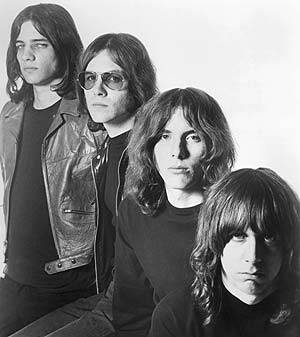

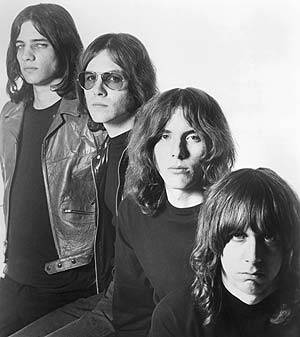

I was at work last week when my friend and C-U rock alum, David Landis, e-mailed me the sad news that legendary Stooges guitarist Ron Asheton (left) had died at the age of 60, reportedly of a heart attack. I am not a fanatical Stooges fan, so it wasn’t one of those “where were you when you heard the news” moments, but it did lead to a lengthy e-mail exchange that got me thinking about guitar playing “style” and the ways our urge to categorize and name things invariably limits our understanding of that style.

I was at work last week when my friend and C-U rock alum, David Landis, e-mailed me the sad news that legendary Stooges guitarist Ron Asheton (left) had died at the age of 60, reportedly of a heart attack. I am not a fanatical Stooges fan, so it wasn’t one of those “where were you when you heard the news” moments, but it did lead to a lengthy e-mail exchange that got me thinking about guitar playing “style” and the ways our urge to categorize and name things invariably limits our understanding of that style.

If you don’t already know who David Landis is, I should tell you right now that I believe he deserves a star in the C-U Rock and Roll Hall of Fame for many reasons. A fantastically gifted graphic artist, he designed covers for all of the Didjits and Lee Harvey Oswald releases, as well for other local bands. He also oversaw all of the Didjits video shoots and orchestrated the chaos that was their later stage shows (one day soon I promise to tell the story of their last appearance at Mabel’s, maybe the greatest rock spectacle I have ever seen). Additionally, he played drums on the Lee Harvey records, the latter two of which should be on everybody’s 100 Greatest Rock Records Ever list. Seriously, if you haven’t heard A Taste of Prison and/or Blastronaut, you owe it to yourself to do so soon. And perhaps most significantly in terms of the ongoing C-U music scene, he originated the Great Cover Up, an annual fundraising concert, the 18th edition of which will take place on the 18th, 20th and 22nd of this month.

Beyond that, Landis is something of a rock nut, and we get carried away every so often trying to make sense of this thing we love so much, yet can only occasionally explain to our satisfaction. Last week, he got us started with this observation regarding Asheton’s guitar-playing:

You know, from a graphic standpoint, the hardest thing to try and recreate is chaos … junk, clutter … it always looks too well placed when you try to manufacture it. Same with [Asheton’s] playing. Those first two records (The Stooges and Funhouse) … no one could really do what he did, ’cause it sounded like he didn’t know what he was doing, and it sounded amazing.

As any casual follower of punk or indie rock knows, simultaneously sounding unschooled — like one doesn’t know what one is doing — and amazing are badges of honor, the point of the whole punk exercise. Stripping away excess and virtuosity to reveal pure feeling was the essence of punk’s revolution, and Asheton was doing it naturally many years before the appellation “punk” was anything but an insult. And as Landis rightly points out, that kind of playing can’t be copied; it can’t be measured; it can’t be explained. It just kind of is.

I learned a fairly long time ago that style is as much about limitations as it is about ability, that what one cannot do profoundly influences what one does. Genius isn’t necessarily about total mastery; as often as not, especially in the fluid world of rock music, it’s about playing extraordinarily well within (or without, as the case may be) boundaries, about bringing an indescribable grace to what one does, regardless of how ragged or vicious that thing might be. Saying someone plays “as if they don’t know how to play” doesn’t mean they aren’t musical, that there isn’t rhythm and passion in their playing. It merely describes an aesthetic sense, an attitude, a privileging of sound over theory.

Let me clarify here and now that I am not talking about the arsenal of riffs, the dirty, fuzzed-out foundations of classics like “I Wanna Be Your Dog,” “No Fun” or “T.V. Eye.” Their power is undeniable, but I would argue they’re not where the real magic lies. Instead, I favor the lead parts, the wah-wahed, jagged answers to Iggy’s primal howl, the parts of the songs where things truly open up, where the band express collectively a real sense of space and groove. Riffs are great for punching the air and head-banging, no question, but the other stuff, the sections of nearly every song where the band stretches out, that’s where you’ll find true adventure and possibility. Check out any number of Funhouse tracks for examples: “Loose,” “Dirt,” “1970” and especially the epic title track. In particular, check out the Asheton/Steven Mackay (sax) double team over the choruses in “Funhouse.”

I think that’s the reason I love the Stooges (pictured left, Asheton in shades) and run out of patience with punk fairly quickly — that sense of space and infinity. If we’re not careful, all of our after-the-fact categorizing of the Stooges, of Asheton’s playing, can lead us to ignore that larger project, that sense of craziness and abandon that transcends the sledgehammer effect of the riffs themselves. The Stooges truly belong to what I call the “freak” period, that sliver of time between hippie experimentation and ’70s bombast: not quite psychedelic, not quite progressive, not quite metal, not purely hard rock, not quite or purely anything. This handful of years — let’s say 1968–1972 — produced hugely influential stuff that nevertheless managed to slip through the standard cracks of categorization, real accidents of history, unplanned revolutions that few paid attention to at the time. That’s the legacy of those first two records, of Ron Asheton, a real guitar hero, warts and all.

I think that’s the reason I love the Stooges (pictured left, Asheton in shades) and run out of patience with punk fairly quickly — that sense of space and infinity. If we’re not careful, all of our after-the-fact categorizing of the Stooges, of Asheton’s playing, can lead us to ignore that larger project, that sense of craziness and abandon that transcends the sledgehammer effect of the riffs themselves. The Stooges truly belong to what I call the “freak” period, that sliver of time between hippie experimentation and ’70s bombast: not quite psychedelic, not quite progressive, not quite metal, not purely hard rock, not quite or purely anything. This handful of years — let’s say 1968–1972 — produced hugely influential stuff that nevertheless managed to slip through the standard cracks of categorization, real accidents of history, unplanned revolutions that few paid attention to at the time. That’s the legacy of those first two records, of Ron Asheton, a real guitar hero, warts and all.

––

The Lee Harvey Oswald records A Taste of Prison and Blastronaut are technically out of print, but both are available as downloads. In 2005, Elektra released 2CD expanded and remastered editions of The Stooges and Funhouse. Both are currently in print.