A row of pine trees line the gravel lane that leads to musician Peter Adriel’s home, which is obscured as I approach on the county road. The driveway dead-ends at a pair of garages, next to which a trio of goats chew grass. As I step from my car, Peter approaches from his parent’s home and I get my first glance at the large pond that lies just down the slope.

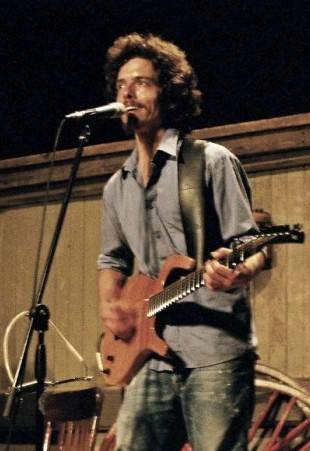

He’s a diminutive, shy fellow with a poof of wavy brown hair atop his head and whiskers above his lip. He shakes my hand and follows my eyes, which have darted toward what appears to be a solar-powered golf cart sitting in front of one of the garages.

“That’s a creation of my father’s,” Peter tells me, explaining that the panels atop the golf cart are indeed solar. The vehicle serves as a mobile energy source. If a fallen tree needs to be cut up for firewood, Peter can drive the cart to the tree and plug an electric chain saw into the cart, tapping into its renewable electricity.

Thus begins my visit to Peter Adriel’s rural home between Eureka and Goodfield, Illinois. His family’s 400-acre farm sits in the Mackinaw River Valley, where the land is gently rumpled. But Peter’s father, unlike so many of his neighbors, is not an organic farmer himself. Instead, Dave Kennell teaches courses at Illinois State University, where he heads up the school’s renewable energy major.

Peter suggests we begin my visit with a tour of the property. Context, as I’m soon to find out, is everything for Peter. This is where he lives and works. This is where he writes his music, a hybrid of country, folk, and rock. This is where he chose to return after years of living in distant locales, from Maine to Australia. We walk through a wooded area along a well-worn path cleared of thorny growth that leads to a hilly golden field. His uncle and cousin farm much of this land, Peter explains while my eyes remain glued to the ground in hopes of dodging cow pies. We come to a small ravine where a creek runs fifteen feet below.

“I built this fence to keep the cows out of the creek bed,” Peter tells me. Cows prefer to walk in the creek, which churns up the creek bed causing deep gullies to form. When it rains, soil and manure wash downstream in a muddy torrent. Fencing off the ravine encourages re-vegetation and decreases erosion.

The Mackinaw River Valley has some of the most fertile soil on the continent, and so the area surrounding Eureka is primarily farmland. A surprising number of organic farmers have taken residency here. Strolling through the pasture, the damp earth gives under the weight of each step, as if we’re walking on a small trampoline. It’s a gorgeous day — 65 degrees and sunny, the warmest day of the young year. Peter leads me to a large, lone hickory tree, its winter limbs contorting toward a cloudless sky. The ground is covered in shells that crackle under our boots. As Peter bends over to pick up the remnant of a hickory nut, he tells me how this is one of his favorite trees on his family’s land. He confesses that many of his songs are written in his head while he’s working and walking the land. It’s no surprise, then, to learn that Peter’s interest in ecology informs his music as well as his lifestyle. For the 29-year-old, his parents’ plot of land and generosity in sharing it with their son has allowed dreams to be fulfilled: Peter makes his meager living as a musician.

* * *

We settle for our interview on the stone and brick patio that extends from the basement-level walk out of his parents’ home. The view is distracting. Geese paddle across the surface of the large, man-made pond that serves as our foreground. Evergreens surround the pond and, coupled with the gentle slope of the land, help to create the sort of scenic locale not typically associated with Central Illinois.

As Peter begins talking, I force myself to concentrate on his words. When he was six, he received his first formal training, as did many other children, on the recorder. However, unlike many others, he was living in Paraguay at the time.

“There was a lot of music, big string bands with classical guitars and harps,” he explains of his memories of Paraguayan music. “I can vaguely remember the sound of the music, the sound of nylon strings.”

But the impact of another culture’s music had but a subconscious effect on Peter, as his family lived there when he was very young. He moved back to the States, to this particular patch of land, when he was seven.

“I grew up in the Mennonite church,” Peter tells me. “Singing is a huge part of what people do on Sundays. They do all this four-part harmony. But I never sang — not once — I just listened to it. Those are some of my first musical experiences — hearing the hymns. That’s where I got my first exposure to song form and chord structure, and verses and choruses.

“Simon & Garfunkel was my first major musical influence. We had The Sounds of Silence, and when I was in kindergarten I would play that thing over and over again. It has a song about Richard Cory, and I remember asking my mom what an orgy was, because Richard Cory would have orgies on his yacht.”

