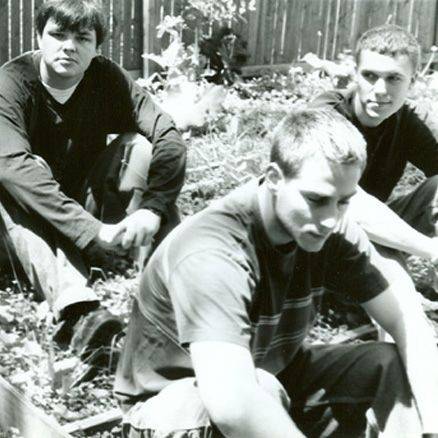

This Sunday, September 28th, American Football will perform in Champaign-Urbana for the first time in, oh, fourteen years or so, at The Pygmalion Festival. This is a beautiful intersection of interests — Mike Kinsella’s Owen project has performed at virtually every Pygmalion, but this will, of course, be his first time with his band which disbanded before the festival yet existed. It’s yet another wonderful inclusion of a Polyvinyl Records band on the lineup. It’s a return to songs written in and about college to be played in the town the band went to college in. And even though the group were only around for a handful of years, since their breakup they’ve come to be known as a major influence on musicians here locally, and globally as well. I had the pleasure of speaking with drummer Steve Lamos, and his responses to my perhaps goofy questions were very heartfelt and thoughtful.

Smile Politely: (How) do you consider the impact American Football’s limited-yet-dense discography has had on the musical landscape? Are you able to contextualize what you accomplished, or is it rooted in personal memories?

Steve Lamos: I really can’t contextualize it very well. For me, American Football was a really just a weekly practice session in my little house out in Urbana on Washington Street. Mostly in the afternoons. The fact that it’s apparently morphed into this other thing is still a little hard for me to believe. But, as a musician, I couldn’t be happier that folks care about the music after all these years. What a cool, cool thing.

SP: Are there any bands active now that strike you as having the spirit or energy that remind you of your time in American Football, or perhaps the bands and scene of the midwest near the turn of the millennium? What do you feel has changed?

Lamos: I’ve been talking a lot about the Dodos lately. I really like them, and I can’t help but think that they’re mining some of the same territory that we tried to mine back in the day. I like a lot of other bands, too, of course. By something about the Dodos really grabs me.

What’s changed? I’ve certainly changed: I’m 40 now, with two kids. And so music means something different to me now than it did in Champaign-Urbana. Back then, music was a huge part of life, maybe the biggest part for a little while. Now it’s more of a fun part-time respite from diapers and work and life.

SP: After enduring what I assume were fourteen years of people asking you guys to reunite… Why now?

Lamos: Why now? The first answer is Pygmalion: Seth [Fein, the festival producer] approached us through Mike [Kinsella’s] management, and he made it clear that he wanted us to play enough that he would help us to make it possible in terms of money and time and scheduling and all of that. This whole crazy thing starts with him, for which we’re very grateful.

Matt [Lunsford] and the Polyvinyl crew were a huge factor, too, of course: their willingness to reissue the record was a huge catalyst for playing again. We’re grateful to them as well.

Just as important, though, is the timing. Through some weird blip in the universe, we can all do this right now, even though we’ve all got jobs, lives, seven kids among the three of our families, and everything else. So, by whatever cosmic alignment, here we are.

SP: It’s strange and awesome to me that the house in Champaign-Urbana has become a sort of “emo pilgrimage” to fans. I do think that odd little window is a subtle metaphor for something quintessentially teenage. How much would you say the time period or geography affected the music that you made?

Lamos: Good question. I can’t say much about emo pilgrimages. And I actually still don’t know exactly where that damn house is: I’ve certainly never been in it (though I’m pretty sure that Mike has).

But I can say lots [sic] about C-U and what it meant to me, personally and musically.

