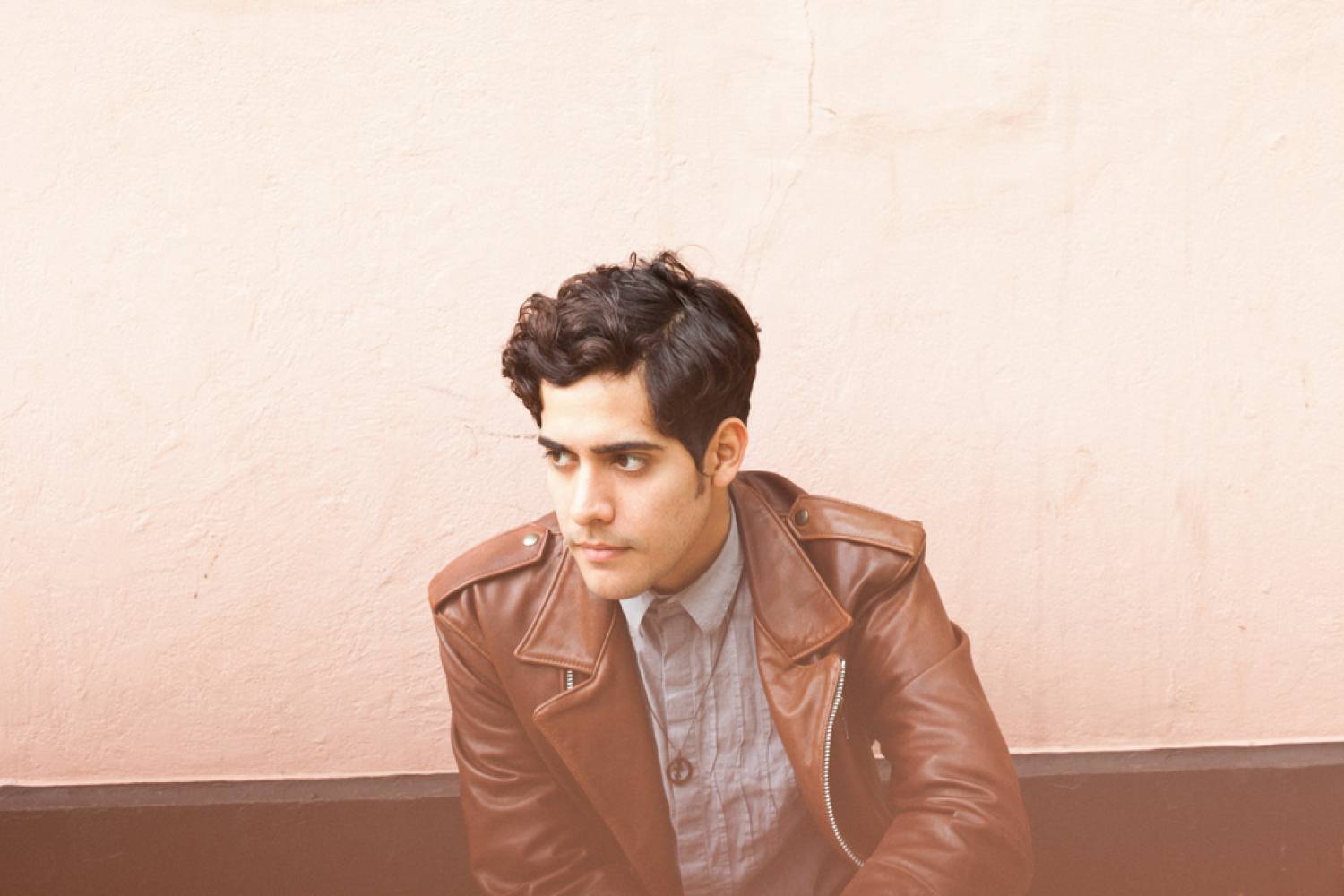

Neon Indian comes to Champaign this Sunday for the last stop on their US tour supporting the critically acclaimed album Vega Intl. Night School. Alan Palomo, the singer, songwriter, synth wizard, and producer behind Neon Indian has fashioned himself into something of a 21st century renaissance man. Studying to become a filmmaker, he dropped out when his side project as a self-taught musician took off. While working on his third album, he once lost the only in-progress copy of the files because he passed out drunk on a stoop in NYC with his laptop next to him. He gave an intriguing if slightly dense TED Talk about the myth of the autre in the artistic process. His boundless pursuit of his interests and unaffected attitude towards society has served him very well in his artistic pursuits, and makes for a very interesting conversation. I interviewed Alan last week and we talked about the arc of Neon Indian’s career, the role of genres in today’s music world, the construct of originality in art, his plans for the future, and much more.