“Simon & Garfunkel was my first major musical influence. We had The Sounds of Silence, and when I was in kindergarten I would play that thing over and over again. It has a song about Richard Cory, and I remember asking my mom what an orgy was, because Richard Cory would have orgies on his yacht.”

Shortly thereafter, Peter would be introduced to a new lexicon of sexual terminology with the help of hard rock’s vernacular.

“In second grade, I went to Goodfield Grade School, and I remember that every kid in my class liked country music, except me,” Peter says as a few honking geese descend on the pond. “At that time I had a Van Halen tape and a Bon Jovi tape. So that’s what I got real into, hard rock. All the other kids listened to country music, and I hated it.”

As a young teenager, Peter met a common fate that befalls musically-inclined kids that age: The Beatles. His father purchased a CD player and began buying back the albums of his youth. Peter spent many months obsessing over these new sounds, in part because he had nothing better to do.

“The Beatles had a huge and profound impact on my life. When I was thirteen, I had Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. I was on chemotherapy for two-and-a-half, three years, and I was laying down for a lot of that time,” he recalls. “Some people gave me some money and I bought a CD player and I bought A Hard Day’s Night. For a long time, that was the only CD I had. From there, I went through The Beatles in a linear fashion, from there to Help! and Rubber Soul. The world just expanded. That music was huge to me. I spent years of my life listening to The Beatles while I was sick. Their music is healing, it’s full of love, it makes you feel good — that’s why the world loves The Beatles.”

While most children were wrapped up in teenybopper fantasies and pop culture, Peter was largely absent from such happenings — in his words, “behind the curve.” He bounced in and out of school while recovering from illness, and thus was often isolated. Left to his own devices and the influence of his immediate family, Peter began down a different path from his peers that led him to the College of the Atlantic, a school with fewer than 350 students tucked away in Bar Harbor, Maine, that offers one major — human ecology — and prides itself on its sustainability. In college, Peter’s musical ambitions began to crystallize under the tutelage of a certain professor. The young folkie began to blossom.

“My jazz music teacher had a derisive attitude toward folk music. Folk music is just strumming chords and singing words about stuff. And it’s dumb,” Peter says, in reference to his professor’s opinions. “You don’t necessarily know what you’re doing. You might know the chord is a G, but you don’t know why.

“I had learned theory. I had learned my fret boards in and out on the bass and guitar. I knew where all the notes were, and how to build chords and scales. And I was like, ‘screw that.’

“Neil Young was the reason I started playing guitar and writing music. Not The Beatles. The Beatles made me love music, but to this day there are very few Beatles songs that I’ve learned. Neil’s songs are really simple.”

The melancholic country-folk songs of Harvest. The heavier electric stuff on Live Rust and Weld. The mellower rocking material from On the Beach. All of it made an impression on Peter.

“There was a time for me when Neil could do no wrong. I would listen to a new Neil album and I’d hate it, but I would keep listening to it till I understood,” says Peter. “The sound he created on Harvest was such a magical thing that his record labels were always trying to get him to do that again, because it was so successful and people loved it. It’s luminous. … And I really like his words — I’m a lyricist first and foremost — and the visceral quality of his electric guitar playing. He brings something up from really deep. I love the vulnerability of his music. I’ve always been drawn to music that has obvious mistakes and weaknesses.”

Yet when it came to his own music, Peter had no such tolerance. He was writing a lot of original material, but he wasn’t a performing musician. He didn’t feel confident in his original material or in his aspirations to be a musician, and so he largely kept his music to himself.

“It’s a world of giants,” Peter says of the intimidation factor that burgeoning musicians often face. “The bar is so high. And in addition to all those people who are still out there, there’s all the dead ones. As long as we’re listening to music, we’re going to be listening to Johnny Cash, and The Beatles, and Elvis. … I knew as a writer that I had a long, long way to go.”

* * *

After two years in college, Peter dropped out and began travelling frequently to Oregon to spend time with a long-time girlfriend. When the relationship dissolved, Peter settled in Philadelphia, where he took a job at an olden shop that built and tuned church pipe organs.

“I worked with guys who were in the rock scene in Philadelphia, and I kind of watched what they were doing and talked to them,” Peter says. “It wasn’t until I moved to Oakland — ’cause my girlfriend was going to art school in Oakland — that I started going into San Francisco to open mics and I started performing. That was in 2004.”

Less than a year later, Peter’s relationship was on the rocks. A pair of his newfound musical friends were moving to Melbourne, Australia, and invited him along.

“The day that I got [to Melbourne] I went out and got a busking permit. From that moment, I started making my living playing music on the street, and that’s when I really became a musician,” he recalls.

In addition to his own songs, Peter performed old-time country and blues standards like “Pig in a Pen” and “Shady Grove,” which went over well with Aussie crowds.

In addition to his own songs, Peter performed old-time country and blues standards like “Pig in a Pen” and “Shady Grove,” which went over well with Aussie crowds.

