“Modern opera” is an oxymoron.

Google the phrases “contemporary opera” or “modern opera” and you’ll strike derision. The most optimistic accounts urge no, really … try it.

Grand costumes and foreign languages perpetuate a perceived grandeur, but at their core, operas are silly. In the same way Vatican II ruined church’s aura for a lot of people, hearing a libretto in one’s own language dispels the illusion. Operas are trite stories.

If modern opera reflected the same depth, relative to its period, as classical Italian opera, it would look a lot like this Armando Ianucci satire.

Contemporizing the art form in the past meant abandoning its fundamental tenets. The “rock opera” is no different from any other collection of guitar, drums, and singing alba, but for the unifying storyline. Tommy and Jesus Christ Superstar are not staged by opera companies. They’re performed by rock bands, or musical theater.

Is Porgy & Bess really opera? It depends how you sing it. The songs are easily transducible to other genres. George Gershwin’s orchestral music was well on its way to jazz, and “beat groups.” (That’s why we like it so much.) Contrast We Five’s version of “I Got Plenty o’ Nuttin’,” or Ella Fitzgerald’s “Summertime.”

Strictly speaking, all “works” of staged, orchestrated, dramatic singing are “opera.” But at some point, the word’s meaning shifted. “Opera” became a vehicle for a particular style of singing. If that art form is to survive, it must appeal to modern audiences. It mustn’t confine itself to seventeenth century musical stylings, or seventeenth century musical instruments. It can’t be silly. It can’t be confused with a musical. It must convey a message that signifies something more than boy meets girl.

Enter composer Stephen Andrew Taylor.

With his new opera Paradises Lost, Taylor, a youthful Urbana dad and professor of composition, resurrected the fundament of opera qua opera, abandoning its anachronisms.

THE STORY

Marcia Johnson’s libretto, based on Ursula K. LeGuin’s original novella from 2002’s The Birthday of the World, is not science fiction. It merely takes place on a space ship. Instead, it’s social science fiction. It’s human behavioral science. To my mind, that’s much more compelling.

Specifically, it’s atheists versus believers; the foremost, beguiling human controversy of the naughties. (It’s also boy meets girl / boy loses girl, and there are some musical capitulations to the sentimentalists — but I can live with that.)

All the characters were born on a space ship. It’s the only “world” they know. Computer programs tell them they’re emissaries of a planet long left behind. Ostensibly, they’re part of a 200 year mission to seek habitable life on a different planet. Because the characters have homo sapiens life cycles, and because the story begins in year 141 of the journey, no one on the ship has personal experience of his home planet.

We learn that the believers, a religious cult called Bliss, spawned immediately subsequent to the death of the last “Zero Generation” traveler — the last woman with experience of planet-based life. The David Koresh of Bliss is named Patel. His followers are called Angels.

A puckish narrative twist finds the Angels rejecting the plausibility of Life After Trip. They don’t believe in planets. The voyage, the ship, their present reality; that’s all there is.

Stories featuring space ships are generally billed as science fiction. Most are fantasy. The difference is that science fiction describes, in detail, systems and processes that don’t exist. Paradises Lost describes nothing scientifically. We never learn how the travelers’ propulsion engines work. We don’t know how they convert human excrement to food. The only nod to science is a “gravity sink” that warps time, thus abbreviating the journey by 20%.

In the end, the crippled, elderly boy gets widowed, matron girl. The atheists get the gritty, unpleasant reality they wanted. So everybody wins and loses.

THIS WEEKEND’S PERFORMANCE

The principal roles were all double-cast.

The leads (Mileeyae Kwon & JooYoung Bang as Hsing, Joseph Arko & Alexander Indelicato as Luis) were interchangeable. That is, their characterizations and vocal performances displayed no noticeable differences. They all sang well, and acquitted their parts as far as the music is concerned.

But the leads all struggled to deliver believable movement without the aid of props. Director Ricardo Herrera opined the limitations on properties available to the cast because of confined space in the wings, and a small stage crew. Quick set changes were necessitated by the musical score.

Two actors also performed the role of Hsing’s professor/husband (Canaval), and here the contrast was dramatic. I Sheng Huang’s characterization emphasized the character’s coldness and ostentation. Phillip Gay’s characterization emphasized Canaval’s warmth toward Hsing. They both got it right. As opera, it worked better for Huang whose sepulchral bass-baritone commanded attention. Gay sang tenderly by comparison.

The most vocally challenging role, fraught with melismatic exclamations and flourishes, was purposely thrust on the frothingmost believer among the Angels (Rosa, voiced by Yaritza Zayas & Anna Carr). Zayas had an easier time getting all the notes in, although I don’t know if that feat required her to take liberties with the timing. In any case, it’s a clever characterization: The gaudy presentation and musical bombast perfectly conveyed the archetypal religious nut.

Stephen Boyer (Bingdi) recalls Loki, or any mischievous character for whom you’d cast the best available insane actor (Christian Slater, Crispin Glover). Boyer’s eyes never quite focused on anybody or anything. Look for him in future villain roles. He’ll steal the show.

Outstanding performances came from contralto Bethany Stiles (Uma) and soprano Samantha Resser (Tirza), who best combined the two arts of singing and acting.

