I’ve been restless all summer.

Yes, I’ve been consumed with my child’s vigorous and varied summer camps rotation, her grandmother’s senior activity gauntlet, and that endless list of summer projects (i.e. piles and stacks and mountains of domestic combat to wage).

However, in the midst of all that, I have also been managing a stronger emotional current. While running the family carpool, I’d catch a snippet of some discussion of “criminal and rat-infested” locales describing places I loved or have loved ones. Or I’d be putting dinner on and see babies lying on floors in mylar blankets.

My quick remedy to steady my nerves and resist our national “sunken place” was sending cards to migrant families, or sitting in on a legal activist webinar to get the latest info from the border, or catching Reverend Barber doing something somewhere.

However, I hit a summer low when our seven year old daughter came to us one morning and asked “if we would have to go back where we came from,” and when, in her bedtime prayers, my baby started praying “God PLEEEEEEASE make America great again so nothing bad will happen.”

Thus, my husband and I had to sit her down and have the other talk. We sat with her and talked to her about her own citizenship, her parents’ citizenship, her grandparents’ citizenship — a citizenship that dates back to at least 1867 on her father’s side (based on the earliest records kept on his enslaved ancestors). By the way, exactly how many talks do black parents have to have in America?

Sunday mornings, I would go to church expecting some guidance, some solace, maybe a prayer for those grappling with the same kinds of issues, questions, heartbreak I was managing regarding American race relations.

Consequently, during this moment of heightened racial tension in the country, I reached out to local faith leaders about concerns being raised in the community and what they are preaching and teaching during this time, and the “When Faith Speaks” series was born.

