outreach program, I’ve seen everything from African drum circles to Russian ballet companies to Japanese theatre groups. When I walked into The Great Hall, I did it as a seasoned veteran; the familiar sights and sounds took me over as I opened my program to see what was in store for us that evening.

Full disclosure: The U of I Symphony Orchestra had the misfortune of playing exactly 24 hours after I saw ECCO (the East Coast Chamber Orchestra), a group that changed the way I view and think about string ensemble performances. ECCO played in the same hall the previous night; I even sat in the same chair. My fiance and I had gotten tickets on a whim. I was tired after a long day at work, but I’m always up for a new experience. Why not? Intermission is a reliable escape hatch…

Unlike most other string ensembles, ECCO is run in a democratic fashion. No one is in charge. There is no conductor and the group decides together on selections for each performance. The section leader rotates after every piece; only cello and bass players sit. I’ve never seen a string ensemble play that way, although I understand it’s not unheard of. In this construct, every player engages with every other player, taking his or her cues from the expressions and movements of the surrounding musicians. The result is fantastic. This group plays as one violin, one cello, as a single bass. They do not compete for a listening ear, but blend to make a seamless, exciting, and soothing sound that fills its space. They enjoy themselves, and it’s obvious. After the first movement, it was clear that there would be no trudging off to bed at intermission.

The next night, in the same seat, still buzzing from ECCO’s performance, I looked at the U of I Symphony Orchestra’s program. I was pleased to see Mozart at the top of the list. Who doesn’t like Amadeus? I love to hear it, love to play it, and The Magic Flute is, of course, delightful. We were off to a good start.

The next night, in the same seat, still buzzing from ECCO’s performance, I looked at the U of I Symphony Orchestra’s program. I was pleased to see Mozart at the top of the list. Who doesn’t like Amadeus? I love to hear it, love to play it, and The Magic Flute is, of course, delightful. We were off to a good start.

The overture to The Magic Flute was, at turns, light and bouncy and a warm, soothing hand, just as it should be. I was overwhelmed with childhood memories throughout. As a young violinist, I was obsessed with Mozart and Beethoven, listening to the young prodigy in my father’s truck during the day and soothing myself to sleep with the deaf composer’s work by night. The magic of the flute was as effective that night in The Great Hall as it was when I heard it in my youth, the first of fifty times.

The orchestra’s next selection was by Paul Maurice, an arrangement of five movements led by an alto saxophone. The soloist, Phil Pierick, a doctoral candidate at Eastman School of Music, took the stage with the smooth, experienced confidence of a young man at the top of his game. Maurice’s Tableaux de Provence was guided by musical director Donald Schleicher and Phil Pierick with assured leadership and thorough musical ability. Mr. Pierick is a true talent, maneuvering time signatures, tempos, and key changes with effortless technique. Before Friday, I had seen orchestras led by pianists, flutists, tenors, sopranos, and violinists, but never a sax. The buttery notes Pierick fed the audience were the result of unapologetic patience. This was the work of a musician who knows that some notes should hang, to develop and sink downward, while others require a light, brief touch, like a hand testing the heat of an iron.

The orchestra’s next selection was by Paul Maurice, an arrangement of five movements led by an alto saxophone. The soloist, Phil Pierick, a doctoral candidate at Eastman School of Music, took the stage with the smooth, experienced confidence of a young man at the top of his game. Maurice’s Tableaux de Provence was guided by musical director Donald Schleicher and Phil Pierick with assured leadership and thorough musical ability. Mr. Pierick is a true talent, maneuvering time signatures, tempos, and key changes with effortless technique. Before Friday, I had seen orchestras led by pianists, flutists, tenors, sopranos, and violinists, but never a sax. The buttery notes Pierick fed the audience were the result of unapologetic patience. This was the work of a musician who knows that some notes should hang, to develop and sink downward, while others require a light, brief touch, like a hand testing the heat of an iron.

Pierick’s only downfall was the race he seemed to be in with the rest of the players. They met often, but rarely stayed together for one purpose very long. After the previous evening’s inspiring collaboration, I found myself physically aware of the disjoint.

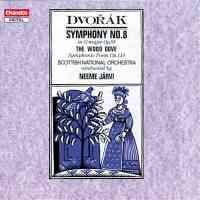

The evening ended with Symphony No. 8 in G Major, Op. 88, by Antonin Dvorak. The second movement, Adagio, lulled me to sleep, and I mean that in the best possible way. (I’m a sucker for “adagio.” It’s a lullaby, just to say it.) The fourth movement, Allegro ma non troppe, was the most technically difficult movement. It featured several tempo and time signature changes at a breathless pace, which left the audience impressed, at least in my corner.

The evening ended with Symphony No. 8 in G Major, Op. 88, by Antonin Dvorak. The second movement, Adagio, lulled me to sleep, and I mean that in the best possible way. (I’m a sucker for “adagio.” It’s a lullaby, just to say it.) The fourth movement, Allegro ma non troppe, was the most technically difficult movement. It featured several tempo and time signature changes at a breathless pace, which left the audience impressed, at least in my corner.

After seeing something the previous evening that literally changed my mind, I did not expect to find anything enjoyable about the traditional style of college musicians, no matter how proficient. (I’ve found, especially in those 24 hours, that my expectations don’t amount to much.) I saw diligent, talented players who haven’t yet survived the personal experiences that shape a craft. They are skilled, yes, but eager to please, still focused on perfection instead of emotion. I will end this assessment with the statement I made the night of the performance: There are some future professionals in there. They’ll be great, once they get shit on a few times.