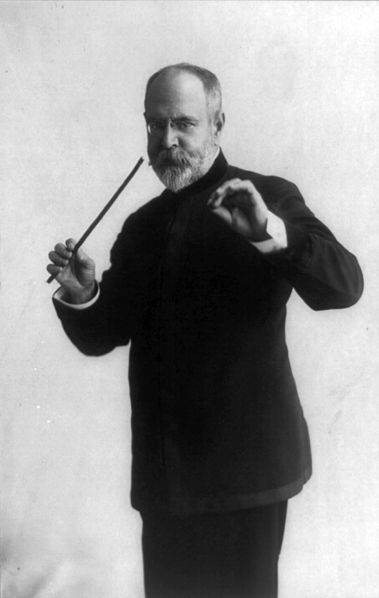

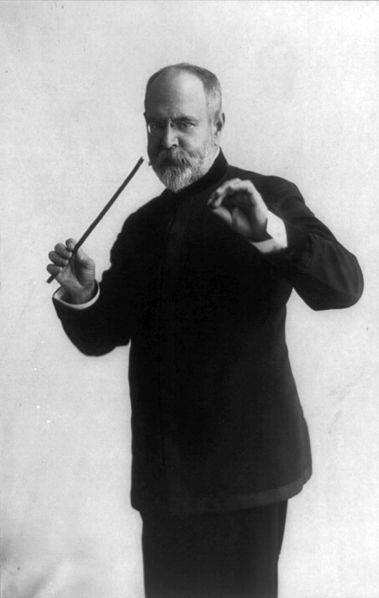

Want to know more about John Philip Sousa’s performances in England during the early years of the Twentieth Century? Then check out the exhibit A British Tar: John Philip Sousa’s Anglo-American Connections, which is currently being shown at the Sousa Archives and Center for American Music at the University of Illinois. It features original and published music manuscripts, programs, and a photograph pertaining to the Sousa Band’s highly successful visits to England on four overseas tours between 1901–1909, as well as its 1910–1911 World Tour. The exhibit will run for nearly a year, and was created by UI Assistant Archivist for Music and Fine Arts, Adriana Cuervo.

Want to know more about John Philip Sousa’s performances in England during the early years of the Twentieth Century? Then check out the exhibit A British Tar: John Philip Sousa’s Anglo-American Connections, which is currently being shown at the Sousa Archives and Center for American Music at the University of Illinois. It features original and published music manuscripts, programs, and a photograph pertaining to the Sousa Band’s highly successful visits to England on four overseas tours between 1901–1909, as well as its 1910–1911 World Tour. The exhibit will run for nearly a year, and was created by UI Assistant Archivist for Music and Fine Arts, Adriana Cuervo.

Why tour England in 1910?

I spoke about the exhibit recently at the Sousa Archives and Center for American Music with UI Archivist for Music and Fine Arts and Director, Scott Schwartz. One of the items in the exhibit is a program from a British concert, and Schwartz explained some of what made England desirable to John Philip Sousa as a touring destination to begin with:

For the band’s 1910–1911 World Tour, the Sousa Band travelled around the world for 352 days. The band performed exclusively in English speaking countries. He had a strong connection with the Brits. Arthur Sullivan’s H.M.S. Pinafore was premiered in 1878 and became an instant success in Britain, and Sousa quickly produced his own arrangement of this comic opera in the States in 1879, without Sullivan’s approval. However, when Sullivan attended Sousa’s performance he told him that his version was particularly good, better than most. In some respects, while we think of Sousa as the “March King,” in reality he had a great affinity for theatrical drama; he had a strong love of theater. He often borrowed from and imitated those composers he has great respect for, and several, like Sullivan, came from Great Britain. So he has this connection.

How did Sousa write his music scores?

The exhibit features the original holographic scores for two Sousa compositions, Imperial Edward March, from 1902, and Hands Across the Sea, from 1901. You can see Sousa’s handwriting on the music pages. I asked Schwartz how Sousa approached writing scores — did he always work the same way, or did he mix it up? Schwartz responded:

As with most composers, Sousa’s approach to each piece varied. Sometimes he would create a piano sketch first and then follow up with a full score and parts for either band or orchestra, and at other times he would craft a full band score first. For his Stars and Stripes I believe the piano sketch actually came first and then he did the full band arrangement next. Then you’ll have examples where he begins to pull together thematic fragments into a single work, like he did for his operetta, The Irish Dragoon.

Did he approach music composition like a fictionalized Mozart where he wrote out every piece perfectly on the first attempt? No. Was his approach more like Beethoven who constantly changed and revised his scores many, many times until the working original copy was nearly impossible to read? No. I guess the best way to describe Sousa’s compositional process is that it was a little of both at times. Sometimes he’d write out a rough piano sketch and then create a set of band parts from it, and sometimes he’d create a full score and then create the piano score from that, as well as arrangements for many other different instrument combinations, for example Stars and Stripes for mandolin duet, piano four hands, and harmonica. There are lots of different ways to skin the musical cat and he used them all.

From London to Paris (Illinois)

One of the exhibit items is a photograph of the Sousa Band performing at the Crystal Palace in 1901. While Sousa played in London and other great cities of the world, Schwartz explained to me that he was also comfortable doing gigs in much, much smaller communities, including a nearby one — Paris, Illinois:

One of the exhibit items is a photograph of the Sousa Band performing at the Crystal Palace in 1901. While Sousa played in London and other great cities of the world, Schwartz explained to me that he was also comfortable doing gigs in much, much smaller communities, including a nearby one — Paris, Illinois:

When we think of his impact, we have to remember that most small-town communities in America had a community or regimental band, not always well rehearsed or able to play the great Western European music literature of the time. He was able to take what we think of as western art music and bring it to these small communities — communities like Paris, Illinois — and play entertaining concerts in a way that was “Sousa-esque.” He brought that great music, which was performed by his highly-skilled bands, to communities that may have never had that opportunity to be exposed to that genre of music. Yes, he also played in Chicago, New York, San Francisco, other cities that had their great orchestras, but he wanted to let folks know that a great wind band was equal to any string orchestra.

In conclusion

From researching Sousa on the web for this article, I learned that the Sousa Archives and Center for American Music at the UI is one of the best places for Sousa studies in the world — there are links and references to UI articles and exhibits everywhere. I visited this particular exhibit twice, and having archivists Cuervo and Schwartz set aside what they were doing to give detailed answers off the top of their heads to whatever questions I asked them, proved that the Center is a great place for even casual enthusiasts to get their Sousa on.