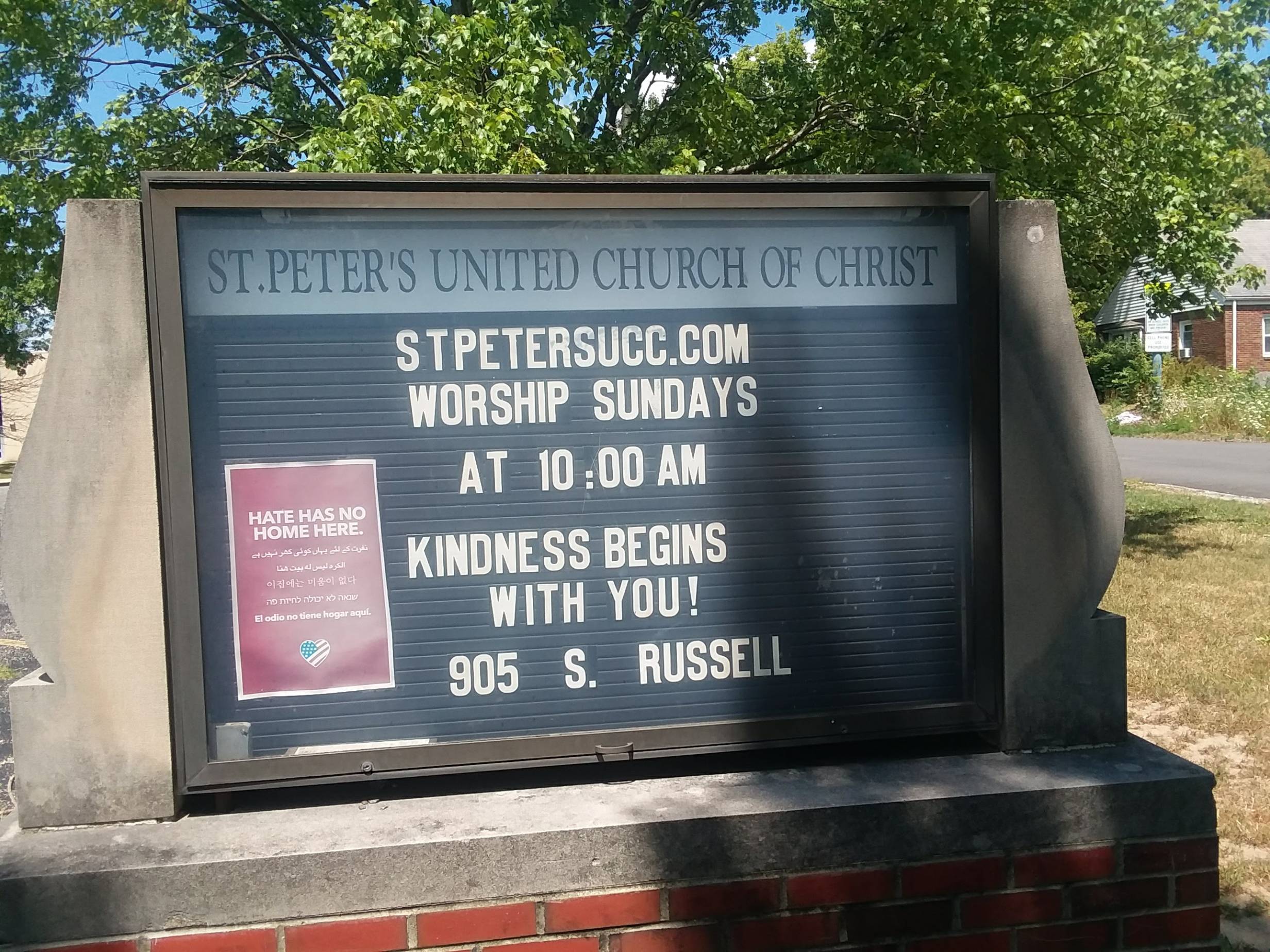

I visited St. Peter’s United Church of Christ for the first time during a 2018 Good Friday service and was reminded of all the architectural and spiritual gems hidden in plain sight across Champaign-Urbana. The sweetness of the ushers and the grandeur of the place always lingered whenever I thought about this church.

I spoke with Reverend Deborah Owen, senior pastor of what she describes as a “small congregation/big building community.” We settled into her office and we dove right into an expansive 75-minute discussion of issues of the day, beginning with the recent shootings in El Paso and Dayton and Brooklyn.

Reverend Owen: I was on Facebook recently, and someone asked if there were churches saying anything about the shootings. This person was disappointed that nothing had been said directly where she worships.

And so my response was that “Yes, we said something.” But tragically, this has been an ongoing thing. Every week, it seems we are saying something about a shooting or some act of violence that his happening nationally or locally. So one wonders when we will have a time period when this ISN’T happening…we don’t go from one week to another hearing about this.

There were these tragic losses of life in Dayton and El Paso, but there were two shootings in Brooklyn within 10 days. I have family members in Brooklyn. There may not have been as many killed or injured, but those people were harmed profoundly by someone with a gun.

In my prayer time about these matters, I said:

“Lord, I don’t even know what I would say to you as a fellow American is about to shoot me.”

One of our parishioners came to me and said it had never occurred to them to think about it in those terms, that this is one American citizen shooting another American citizen. For that one person listening to me, it was an “ah-ha moment”, a reminder to me that it takes those kinds of words sometimes to penetrate the normalcy of these events and actually reach someone.

In the meantime, we as a congregation, we are also looking at how we can be a safe place, not just in the face of violence, but also as a tornado shelter as well for our neighbors and the school next door.

I am just committed to having a non-violent response to violence.

Smile Politely: Do you think that your position of wanting to have a peaceful, non-violent response comes from the position of the United Church of Christ? Does your national denominational philosophy inform your thinking on this issue?

Owen: Denominationally, we are not “peace church” like the Quakers, but we do advance a more peaceful way of addressing things. We are congregationally-based, so the national church doesn’t dictate how we think or what we say locally. Nonetheless, like other mainline churches, our national body encourages local congregations to speak where Jesus wants us to speak out to address social issues.

SP: How do you negotiate notions of separation of church and state during these moments of heightened national tension? Do you feel pressure not to speak out?

Owen: No, don’t feel pressure not to speak! If anything, I feel personally that Christ is calling me to speak out and I thankfully have a support system. However, even if I didn’t not have a support system, I would still feel obligated to speak out because as ministers we are going to be compelled by compassion to say or do something.

