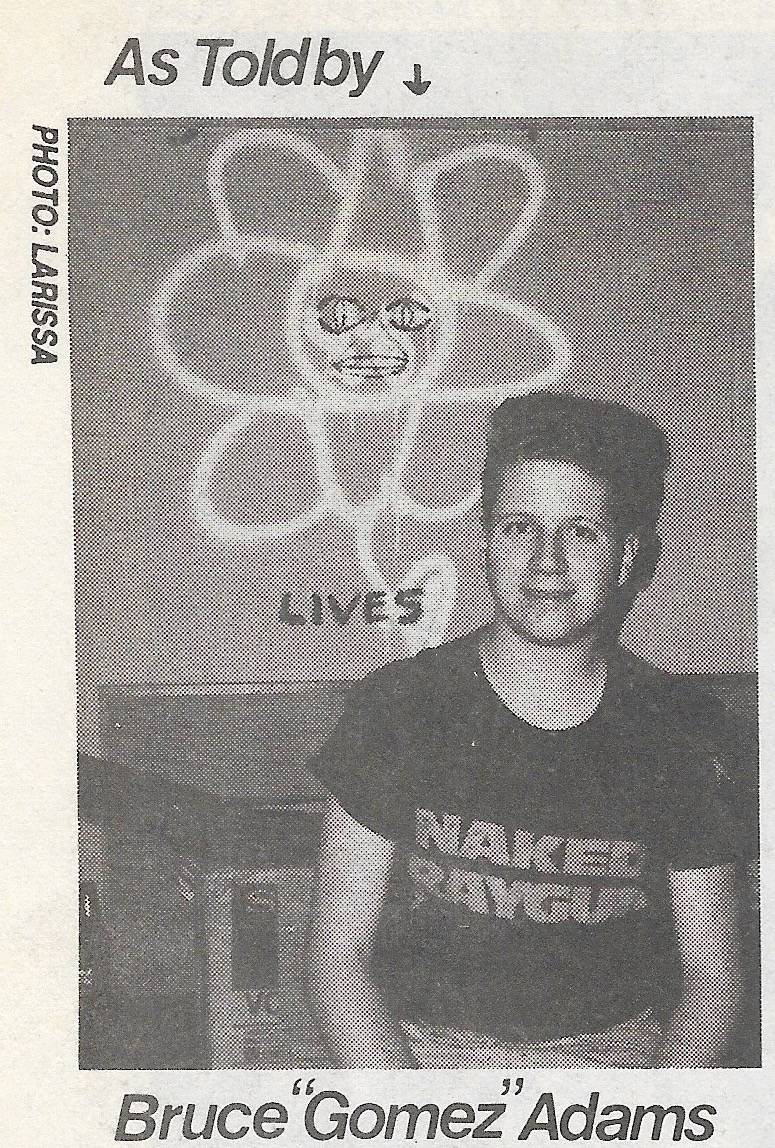

I met Bruce Adams for the first time in Urbana earlier this year, Flying Machine Coffee’s quaint patio on Main Street, Downtown. As many conversations go, especially initial, introductory, small-talk-based-ones — they end up spinning into basic questions about origins, past lives, and things of the like. I found out very quickly that Bruce Adams, Marketing Director at Common Ground Food Co-op, was the same Bruce Adams that co-founded Kranky Records in Chicago back in the early 1990s.

The same guy, living in Urbana now, working and living alongside his wife, Annie. The Adams’ moved to this community in 2014 and eventually bought a house here, realizing how cheap it is to live in Champaign-Urbana. You know, one of those perks that goes along with living in a community such as this. One of the first things he did when he got here? Picked up an Urbana Free Library card, and an ownership share to Common Ground. Come to find out later, these things would be far more representative of Adams as an individual, on top of his residency as an Urbana community member.

Though, I am realizing quickly that you are reading this in the Music section — so you’re most likely thinking, “what in the hell is Kranky Records?” You’ll see.

Adams has been down an interesting road — hailing form Syracuse, New York, attending the University of Michigan therefter, heading back to his hometown to get a Masters in Journalism, and then going back to Ann Arbor to begin what would be a super solid career in the music industry — managing a record store, to kick it off.

