As When Faith Speaks continues to look for ways that we encounter acts of faith and ambassadors of faith in our daily lives, I wondered about the work of chaplains.

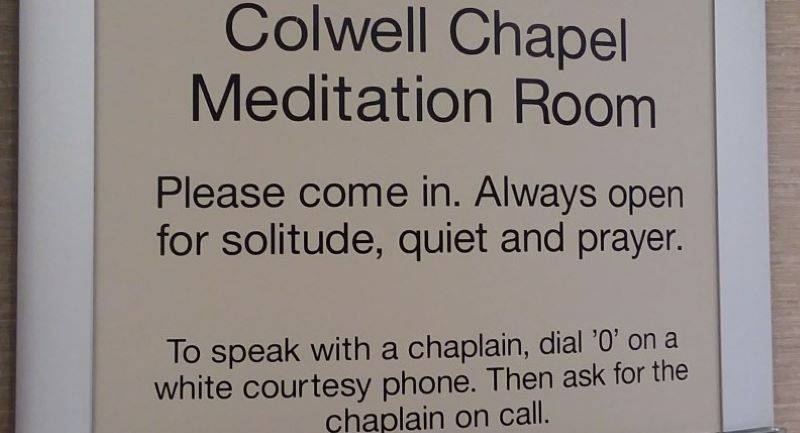

I spoke with Carle Foundation Hospital Chaplain and Pastoral Care Manager Phil McGarvey on his path to chaplaincy and, as McGarvey put it, the daily work of “caring for the sick and dying in Champaign Urbana.” Chaplains at Carle “are available to provide comfort, support, and a listening ear in a way that respects your individual values and choices.”

Smile Politely: How did you know that you wanted to become a chaplain?

Smile Politely: How did you know that you wanted to become a chaplain?

McGarvey: For me, it was kind of an unusual journey. When I was in high school, I kind of knew I wanted to go into ministry, but I wasn’t really good at crisis stuff. Honestly, I would often faint at the sight of blood. So I decided to avoid that kind of ministry. I focused on being a pastor in churches for 20 years… but as I look back, my call to chaplaincy began to grow gradually even then…I went to Denver Seminary, and my first assignment out of seminary was as a youth pastor in Highland, Illinois. Sadly, during my first week of ministry, the senior pastor’s wife got sick and died of an aneurysm. So my first week of ministry, my first assignment was ministry to the pastor’s family.

SP: Sure, of course.

McGarvey: After that, for the first 11 months, he was in grief. I mean we still worked. He still preached, but I really didn’t know what was happening. I was 25 years old and just trying to figure things out.

Additionally, during that time, even though I was a youth pastor, I was doing a lot with the “Senior Saints” or senior citizens in our church, so I got called out to do hospital and nursing home visitation. Often, when people are hospitalized, they fail to notify their pastor that they are in the hospital. However, people always notified me that they wanted me to see them at the hospital.

SP: It sounds like, in spite of your attempt to avoid “crisis stuff,” being called in to serve in medical crisis was always on your radar.

McGarvey: Yep, it was on my radar, but so was my habit of fainting (laughs). I remember a woman who was in my carpool for getting our kids to school. Well, she had to have a kidney transplant. Her sister gave her a kidney at University of Chicago Hospital. I just happened to be visiting the hospital at the exact time that the doctor came in and told her and her mom and dad and her husband that her body was rejecting her sister’s kidney.

SP: Oh my goodness.

McGarvey: The doctor left, and I wasn’t her pastor, but she treated me as a friend and pastor, so I prayed for her. However, as I was praying, I began feeling faint. I thought, “Uh-oh. I know this feeling. This is not good.” Then, at that moment, the nurse happened to walk in at the same time and said “You don’t look good.” She grabbed me by the shoulder and took me out of the room, and I fainted.

SP: Oh, no!

McGarvey (laughing): Again, the fainting kept steering me away from chaplaincy. Sure, I was doing hospital ministry, but I shouldn’t be depending on it, I thought to myself. So, I just kept ministering in churches.

Fast forward a few years and then I got to Streator, IL…the chaplain at the local hospital was needing some help with PRN chaplaincy (“per requested need ministers” are on-call ministers who are not full time, but work when paged).

I worked at that little hospital. At the same time, the church where I was working went through a transition and I didn’t know if I was leaving or staying. The hospital chaplain said “Phil, you’d be a good hospital chaplain. You should think about some training” I said “What training do you get?” Then, she introduced me to clinical pastoral education (CPE) which is kind of the equivalent of a residency or internship in the medical field.

So, I called the supervisor down there (at Bromenn in Normal) and asked “how do I know if I’m called to chaplaincy?”

He gave me an idea of the program offerings and requirements: 1600 hours of CPE which was a year of course work and supervision to become a board certified chaplain.

He also gave me some advice: He said:

“Phil, think about this: Do you want to work with sick and dying patients for eight hours a day, five days a week….for your career? Now, let that sink in: sick and dying patients, all the time, everyday. For 2-3 months, let that resonate in your soul. If you still say yes, that’s me. Well, that’s good. And, if it feels like, uh, I need more life-giving stuff than that. Then, it’s not.”

I went through the thought process he asked me to consider. I thought about it. Prayed about it. Got feedback about it. And I felt that the timing was right for my life.

What I found by doing the CPE is that whether I did become a chaplain or not, CPE was good for my own soul because I would be a better pastor even if I never became a chaplain. The skills you learn in CPE like counseling training, listening, tending to your own soul, discerning the baggage that I bring to the counseling process, finding my footing and balance in counseling with training…So, I signed up, they accepted me, and I went on from there.

SP: You have talked about caring for the sick and dying eight hours a day. What does your day tend to look like?