In Dr. Martin Luther King’s discussion of The Good Samaritan, we ministers are called to do more than talk about the characters on the road. We are also called to accompany folks along dangerous roads. However, we also have to question what makes the conditions on the road itself so violent.

SP: So, are you currently in a preaching series? What are you preaching to your congregation right now?

Owen: Yes, I have started a series in Hebrew scriptures of stories you think you know, but don’t necessarily know that well. So, I have touched on some of our current issues by examining Abraham’s call when God tells Abraham to go to Canaan, but there is a famine. So he is an “alien” — that is the language that the scripture uses — a “stranger” in Egypt.

We find the scriptures are filled with stories of people going back and forth to and from Egypt to take care of their families. Abraham even says “I can’t take care of my wife Sarai, so we are going to Egypt where we will find food.” We are also going to be accountable for the way we have welcomed (or not welcomed) people.

It’s important for us to be awakened to the fact that welcoming people or not welcoming people is not a new thing. There were what 300,000 Irish people that came to this country during the famine and they were beaten, they were not welcome, they had hard times themselves. The idea of tragic immigrations is not new to our history in the United States.

SP: What message would you want to send to our community during this time when we are struggling with gun violence problems and political problems AND problems with hate and intolerance. One of the reasons I wanted to talk with local faith leaders is because we lay responsibility for so many of our problems at the gates of The White House or the media, but what are we saying to one another at the local level?

Owen: You are really right that it isn’t solely the responsibility of The White House or Congress when they have not taken responsibility to address problems like stopping or curing gun violence. We the public need to be addressing situations locally where we are. We do have the opportunity and ability to steer the course sometimes. We have the privilege as Christians and Americans to speak freely, to make our thoughts known and we need to do that more.

SP: And yet, Reverend, beyond civic engagement, what do we tell our children about how to understand and navigate these times?

Owen: The first thing that comes to mind is that verse about “training up a child in the way that they should go.” The other thing that comes to mind is that when we look at the ministry of Jesus, he conducted ministry in public and I just believe children were there to watch him address difficult issues.

So, in an age-appropriate way, we have to be willing to say that “we are in a tough situation where there are people who don’t want to be kind to one another. But we don’t want to have anyone locked up in a cage, or send his or her family away. Just imagine what it feels like to never be together as a family again.”

When I was a kid, I was really influenced by a book called Blueberry Acres, which was about people who were farmworkers who came to Michigan to pick blueberries. They lived in migrant camps and the children had a really difficult time. Even though it was a children’s book, it was a very sobering book for me. Over time, I decided I wanted to be a migrant nurse so that I could go into the migrant camps and help. And I actually started out in nursing but was then called to ministry.

I know that there are contemporary books written in caring ways for children today so that they can read stories about other children’s concerns. I really don’t believe that we should shield children from these tough issues.

I have been thinking about this regarding the recent Brooklyn shootings. I have a niece and her family live in Brooklyn. And I know that they take their kids to the park. They have a three year old, so if you say you can’t go to the park, the three-year old will ask you “Why can’t we go to the park?” “Why is there yellow tape around the park?” And you have to tell them: “Because someone wants to be hurtful and because we don’t know want anyone else to get hurt, we can’t go right now.”

Our interview ended with Rev. Owen giving me a tour of the building and meeting the summer school staff and campers preparing designing sets for their end-of-camp performance. While black, white, and multiracial youth buzzed around painting and doing set design, one young performer said she had been coming for five summers and an older teen performer said she had been coming for eight summers. Their director joyfully explained the ins and outs of the costumes and shared ideas for expanding the camps.

When we began our interview, Rev. Owen talked about how they were creating a plan to make the church a safe space for the community. And yet, with this kind of long-running, exuberant, diverse community camp, and the messages she delivers to her congregation, it seems they are well on their way.

For more information on service times or programs at St. Peter’s UCC Church, check out their Facebook page.

Photos by Nicole Anderson-Cobb