The 2020 election brought scrutiny of the voting and ballot counting process to absurd highs, when the prolonged process of counting mail in ballots caused enraged Trump supporters to show up and bang on voting center doors in several states, demanding that they stop counting ballots, after months of being primed by the former President to believe that there would be voter fraud. With the “Big Lie”, that Joe Biden did not legitimately win the election, repeated over and over by right wing pundits and politicians ever since — even by the Republican County Clerk candidate in Champaign County — there will surely be plenty of people ready to declare fraud should key races in the midterm election not go their way.

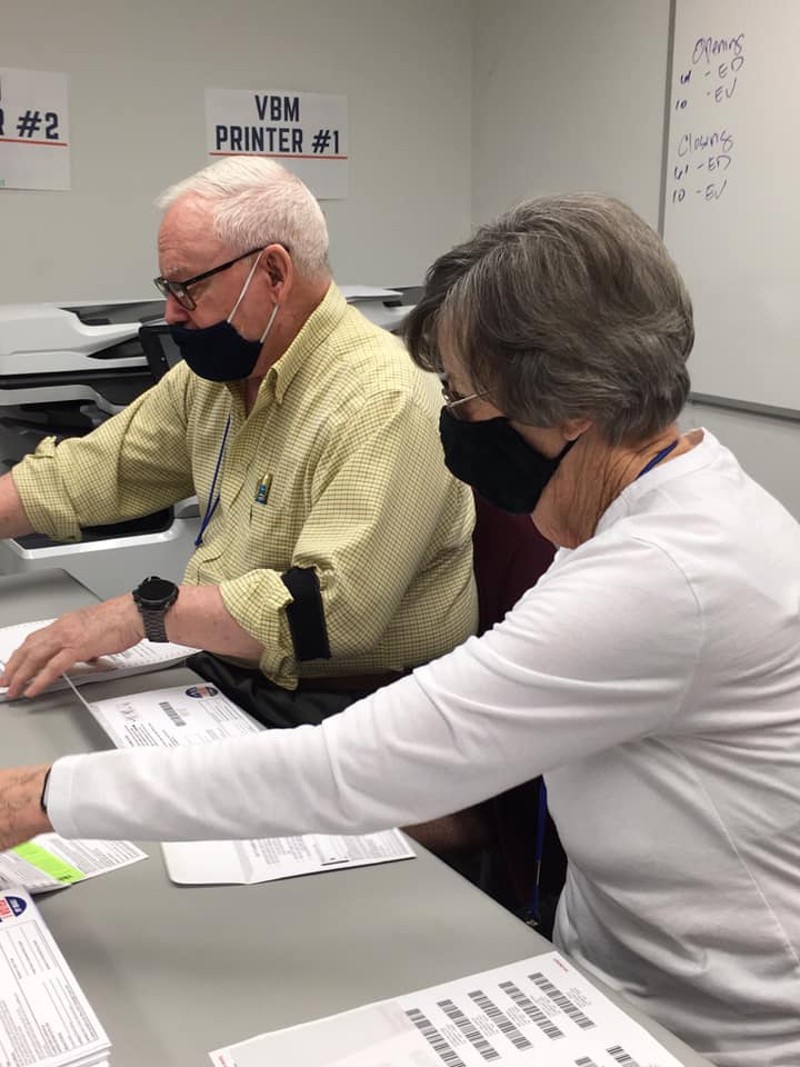

At the center of all elections are election workers, community members that sign up, go through training, and assist in every step of the process — from handing you your ballot, to counting and filing mail in ballots, to picking up ballots from drop boxes. They preside over the strict, highly regulated system of making sure that ballots are valid and that your votes are counted in a controlled and ethical manner. Here in Champaign County, these workers are referred to as election judges, and there can be anywhere from 200 to 600 people that will serve in this role during an election cycle. It’s modestly paid work. Judges in Champaign County are paid $13 an hour.

I had the pleasure of speaking with two of Champaign County’s dedicated election judges, David (Dutch) and Barbara (Barb) Powell. They’ve lived in C-U for over 40 years. Says Dutch, “We came here for three years with the Navy ROTC and forgot to leave.” They both have a masters degree in Educational Psychology. Barb went on to get her doctorate and taught at Eastern. Dutch served in the Navy until 1987, then went on to teach at the University of Illinois. They are both retired, have been election judges in Champaign County for more than 10 years, and have worked under three different county clerks: Mark Sheldon, Gordy Hulten, and now Aaron Ammons.