McGarvey: Typically, if there is no crisis happening, our chaplains at Carle arrive and get their lists of who they need to see, and those protocols vary based on the institution. At some faith-based hospitals like our friends at OSF, the protocols dictate that the chaplain staff visit every patient at some point during their stay. However, here at Carle, we have four full-time chaplains for 400 patients. We all have assigned floors. Each of us are assigned to an ICU unit and additional units. We have a number of criteria that guide our patient visits. Initially we have the patient answer two important questions:

Have you experienced a loss of meaning or joy in your life?

Do you have spiritual struggles currently?

If the patient says anything other than “no” to either of these questions, you are more likely to receive a visit from our staff. Again, this does not guarantee a visit, but it does make a visit more likely during the patient’s stay.

Additionally, we receive orders from doctors or providers who request that we see a particular patient. For example, if a doctor has just given the patient a cancer diagnosis, the doctor may request that we go in and see the person and follow-up with them. We also get phone calls requesting visits to patients as well.

SP: So the chaplain’s priority is a visit to the patient, not the family?

McGarvey: No, just the contrary. Our visits are very much for patients and their families…the patient’s entire environment is important for us to assess. Many times, we are called to visit with the family, not the patient. Technically, our assignment is to care for the patient, family, and the staff serving them.

Especially in a situation where there is a crisis on a floor where they are not used to crisis, we will “round on” (visit for chaplain support) the staff to check in on the staff members in order to provide support during the crisis.

SP: Wow, that is great. I didn’t realize you also provided support to the hospital staff as well.

McGarvey: Yep, that’s part of the mission.

SP: What would you say is the most challenging part of your eight hour day?

McGarvey: I think it might be what we’ve been talking about: deciding who to visit during an eight hour shift.

In some way, almost everyone we visit appreciates that we are there. The challenge is to decide whether, as a former supervisor once said, do you want to make your visits more “intensive” or more “extensive?” Intensive visits mean visits that go deeper and therefore longer. Extensive visits mean visits that go shorter, allowing more patients to be seen. This is a challenge because most chaplains want to go deeper, but we also don’t want to neglect people either. To this end, we depend on great nursing and colleague referrals on the floors to help us prioritize our visits.

That would be the challenging part of a normal day.

I think the challenging part of a crisis is if something happens that is unexpected. An expected death is not necessarily bad. It may be that this person is 95 years old and they had been praying for death so that they could go on and be with their spouse who died five years previously. That may be a “happy” homegoing. Then, there are others like…

SP: An accidental death or a child’s death?

McGarvey: Yeah, those are hard. For instance, in the NICU (Neonatal Intensive Care Unit), you have deaths up there. If the baby dies the day after they are born, yes, it is traumatic. It is always traumatic for the family and for the staff. However, if that baby is in the NICU…and then dies after being in the NICU for six months then everybody, the family and the staff, are in even more grief. Consequently, they are inviting chaplains and our employee assistance people to debrief with the staff to make sure we are talking out our feelings and making sure that they have someone to talk to.

In Labor and Delivery, those crises are hard, too. The hardest thing I have probably seen for me was when a mother died after giving birth. It’s heart-wrenching, just heart-wrenching on everyone. And even at the official staff debrief, people were still reeling two weeks after the mother’s death.

SP: In the midst of all of the routine patient and staff care and crisis care, how do chaplains take care of themselves?

McGarvey: That is a great question. That is the question we continue to ask at the board certifications level. If you can’t take care of yourself, this kind of work isn’t sustainable. Without self care, you are going to treat your other patients poorly…or you will just be a zombie and barely present for them.

However, this self care differs from chaplain to chaplain. For myself, I play ping-pong. One of our other chaplains putzes around with computers. Others have a family and children, so their children help them come back to life during stressful times. Some chaplains work out and rely on physical exercise, prayer, and meditation. Some chaplains take care of themselves with spiritual guides or spiritual directors. Some continue to take courses or are enrolled in some form of self improvement. And some are still involved in church ministry, and that gives us some life back a little bit and reminds us there is a congregation where people are still fully living life.

I also encourage our PRN chaplains that if they are having a really difficult case to bring it up at our staff meeting or we can get together for a meal and debrief together.

SP: What can the public do to support this work since I don’t believe many of us think about the valuable work that chaplains do daily?

McGarvey: Here at Carle we don’t feel that we are doing anything special. We understand this as just part of our mission of care. We understand that our patients want their team of providers to address their spiritual needs so that people are able to lean on their religion when they are sick in the hospital.

Even if people aren’t going to worship, they still have an internal compass of spirituality that they want to hold on to even when they sometimes feel guilty for not attending services in their normal lives. Our goal isn’t to make our patients feel guilty. Our goal is to help them renew their spiritual relationship as they now need to utilize it.

A lot of our ministry is just walking these halls as God’s representatives.

We want to bring patients joy, love, acceptance and grace by showing up and listening to them and holding their space as a sacred space where they can trust what is going on here.

******

A week or so after our interview, I had a nagging question for Chaplain Phil, so I reached out to him for one more response:

SP: Chaplain Phil, how did you finally got over the habit of fainting in hospitals? Did the 1600 hours of training help you to get over the fainting spells? Or do you have another explanation of how you conquered the fainting spells?

McGarvey: After the pastor incident in the Chicago hospital, my primary doctor ran blood tests and found me to be slightly anemic. I started taking a vitamin with iron daily. In addition, I began being more aware of my feelings in emotional situations and could balance them in my mind to separate me from the patient. That continued with the excellent CPE training which helped me normalize hospital situations so that I knew my role and how to help.

By the grace of God, I have had no further incidents.

Photos by Nicole Anderson Cobb