When university students here in Champaign-Urbana or elsewhere are deciding on a major as an undergrad, many are faced with a big question: “How can I use this in the future?” Many Fine Arts majors are questioning their ability to thrive in this economy, and for good reason. Arts programs are typically cut first, and departments of the arts are routinely underfunded in America. In the ballet business, contracts are often negotiated yearly, and something similar also happens for orchestra players. It can be a rough lifestyle. And yet, there are still very successful and talented artists out there, making a living doing what they enjoy.

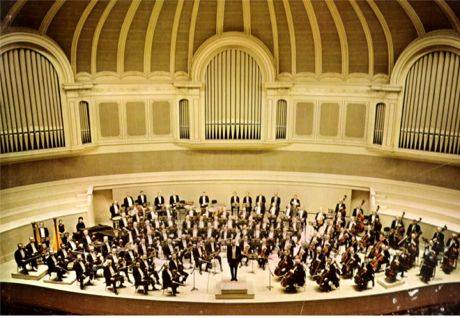

Florence Schwartz-Lee has been a violinist for the reputable Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO) since 1989. I recently had the opportunity to engage her in an interview concerning the recent CSO contract negotiations. Ms. Schwartz-Lee spoke to me about life as a CSO performer, the strike, contracts and negotiations, as well as about what the upcoming generation of musicians might need to expect.

*****

Smile Politely: Earlier this year, in September, there were contract negotiations for the CSO. Are contract negotiations a typical thing to deal with as a musician for the CSO?

Florence Schwartz-Lee: This one is for three years. They’re for three and five years depending on the time. I think the last one was for five years.

SP: Why do you have to negotiate contracts?

SP: Why do you have to negotiate contracts?

Schwartz-Lee: The contract deals with both salaries and benefits, as well as working conditions. For instance, how many services we have per week … [For] example, a typical work week is eight services, involving rehearsals and concerts. They have to pay us extra for other services or concerts. Change in the economy is why we have to negotiate; otherwise, we’d have the same salary for 100 years. There’s a national trend in healthcare. Up until very recently, our healthcare was essentially free; now, it’s not free. In fact, that was one of the main sticking points. We pay, we contribute a certain amount toward our own healthcare, and that’s because of how things have been going nationally. The orchestra doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It’s affected by the national economy.

SP: So, how were you all depicted in the media during the strike?

Schwartz-Lee: How it’s depicted in the media is that we’re greedy. And we don’t like going on strike, because we like to perform. We don’t like to disappoint the audience and withhold concerts. Nobody likes a strike. It’s a last resort. And actually, we played without a contract for a couple of weeks, I think. That’s what we call playing and talking, because usually, we won’t play when we don’t have a contract, but this time, we did.

*****

In articles such as the Chicago Tribune’s staff report on A&E, it was reported that, “Rutter (President of the CSOA) said the current average annual salary of CSO musicians, who have a base salary of $145,000, is $173,000.” This average, however, from a statistician’s perspective, neglects to inform readers that the average is skewed, since principal players are paid more than section players, such as Schwartz-Lee. It also conflicts with reports other newspapers have published. In The Huffington Post’s article on the strike, Katherine Brooks wrote that, “They (CSO musicians) rejected a three-year contract offered by the association that would have provided them with a weekly base salary of $2,795 in the first year, $2,835 in the second and $2,910 in the third, according to a statement released by the CSO. The previous contract afforded them a weekly base minimum salary of $2,785.”

The annual salary as calculated by the first year’s projected weekly base came out to be roughly $134,000. This base salary, however, is also based on averages. Not only do section players make less annually, but also, they have children to support, life expenses to consider, mortgages to pay, and college educations for their children to pay for as well. After discussing media backlash and contract negotiations, I questioned Schwartz-Lee about how it all played out, and how it is to have to go on strike in the first place.

*****

SP: So, how does it feel, to you, to go on strike?

Schwartz-Lee: It’s horrible. It’s not something we choose.

SP: How exactly is it organized? How do you all decide to go on strike?