“This isn’t my first rodeo, it’s my fourth rodeo,” he mentions as we sit down to talk a few months after our initial meeting, over coffee, at the same clean-cut Urbana joint where we met a few months prior. We discussed a wide variety of things — Kranky, Champaign-Urbana, his time at the co-op, Pitchfork’s recent (and highly contentious) lists, and plenty of other topics. Adams began to tell me a bit about his background after he left Ann Arbor for Chicago, and how it connected to this place:

“I ended up becoming a roadie for the Laughing Hyenas. I came out to Chicago and ended up working for Touch & Go Records, it was shortly after the Didjits had signed to the label and their first record had come out. So I was here quite a few times to see shows and hang out, I had an early exposure to Champaign-Urbana — the music scene and all that. If you look hard enough in the “Captain Ahab” video, you can see me. [laughs]“

Going back to those “rodeos” — during Adams’ time back in Chicago in the early late 80s and early 90s, he spent time managing a record store (first rodeo), working for a record distributor (second rodeo), doing promo for Touch & Go Records (third rodeo), and then co-founding Kranky Records in November 1993 (fourth rodeo). While there were some other components in between those sessions, Adams described them as “pony trainings.”

As an aside to this entire discussion with Adams: Over the course of the last two or three decades, music and the consumption model has changed drastically. The early 1990s were such a distant and different time from this decade we’re currently in, as technology and culture has progressed. In regards to this particular component, Adams elaborates after I suggested that things have changed. From now, and how things were back then, decades back:

“It was an incredible time. We were still kind of flush in the phase of CDs, so a lot of people buying CDs, they were becoming economic to put out once the longbox was eliminated, and a lot of the packaging around CDs went away and you could just put things in jewel boxes. We just did a lot of things, and Kranky still does a lot of things with folders, cardboard folders. It became a lot easier to manufacture things, the cost per unit went down and so there was a great market on all sides.”

Though the indie rock scene in Chicago was one thing, Adams’ connection to this community runs a lot deeper than I had initially anticiapted, as I had asked him to do this interview based on Kranky’s reputation as an extraordinarily influential and meaningful record label in the grand scheme of indie rock. I asked about how things were back then because, hell, I was roughly a child until I discovered things much later in my existence as a human being in the mid-aughts:

“You might call it the ‘boom years’ of alternative and indie rock. I was working at a distributor called Cargo Records in Chicago — and Cargo has a sort of deep background with Champaign-Urbana anyway. I met Lisa Bralts-Kelly and Jim Kelly there. We distributed a lot of Parasol and sold directly to Parasol. Later on, John Isberg and the Firebird Band were on one of Cargo’s labels. So it was a time where there were multiple distributors across the country — the independent record store scene was probably at it’s prime and thriving.”

The connection here just had me floored to begin, which was all the way back in 1990-91 — where the highway between Champaign-Urbana and Chicago was traveled quite a bit more with bands going back and forth for shows, and a connecting route for tours to St. Louis.

“I saw Poster Children a lot in Chicago… I ended up seeing HUM and Steakdaddy Six and Lovecup — that whole group of bands — a lot on that route. There was a real pipeline going back and forth between the two cities. That doesn’t appear so obvious to me now, things have changed a bit. But in those days, there was a circuit that went all around the Central Midwest.”

This was just a single component which helped Adams move towards what he would end up doing for the better part of two decades — curating and managing what would end up being an extremely influential record label — after Adams’ partner, Joel Leoschke, and him had recieved what would become the beginning of their tenure as a label.

“One day he just waved me into his office and laid this 7” single we got from this band called Labradford — we had talked in a “barstool” sort-of-way about starting a record label. When we heard that single, we said ‘This is it. This is the kind of thing that you start a record label around.’ It was the sort of music we like, and it was so radically different than anything we were hearing, which were variations of the Pavement forumla. We really just thought it would be great. It turned out that when we got in touch with the band, they were amenable to working with us.”

Labradford.

To me, this is just as wild as it is calculated and predictable: band contacts distributor, distributor enjoys music, distributor continues discussion with said band. Wild, and as a sheer numbers game, slim odds that something comes of it.

To my former point — to imagine how many singles and demos Adams and Leoschke had received over there years is truly mindblowing, working for Cargo. For the ability to pinpoint and identify a band like Labradford as the beginning is remarkable. Following that, I asked how the discussions went once the duo was at least onto the idea:

“It went very well… we took a good deal of time, as we did with every band, to sort of explain what we had in mind and how we were going to operate business-wise, what people could expect from us, what we wanted to contribute, and things of the like. We established an understanding right from the get-go about what was going on. In the case of Labradford, they had to step off the ledge with us and they had to put their fate in the hands of two guys who were just starting something.”