Stiles’s emotive facial expressiveness recalls Diana Rigg’s Avengers work. Like Rigg, Stiles job of conveying emotion was made easier because her face appeared on the big screen (via closed-circuit television, from an off-stage camera). Her two duets were gripping, among the best musical bits of the entire two hours. (The very best stuff was choral, usually voiced by the cult. It was delightfully creepy.)

Resser delivered a range of emotions, all believable. Her most dramatic moments (joy and terror) were directed at a doll, Tirza’s pretend infant human, and she nailed them.

THE MUSIC

Not minimalist, not an afterthought. The genius of Paradises is that the music doesn’t step on the toes of the singers; it directs their purpose. If there’s a reason to maintain opera as a genre for young composers, this is the reason.

That said, the free form (zero time, and odd-numbered time signatures) gave performers fits.

Consonance and dissonance made rare appearances, while mood held sway. For listening purposes, it’s original and inspired. For trying to hit your cues, it’s frustrating.

As Director Herrera said, the cast and crew would have been fine with a few performances under their belts. But in four total performances, each player voiced his/her major role twice. Thus, no one got off script. They all kept one eye on conductor Robert Rumbelow, throughout.

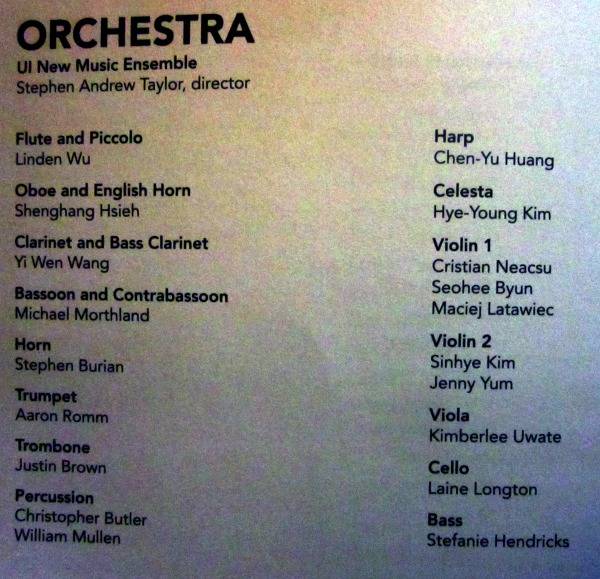

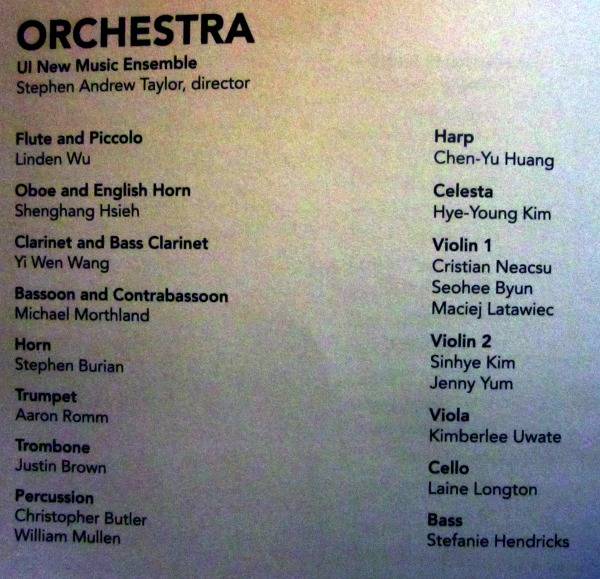

Rumbelow’s orchestra (which composer Taylor heads) featured a traditional string quartet, as well as the winds, chimes, bells etc. from Taylor’s original demo recordings.

Said Taylor “it’s based on the U of I New Music Ensemble, which I conduct. It’s a 16-player group, with one of each instrument, plus two violins and two percussionists. I added a few extra string players to create a little richer sound, and I also had electronics as part of the score.

“I’m actually pretty happy with the instrumental configuration. If anything, the electronics might blend too well with the instruments, so I might try to make them more artificial sounding.

“There are lots of timing issues. As we did more shows, the timing got better, especially for the ending, which at first was too abrupt. But Marcia and I are already talking about possible revisions; I’m starting to settle down on exactly what I’ll do, especially toward the end of the piece. Richard Powers and Bill Kinderman, amongst others, have given me some really thought-provoking comments and suggestions.”

Paradises Lost delivers its storyline in aria and recitative, but mostly aria. Orchestral music never threatens to drown the vocal delivery. Some duets (particularly the dual/duel baritones of cult leader Patel and romantic lead Luis) failed to achieve optimal vocal symbiosis because one singer could be heard better than the other. These are the little things you learn from a first production.

THE RESPONSE

With a marathon, an Ebertfest and Artists Against AIDS all vying for community participation, turnout was low on Friday night, and more than twice as big Saturday. In all, just over a thousand people viewed the first ever production of Paradises Lost. Different pockets of fans cheered for different performances from night to night.

But an effusive cheering came on Saturday, when Taylor poked his head through the cast. Almost everyone voiced his approval, in addition to clapping. It was as if the audience momentarily became its own retributive chorale. I was surprised by the outpouring, having seen the opera the previous night.

I guess the crowd sensed the significance, the epochal moment when the paradigm shifted: If opera survives, this will be its new direction.