Schwartz-Lee: We have a negotiating committee, and we vote to give our committee the authority to call a strike. It’s sort of an ongoing process… If things are going badly, we have a special meeting in which we get very little information, but they tell us, “Things are not going well; can we call a vote to authorize a strike?” We are unified. We are told to follow the recommendations of the committee, so that we present a united front. I don’t like being given not enough information. Some want to know the details of the issues, but we aren’t told those things, because they don’t want it in the press. We assume that it’s all in our best interest. There’s a hotline for how they inform us. It used to be by phone, but now it’s by email usually. For a strike at the last minute, they call. I found out there was a strike as I was on the way to work. My last name begins with an S, so I hadn’t received notification yet. It should have been done several hours in advance, because people who were on their way to the concert as well were affected.

Schwartz-Lee: We have a negotiating committee, and we vote to give our committee the authority to call a strike. It’s sort of an ongoing process… If things are going badly, we have a special meeting in which we get very little information, but they tell us, “Things are not going well; can we call a vote to authorize a strike?” We are unified. We are told to follow the recommendations of the committee, so that we present a united front. I don’t like being given not enough information. Some want to know the details of the issues, but we aren’t told those things, because they don’t want it in the press. We assume that it’s all in our best interest. There’s a hotline for how they inform us. It used to be by phone, but now it’s by email usually. For a strike at the last minute, they call. I found out there was a strike as I was on the way to work. My last name begins with an S, so I hadn’t received notification yet. It should have been done several hours in advance, because people who were on their way to the concert as well were affected.

*****

Patrons who bought tickets for that Saturday night were equally dismayed, since CSO performers went on strike an hour and a half before the performance was to take place. Strikes in general are out of the ordinary for the CSO, and it is certainly not a normal occurrence for CSO musicians to go on strike before a concert. The strike, which began the night of September 22, 2012, was only for a short duration, but its initiation has been called into question.

*****

Schwartz-Lee: It was actually not on purpose. That is not what we want to do to our audience. And if we were going to be on strike, I’d prefer to know sooner, rather than while I’m on my way to work. It was not a good idea for everyone, but we got a slightly better contract, and it only lasted two days.

Regardless of the stress of this situation, contracts were agreed upon, and Schwartz-Lee seemed very positive about the CSO’s future. Engaging further, I asked her about her experiences as a musician, and also, about what younger players might need to prepare for due to the current economic crisis.

SP: Would you say that working for the CSO is fulfilling?

Schwartz-Lee: Yes. It’s fantastic. I am, I think, in the best orchestra in the world. It depends who you ask. Some might like Vienna better, but we’re right up there… I couldn’t ask for anything better, for me, as a mother.

SP: Where have you traveled? What places have been your favorites?

Schwartz-Lee: I’ve traveled all over Europe, South America, and we just went to Mexico for the first time. We’ve been to China, Japan, and Hong Kong, and this trip coming up, we’re going to Taipei and Seoul, and those are both firsts.

SP: Where’s your favorite place to go?

Schwartz-Lee: I like London. It’s not as exotic as other places, but it helps that I can understand the language, and the people are so friendly.

SP: What advice might you have for musicians trying to break into the music business?

Schwartz-Lee: Practice until you’re blue in the face.

SP: Even if you don’t play trumpet?

Schwartz-Lee: Yes.

SP: Do you think, in this economy, that playing in an orchestra, or trying to play classical music at all is something people can pursue as a profession? What might the next generation of classical musicians need to prepare for?

Schwartz-Lee: It’s getting more difficult. A lot of orchestras are folding. Minnesota Orchestra has been locked out. Atlanta Symphony took a huge pay cut. Definitely, music is having a hard time. But, if you go into music, it’s because you have to — you have a passion. It’s not about making money. If you want money, then you do something else.

*****

Florence Schwartz-Lee has two sons in college: Solomon and Max. She resides in Winnetka, Illinois, with her husband William Harris Lee, her daughter Sally, and two lovely hypoallergenic dogs named Ruby and Baci.