Adams and Leoschke were doing something that provided a much different scope than what the average listeners was consuming in early 90s Chicago. While their aesthetic wasn’t initally well-defined, they knew they were interested in quality bands that were doing something that they thought had the potential to “go above and beyond one record” — and Labradford proved to be a prime example of that.

“I can think of very few bands that developed their sound from album to album to album incrementally and ended up somewhere pretty differently from where they started,” Adams said about the band. “Every record was measurably different from the one they did before, but still consistent with the band’s identity and their interest. We really came to the conclusion pretty early on that there were plenty of people doing what we would call ‘beer drinking rock and roll music’.”

They decided that isn’t who they were going to end up being, investing personal funds into what would become the label that would pioneer the experiemental and ambient genre in a lot of ways. As time passed, they ended up working with some absolutely spectacular bands — Stars of the Lid, Windy and Carl, Jessamine, The Bowery Electric, for starters. “Without patting ourselves on the back too much, I think we introduced a lot of what you might call ‘indie rock listeners’ to the more experiemental and abstract notions of music and fields of music that were out there”, Adams mentions. Without question, this label solidifies what it means in terms of true investment not just into a genre, but into a group of consumers and human beings listening to indie rock.

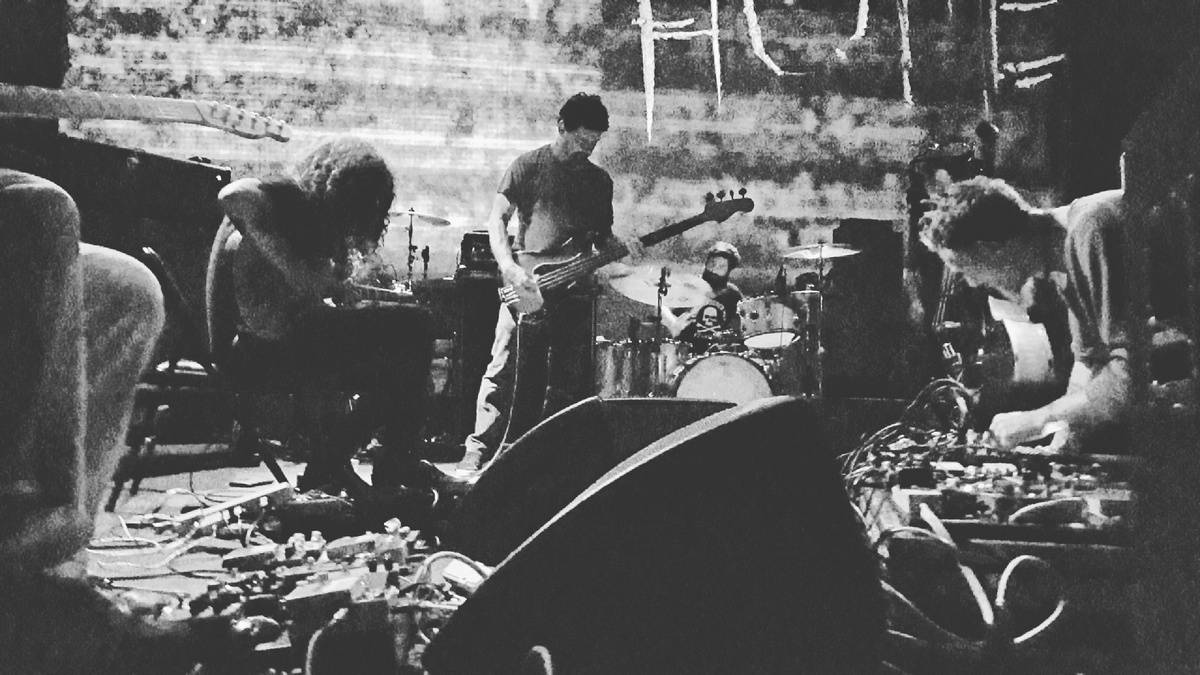

The link between Adams and the scene here runs deep, as mentioned previously, but our conversation ran even deeper — talking about one of the most influential bands, Godspeed You! Black Emperor. We talked about the idea that live music has become a bit more of a status symbol than it has been a point of experience.