SP: Night School took you four years to make, got rave reviews, and has a very ambitious and polished sound compared to your earlier albums. Have you written your masterpiece, or do you still have more you want to do?

Palomo: If Neon Indian were to continue it would require some aesthetic overhaul in order for it to remain interesting to me. It definitely felt like a trilogy. It felt like this last one in particular really satiated the things that I wanted to say when I initially set out to make this project, and one thing I don’t want to be is redundant. Writing records just to kinda feed the machine of what it means to have a band in 2016 is not something I have much of a vested interest in. After awhile it becomes less about a specific statement and more about just sort of maintaining “relevant content” to basically keep powering it. In that regard, I only want to make things that warrant their own existence, and that there’s a legitimate motivation to it and an impetus that spurs it. So as it stands right now, there are definitely concepts in mind, and my brother and I have been playing a lot of music together — if that will materialize into a Neon Indian record, I think it’s too soon to say. But it’s definitely hopeful and I definitely don’t feel like I’ve said everything I want to say in music, I just don’t want to be tethered to it in some way that it seems to benefit moreso the people that put it out and the machine that promotes it and perpetuates it rather than the artists itself.

SP: The title’s metaphor for learning from night life experiences sets the tone of the album. What did you learn from night school?

Palomo: First and foremost, you can’t write a song to make someone fall in love with you. That’s a pretty valuable lesson. This is a question that gets asked a lot in a very cheeky kind of way, but night school is presented as more of a metaphor of how a lot of people cut their teeth and create an identity and a social life. Where you move to a city for the first time, you might be out of college or out of high school, and you’re confronted with being social and being on your own for the first time. It’s always interesting to act as a spectator when I go out and I see these people that are trying to figure themselves out, and I thought it was just great fodder for this record. But it’s not like “a night school” or “what’s on the curriculum of night school?” the metaphor doesn’t go that far.

SP: This is the last show of your tour promoting Vega Intl. Night School — what’s next?

Palomo: Once we wrap things up in Champaign we’ve got just a few remaining dates in November (in Asia), but after that I’m kinda closing down the shop for a bit and rethinking what the next move is going to be. There are music-related things, but I don’t want to put the cart before the horse and try to describe a record I haven’t written yet. I think right now it’s just a moment to play into other mediums as well. As soon as I get back from tour I’m shooting a short film, and I just got done scoring a feature, so there’s been a bit more work in relation to that.

SP: I saw that you co-directed the amazing music video to your song “Slumlord Rising.” What was your involvement in that process?

Palomo: I was incredibly involved. My rationale behind it was — since the first record, I’ve had some really fantastic music videos and I’ve had the luck of working with some pretty great directors whose work I really admire, but it was always this process of setting aesthetic goal posts, in terms of what the video can and can’t be in terms of being in step with the aesthetics of Neon Indian. And so this time around I wanted to cut out the middleman and just start directing. Because I studied film in college, and it’s what I was heavily involved in until Neon Indian kind of just happened. So in that regard, there’s always been a bit of an itch to get to flex creatively in that medium as well. For me, it was a big growing experience because it was the biggest production that I’ve directed. Most of the stuff I’ve done has been commissioned shorts that have been more animated. This was a completely different process in terms of shooting in LA and the formalities of having a producer, securing a location, feeding everyone involved, and having like 60 or 70 extras.

SP: You’re from Denton, TX, a college town with a bit over 100,000 in population and a vibrant music scene (a lot like our own C-U), but you really broke through due to massive exposure from music blogs in 2009. Do you think your local scene was important to you, or could you have done it from anywhere?