I lived in Champaign-Urbana pretty much non-stop from 1992, when I transferred there as a sophomore to 2005, when I left for Boulder with my PhD. after a one-year stint at Illinois State University. That said, every single thing that I did musicially for 15 years was C-U-based. I idolized bands like HUM and Poster Children and C-Clamp. I played in bands that opened for Braid and Sarge and Angie Heaton and Castor and Absinthe Blind and Grover and a million other bands from that time. I hung out at the Blind Pig and the Iron Post and the Brass Rail and the Esquire all the time. Finally, toward the end of my time there, I got to know Ed Burch and play a bunch of different kinds of music with him.

All of those things were huge influences on my playing and my life.

That said, I’m not ever sure that American Football was really considered a “Champaign band,” at least not at the time. We probably only played 15 shows total, and I’m guessing that only three or four were in Champaign: there was a party or something with Rainer Maria, a gig at the Pig opening for Castor, I think, and one or two more.

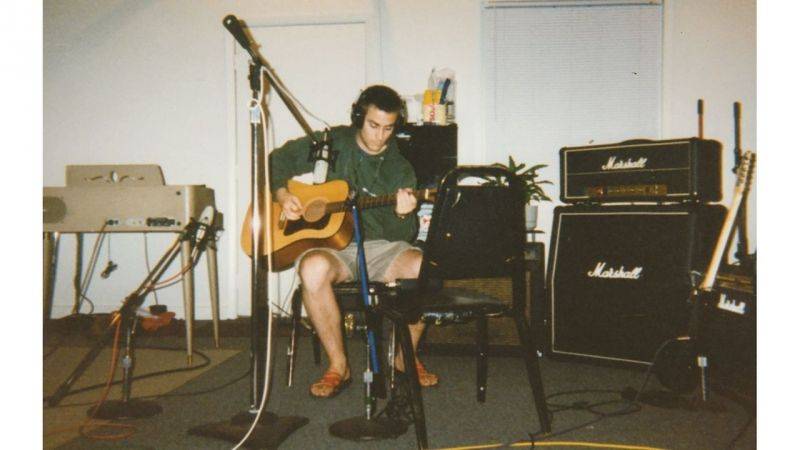

But we certainly wrote the music in Urbana, mostly in that little living room with daylight coming through the windows. (Mike and Steve also wrote their parts together in the couple of apartments that they shared over the years.) We definitely recorded in Urbana with Brendan Gamble in that small little Private Studios “B” Room. (I still remember, vividly, sitting down to record “Never Meant” in that room: the drum take that made it on to the album was the best I’d ever played that song.) And we were certainly happy to be an early part of the Polyvinyl lineup that has since become synonymous with C-U music. All of those things obviously meant — and obviously still mean — a great deal to me.

SP: What is it like playing these songs, that seem to draw from post-adolescent experience and emotion, now that you are all adults? Is it difficult to “get there”, or is that not really the approach or concern?

Lamos: You’d have to ask Mike the question in terms of how he feels lyrically. We’ve joked that these are “teenager” songs in other interviews, but I’m not sure that they really are, not even for him. Maybe they’re mostly about leaving known people and places for unknown ones.

Personally, though, these songs are rooted most directly in a space and time when playing music meant the world to me — a time when I was listening to everything and anything I could get my hands on while really learning to play the drums. Things were really exciting then: I’d hear something new that Holmes gave me, or some weird thing that my friend Ben Wilson from DMS would make me listen to, and I’d try to incorporate it into my playing. For me, that’s what it mean to “be” a musician, to keep trying to do different stuff.

Since 1999, there have been times when I’ve lost some, even most, of that exciting feeling with respect to music. Work, especially the working-toward-tenure part, beat the excitement out of me a bit. And having kids did, too, at least at first. This isn’t to say that I haven’t played out here in Denver or that I haven’t had a good time doing so. I have. But life here has been different with respect to music and what it has meant to me.

Until about 18 months ago, I started playing more frequently after tenure, and things started to click back in. Then this American Football stuff resurfaced: playing these songs again, especially in anticipation of some of the biggest gigs that I’ve ever played, has definitely stoked the fire for me in terms of wanting to play them as well as we possibly can — to “get there” for the people coming to see us.

