Chillwave has gotten its fair share of negative press. As a musical genre (and I’m applying the term loosely) it does not command much attention from the listener. Often the lush songs drift too far into the dreamscape territory to where they simply sound like the pandering of some bored teenager experimenting with midi-controller keyboard and new recording software.

Chillwave has gotten its fair share of negative press. As a musical genre (and I’m applying the term loosely) it does not command much attention from the listener. Often the lush songs drift too far into the dreamscape territory to where they simply sound like the pandering of some bored teenager experimenting with midi-controller keyboard and new recording software.

The New York Times lambasted chillwave (a.k.a. Glo-fi) as “annoyingly noncommittal,” referred to the singers’ voices as “diffident” and too drenched in reverb too matter anyway. No part of the critique stung as hard as when the genre/movement was called “a hedged, hipster imitation of the pop they’re not brash enough to make,” but quickly rebutted the argument by admitting one of the bands they cited might be able to produce a hit (though it was phrased as if the bands would have to fall ass backwards on such a success).

I myself have been pretty squarely in the camp of the NYT so far regarding chillwave. Nothing I have heard from the loose assembly of artists moving the genre forward has left a memorable impression. However, it is a genre that I cannot ignore; evidenced by the few, but important, chillwave bands who have made their way to prominent spots on the Pygmalion lineup this year.

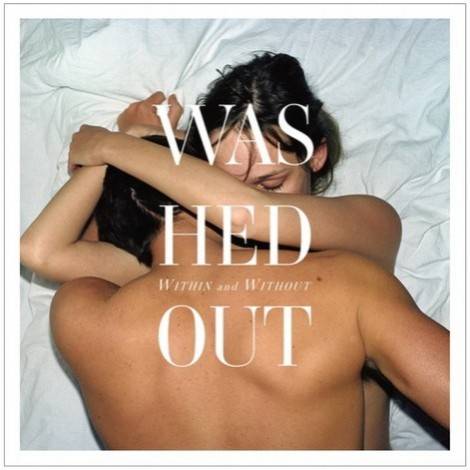

One of those bands, Washed Out, released its first full-length album on Tuesday, July 12. For the sake of ensuring I have the best Pygmalion experience possible, I knew I had to give the album a chance.

Washed Out began as the bedroom project of producer Ernest Greene. In 2009 and 2010 he created a pair of EPs as Washed Out that earned him great praise on the Internet for his sultry concoctions of ’80s soft rock and beats recalling Cut Copy. This buzz earned him a deal with Sub Pop that became Within & Without, his debut album.

The best part of W&W is the production. With the backing of Sub Pop came the ability to move Washed Out from his bedroom to a real studio; with that liberation Greene is able to create a fully formed album that does not have the hollow feel NYT criticized the genre so harshly for.

Where computer generated instruments and hollow beats may have filled the music before, Greene is now able to offer live drumming and instrumentation. This makes the synthesizers, which still dominate, feel much more engrossing than the chillwave music I have heard previously.

W&W never comes close to being brash, as NYT might have wanted, but on its most poppy track, “Amor Fati,” the hooks are much more developed and focused. The whole album has more focus than most chillwave music, and has continued to earn Greene critical acclaim — including from Spin, who called it “chillwave for people who can’t stand chillwave.”

For me however, it only makes chillwave more tolerable, not necessarily something I truly enjoy. The synthesizers drift beyond lush and on past dreamy into territory where they simply sound excessively reverbed. The vocal style of Greene, and more broadly the whole genre, was rightfully criticized by NYT; the words simply fall to the background, mingling with the synths somewhere in the echoey wasteland.

If you’re a big chillwave fan, as some readers are bound to be, then I believe this is an album for you. For me, though, it still doesn’t work. I guess I’ll be at Café Paradiso for Jessica Lea Mayfield instead of catching Greene at the Canopy Club come September.