“Well, it always was, you would laugh if I told you how many people told me they were in the room in the Lounge Ax seeing the first Godspeed You! Black Emperor show. You know, I know how many people were there, and I could count them on all of my fingers and toes. [laughs] That was in 1993, they opened for William Hooker.” Adams and his team went and saw GY!BE after they were contacted about the band coming through town, and “the next day, a couple of them went to busk underneath the “L” station, and we got breakfast.”

Whoa. This completely blew my mind. A band that had recently headlined Pitchfork Music Festival, and basically every other major festival worth a shit in the world, was once busking beneath a Chicago transit line? Jesus.

Godspeed You! Black Emperor.

Moving beyond what this GY!BE situation meant — seeing and experiencing music was brought into question, and in many ways (and in my estimation, as the author of this piece), is totally a status symbol. This is especially relevant in today’s day and age where digital exposure is everything. I am absolutely guilty of it, and will own it. In our discussion, Adams found that both good and not as much — “they might be giving me warm and fuzzy feelings, too — and that’s fine, and Lord knows my memory gets hazy” in regards to who he knows was there, and who mentions they were there. But, honestly — Adams has one of the best success stories to put on display, for instance:

“Number one, there’s nothing quite like the feeling of being in a room, or in my case, being in a field and seeing 20,000 people here to see a band you saw in a room with 25 people. So, that kind of blows your mind. A while back, Kranky had it’s 20th anniversary in Chicago. A bunch of shows, and it was great to be there and see all of those people in a variety of venues and various sizes — you feel good for the bands, more than myself. I feel good for the bands because their vision has been vindicated and their efforts recognized.”

While Godspeed had made it into the realm of legitimacy, it wasn’t always a certainty that they were going to manage this success — it was 1997-98 when Adams & Co. had found that their relationships with GY!BE and newly found relations, Low, were going to make this thing for real. When the time came and Low was performing at Schuba’s in Chicago, Adams remarked when Low performed in Chicago that year:

“There was a line out the door. So at that point, I was just like, “wow” — and Low is consistently on the road a lot, so we knew that they had a high profile when we signed them. So just the fact that we were able to do the number of records, and we knew that it would do well for us and we’d established a catalog — that is a big deal as a record label to have a back catalog so they were discovering our older bands.”

Of course, this acquisition of Low is a brilliant thing — but perhaps this is an indication of what Kranky truly meant not just to the Chicago scene, but indie rock generally. Adams and I started discussing these recent Pitchfork lists shortly thereafter — as the top 50 Ambient and Shoegaze records of all time had just come out. Adams, of course, had commentary.

“When the Pitchfork Ambient list came out, I was pissed off! [laughs] Labradford wasn’t in it, and I was pissed off. Windy and Carl had an album on it, Stars of the Lid had two albums on it, and a Grouper record as well — but that’s after my time at Kranky. What pissed me off about the Pitchfork list was that nobody, and this is gonna sound so arrogant, but nobody would be making lists of ambient music in the year 2016 if Labradford didn’t exist. I can say that, definitively. As one of a lot of people who read Pitchfork, I can unequivocally say that you would not be into this music if Labradford hadn’t injected it into the corpus of American indie rock.”

Holy shit. I actually follow and support this sentiment that Adams has. The more that I sat there and talked with him, the more that I understood his connection not only to indie rock and the industry, generally, but to this community and the artist(s) that had brought him up. His connection to this realm of culture runs only a few years deep, but the transition between Chicago and here find a ton of connectors. Through all four (plus) rodeos — these are great reasons to be alive and be involved. Lists aside, there’s a lot of humanity involved.

“I’m a connector, I always have gotten pleasure out of connecting people to things I thought were interesting and worthwhile,” Adams says. Perhaps that’s why he’s been involved with co-ops over the years, that being Cargo, Kranky, and now onto Common Ground (and his support of Urbana Free as well) — absorbing what’s going on here in Champaign-Urbana. Not only that, but his thoughts on art in C-U in just a few years existing here.

“I’d highly recommend the shows that are going on at Krannert Center. There are just an incredible wealth of things here, and then there are a lot of great musicians, and this is a real DIY town. People really go out and make their own fun.”

As far as I can tell — that’s the goddamn truth, not just Krannert component, but Adams being a connecting entity, and how Kranky altered the foundation of indie rock. While he’s not involved any longer, it is real. From rodeo one, to whichever the last rodeo may be.