For what it’s worth, I feel like we’re playing the music bigger and better and more forcefully than we ever did the first time around, especially with Nate Kinsella on the bass. There was always a big, heavy, space-rock vibe lurking in the American Football music, complementing the more introspective stuff. I’m hoping that we can make the live show reflect that. I think we can.

SP: The internet tells me that you write about writing. Unless that’s another Steve Lamos.

In retrospect, how would you qualify or describe the lyrical content of the EP and LP? Do you think the simplicity or straightforwardness of the lyrics is their strength? Or perhaps the longing tension within the music might imbue the words with further emotion? I understand that you’ve written about the teaching of writing, specifically. Do you see any influence in this current generation of lyricists?

Lamos: The internet tells the truth: I’m an Associate Professor of Rhetoric and Composition at the University of Colorado-Boulder. My book for tenure had to do with how issues of race and racism shaped writing instruction for students of color at U of I from the late-1960s through the early-1990s. My current book, still very much in its early stages, shifts gears a bit by trying to understand the value of space-based, place-based writing instruction in a neoliberal and highly technological age. Place and space and time are of increasing interest to me, then, as is affect.

Anyway, I say all of this so that I can better answer your question. I teach and write mostly about history and policy issues related to expository writing instruction. I don’t write about aesthetic issues. And so I’m not really the best person to ask about lyrical content or lyrical beauty or anything else.

I’ll even go so far as to say something potentially ridiculous for someone in my position: I almost never care about lyrics. I grew up listening mostly to jazz and the popular music from which jazz is derived. If lyrics appear in that sort music, it’s as a vehicle for melody, not as a vehicle for some profound self-expression. So when I first heard Dylan (which wasn’t until mid-college, I think), my honest-to-God first reaction was, “Does this guy ever shut up?” Obviously, I’ve come to love Dylan and his approach. But that type of approach is definitely not the one most obvious or comfortable for me.

Now to try answering your question. I really like and appreciate that Mike’s lyrics complement the music so well. Virtually all of the American Football songs were instrumental tunes first, with lyrics added at the end. As Holmes has mentioned in other interviews and in the new liner notes, Mike almost never sang at practice. We noodled with the songs, Mike wrote words and melodies on his own, and we essentially heard them with lyrics only during the relatively few times we played live and/or recorded. As I’ve gotten to know the songs again, I increasingly appreciate what Mike did lyrically to complement the music rather than run over it. He opted for simplicity and impact over the usual verse-chorus-verse-chorus stuff, and I think that it works really well.

SP: What significance does performing in Urbana-Champaign have to you, after all this time?

Lamos: It means the world to me. As I’ve said, I lived there nearly 15 years. I met my wife Tracy there. I made tons of music there. I essentially grew up there. To play there as our first official show in many years — really, our “record release” for the album and the re-issue all at once — is really amazing. I doubt anyone there that night will be as excited as I will be.

SP: Which are your favorite of these songs to play? Has there been any longing to actually play them since the band split? When you got back together to practice, was there a particular moment or song when everything “clicked” back?

Lamos: I like just about all of the songs, but there are a few that are especially fun right now because we’ve got Nate on the bass. “Honestly” is a blast, especially at the end, with some fat low end. And both “Five Silent Miles” and “Letters and Packages” have been transformed for the better by what Nate’s doing. But my personal favorite right now is the “7s” or whatever we’re calling that jam thing we used to do to close out our sets. That song is starting to reflect what the four of us can do together, and maybe hints at future possibilities. We shall see. But, of course, if people just wanna hear “Never Meant” like it is on the record, then we’ll give that to them, too.

American Football will be performing in Downtown Champaign for the Pygmalion Festival on Sunday, September 28th. They’ll be joined by the likes of Deafheaven, Maserati, Liturgy, and plenty of others. Grab your tickets here, or at the gate on Sunday evening.

FULL DISCLOSURE: Isaac Arms’ band Withershins is also performing during the outdoor shows on Sunday for the festival. Check out the whole schedule here.