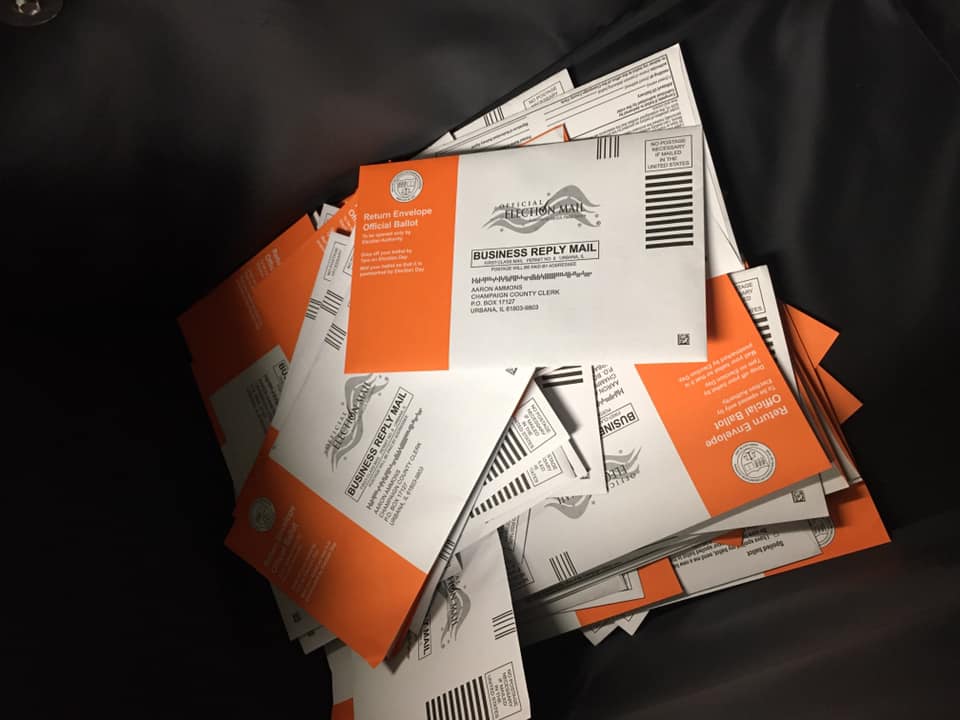

Photo from Champaign County Clerk and Recorder Facebook page.

Their roles have changed throughout the years, as voting access has expanded in Champaign County. They began as election day judges, because that’s all that was available. Once early voting was added, they assisted with that, and beginning with the primary of 2020, as mail in voting became available to everyone, they began working in the clerk’s office processing those ballots.

“The training was significant,” says Dutch. When they began serving, it was in-person. It’s now shifted online and takes about six hours to complete.

I asked what the most challenging part of their work is. According to Dutch, it can be poll watchers. “Every once in a while a poll watcher will overstep his or her bounds. When that happens, as judges, all together, we can decide to revoke poll watcher privileges. It doesn’t happen very often, but it’s happened within the last couple of weeks.”

In processing mail in ballots, Dutch and Barb and their fellow judges are doing signature verification. “There was a guy in the office who was watching the signature verification. He was supposed to be on a stool, behind some tape, and he was over the tape standing right over the two [judges].”

Dutch says that’s really the crux of the recent uproar about fraud. “How do we know this person is this person?” They’ve felt the heightened partisanship and distrust about the process, even from friends. “We have a friend who’s convinced it’s all a scam,” said Barb.

She goes on to describe what happens when your mail in ballot first arrives at the clerk’s office. “The ballots come in, and they get checked and stamped. Then they get signature verified. After that they get opened. There’s a machine that opens them. You make sure that you have the number of envelopes as you have ballots.”

Dutch interjects, bringing up an instance during a recent primary where the numbers were one off. “We spent weeks trying to figure it out.” They determined the error came from a particular precinct, and began calling voters to figure out what happened. “This speaks to the level of professionalism in the office.”

As for signature verification, Barb says that probably 95 percent of the signatures are exact or close enough, less than five percent are questionable, and maybe one percent of those don’t seem to match at all. Those voters will get a letter letting them know their signature doesn’t match, a letter that Barb writes and sends.

The Powells, who are registered Republicans, are baffled by the claims of widespread election fraud. They see the day to day minutiae of ballot processing. Dutch emphasizes that fraud does exist, but it’s often not for malicious reasons. Maybe the husband signs his wife’s name, or a nursing home worker signs for a resident that cannot sign for themselves. That’s fraud, and it can happen. However, they know just how difficult it would be to pull off the scale of fraud needed to sway an election.

Dutch talks about the process of collecting ballots on election night. “We get both the hard copy ballots, and tabulated ballots from each tabulator on thumb drives. We are there until the last tabulator comes in…Every one of those thumb drives is removed in the presence of a Democrat and a Republican. It’s brought to a room where I sit, along with a Democrat. He or she will put them all online. I’ll watch as they load it. I take it and put it in a pink pouch, and that pouch is sealed. It never leaves my sight.”

Because Democrats and Republicans are working side by side throughout the election, Barb says that it diminishes some of the demonizing of each side. “Everybody we’ve worked with has been great. When you get in there, and actually work with people, you start seeing them as human beings.”

She says that she feels like they are really contributing something by doing this work. “It’s a chance to do something worthwhile.” The Powells also like knowing how elections are run, and would like to see more people sign up to be judges, if only for that reason. “We’re not sitting around plotting.”