Palomo: It definitely has a bit to do with being there because at the time the electronic music community in Texas was a little bit smaller, a little more limited. Because there weren’t that many of us, everybody knew each other and was communicating regardless of what city you were in. So we knew the other weirdo bands in Austin, Houston, Dallas, and Denton for that matter. Because of that, it created this environment of enthusiasm where everyone was excited to trade production tricks. It definitely felt like a slightly more communal thing.

SP: You were associated with the rise of Chillwave, one of the first genres to “form” online. In the past, genres were usually based around geography, and now it’s often music writers connecting dots. What is lost and what is gained?

Palomo: I don’t think there’s much to be gained anymore. I think it benefits the journalists more than it does the artists in that regard. The idea of categorization is getting so ridiculous, and the fact that we have ironic categorizations as they’re happening in real time, the fact that someone would spawn something like Simpsons-wave, whatever the fuck that’s supposed to be, I feel like we’ve gotten to this point where genre is parody, and to continue categorizing these things and pretending like there wasn’t a lineage of music that spawned those things is just kinda lazy. But I also think the term chillwave came when the era of blog-mediated music was at its height at that time. You know, it came from Hipster Runoff, and everyone had their different phrases, but that was the one that stuck because it was the most dismissive and sarcastic. But I’m kind of glad that the editorial MO on chillwave has died because I didn’t want to bear the brunt of having to carry some genre that I didn’t even identify with in the first place. So it was kind of nice to put out a record completely devoid of context and four years too late.

SP: Do you think there is a connection between you and other bands that have been called chillwave?

Palomo: Sure. At the most basic components, they’re lo-fi, they play synthesizers, it’s chillwave. But to play devil’s advocate, I can remember a time when if I would listen to a band and I was so excited by their sound and what they represented, then I would want to find ten other things that sound exactly like that so I could occupy my life with all this new stuff that sorta fits in the same ecosphere. But I think people get ahead of themselves, because you really want to let time do that. Genres used to be mediated by location, bound geographically, and dictated by a group of artists that knew each other, communicated with each other, and had common artistic goals, but now when someone just puruses a few Soundclouds and goes, “Yeah, I guess these are like similar in a way,” that’s where things draw mutation, and I would encourage the fans to work a little harder to create their own perception of what that might mean. Like, what are the similarities, but also what are the dissimilarities, and where is their sound coming from? Because obviously some of us are going to have different influences. To say I sounded like Washed Out or Toro Y Moi or Ducktails — sure, in the sense that we like the sound of tape and we like drum machines and synthesizers, but if those are the basic raw ingredients, then is Bruce Haack chillwave because he put out lo-fi electronic music in the 60s?

SP: Your music combines pop and electronic music with psychedelic influences. Do you have particular inspiration for your psychedelic art?

Palomo: Psychedelic is a pretty broad term, especially now that it’s fifty years since the 60s. It’s funny because I’ll play something and show it to a friend and be like, “Is this too ‘pop?’” and they’ll be like, “What are you talking about? This is completely fucked-up sounding”, but I just gravitate to sounds that feel somewhat tactile or textural. Especially with the first record, writing three-minute Beatles-y type structured songs, where it’s like, “Cool, now we’re going to the pre-chorus, and now the pay off with the chorus…” So in that sense, I feel that structurally it never felt like anything other than pop music. But the psychedelic elements were all about context and memory, using memory like an instrument, and evoking places that feel very visual and feel like they can house some kind of narrative, whether it be a movie or something more personal to your life. The way you listen to an old Aphex Twin Selected Ambient Works and you can imagine the space it’s playing in just by the nature of how it reverberates. And I was always fascinated with that, but doing it on my own shoe-string budget sort of way.

SP: In your TED talk, you discussed the myth of the auteur and how no art is original – it is all drawn from inspiration from things that came before, and yet we place a high value on originality. Why do you think that some things get labeled as derivative and others get called original, and do you judge your own writing process on those terms?

Neon Indian performs at The City Center on Sunday, October 30th at 8 p.m. Tickets are $21 in advance/$24 at the door.