“People were really grateful [for street musicians],” Peter says of Australian folks. “Besides that, they have two-dollar coins in Australia. If someone was feeling really generous they would just reach into their pocket and toss all their coins in your case. … I was paying $400-and-some for rent, and I paid that all in silver coins. It was all I could do to carry it in my backpack to the bank. Then I would use the gold coins to buy food and beverages. It was a great hand-to-mouth kind of existence.”

Peter returned to the States six months later, planting roots at his parents’ homestead with the hope of forming a band and maintaining a low overhead, so that touring could be a regular option. (He says his ideal would be to confine his possessions to whatever fits in a single suitcase, throw it in a car along with a pair of guitars, and hit the road to tour.) He quickly began refining his own songs, and later that year he self-recorded his first album, Illini Wind, a collection of live takes featuring an amplified acoustic guitar, a harmonica, and a foot drum constructed from a gasoline pump. For his second recorded effort in 2007, he recruited a full band, including occasional live partner Jake Van Horn on dobro and bass, and headed to a rural Southern Illinois studio to lay down tracks for Gates of Louisiana.

Peter’s baritone voice marries rustic charm with a strong sense of melody. His guitar playing is decidedly entrenched in the blues-country mold, and he occasionally flavors his music with eccentric touches like kazoo. Lyrically, he alternates between quirky narratives that recall the storytelling of modern folk pioneer Michael Hurley, and vivid confessionals that embody a deep-rooted interest in nature and the spells it can cast on idle types.

“For me there’s no line between nature and culture,” he says. “When I first started writing, I was most inspired to write about things outside of me. It was a long time before I wrote a love song; I wanted to avoid that whole territory.”

While Peter says he tries not to have a message about nature in his music, he hopes that his lyrics do remind people that it’s out there. He’s not the sort of person who needs to be forcibly removed from his environs and hauled off to a nature retreat. His home studio features a wall-to-ceiling window that overlooks his family’s pond. Even indoors, he is more out of doors than most.

“I have days where I spend the whole day on the internet,” he says, “but what makes me feel really good is being outside, doing stuff, eating food. … For Native Americans, their survival day to day was based upon the food that came out of the ground. That’s why nature meant what it did to them, and why it doesn’t to us. It’s possible to just ignore it now.”

Squawking geese chime in, on cue. Peter heads indoors and returns with his recent instrument of choice, an acoustic guitar that he modified last spring by placing a pair of kalimbas, or African thumb pianos, atop the guitar’s sound box. The idea was Peter’s own, although he says a friend recently sent him a link to a video of another musician who had the same idea. He lays the guitar flat on its back, on his lap, and plays the instrument as one would play a dobro. The kalimbas are custom-tuned to the guitar, and when played, they cause the guitar strings to also resonate. Coupled with foot percussion of his own creation (a license plate and various small pieces of felt adhered to a wooden frame), Peter has stumbled upon a rather unique sound.

Squawking geese chime in, on cue. Peter heads indoors and returns with his recent instrument of choice, an acoustic guitar that he modified last spring by placing a pair of kalimbas, or African thumb pianos, atop the guitar’s sound box. The idea was Peter’s own, although he says a friend recently sent him a link to a video of another musician who had the same idea. He lays the guitar flat on its back, on his lap, and plays the instrument as one would play a dobro. The kalimbas are custom-tuned to the guitar, and when played, they cause the guitar strings to also resonate. Coupled with foot percussion of his own creation (a license plate and various small pieces of felt adhered to a wooden frame), Peter has stumbled upon a rather unique sound.

“I was just trying to get both hands and both feet moving at the same time,” Peter explains. “You get the hemispheres of your brain talking to each other. Drummers are doing this all the time.”

He plays a song for me upon request, noting that playing acoustically — without voice or guitar amplification — is a rarity for him. He favors the transformation of quiet sounds into a loud setting. As he plays for me a newer song, “Julia Belle Swain,” his foot pounds the patio in rhythm. The family’s outdoor cat rests just inches away from his foot, not startled by the sudden movement or the sound. She lies there, peacefully taking it all in.

He plays a song for me upon request, noting that playing acoustically — without voice or guitar amplification — is a rarity for him. He favors the transformation of quiet sounds into a loud setting. As he plays for me a newer song, “Julia Belle Swain,” his foot pounds the patio in rhythm. The family’s outdoor cat rests just inches away from his foot, not startled by the sudden movement or the sound. She lies there, peacefully taking it all in.

Nature does appear to be in tune with Peter Adriel.

—

Peter Adriel performs with dobro player Jake Van Horn at Mike ‘n Molly’s tonight, Thursday, March 12. Christopher Bell, who SP profiled on Tuesday, opens, followed by Casados, who recently finished recording a new record, then Peter Adriel. Show starts at 9:30 p.m. and cover is $5.

Photography by Peter Adriel, except top photo by Shandon Connelly, live photo by Matt Erickson, and second photo by Doug Hoepker.