Anyone living on the East Coast right now will likely tell you that to experience polar conditions, all they have to do is open their front door. Those of us not pummeled by snow over the weekend will have to head over to the Spurlock Museum at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Although North of the Northern Lights: Exploring the Crocker Land Artic Expedition: 1913-1917, opened to the public in October 2015, this Wednesday will kick off a series of talks held in conjunction with the exhibit on or related to polar exploration. The first talk, titled “Cook and Peary: Race to the North Pole,” will be led by Sharon Michalove, a retired Adjunct Professor in the Program of Medieval Studies.

At this time of year, temperatures in the Arctic average around negative 30 degrees Fahrenheit. During the summer months when polar explorations begin temperatures can reach 50 degrees. In either case, conditions in the Arctic are extreme and difficult. So you can imagine my surprise when I sat down with Michalove and Elizabeth Watkins, Education and Publications Coordinator of the Spurlock Museum and curator for the exhibit, and they shared with me just how unprepared the men who went on these expeditions were.

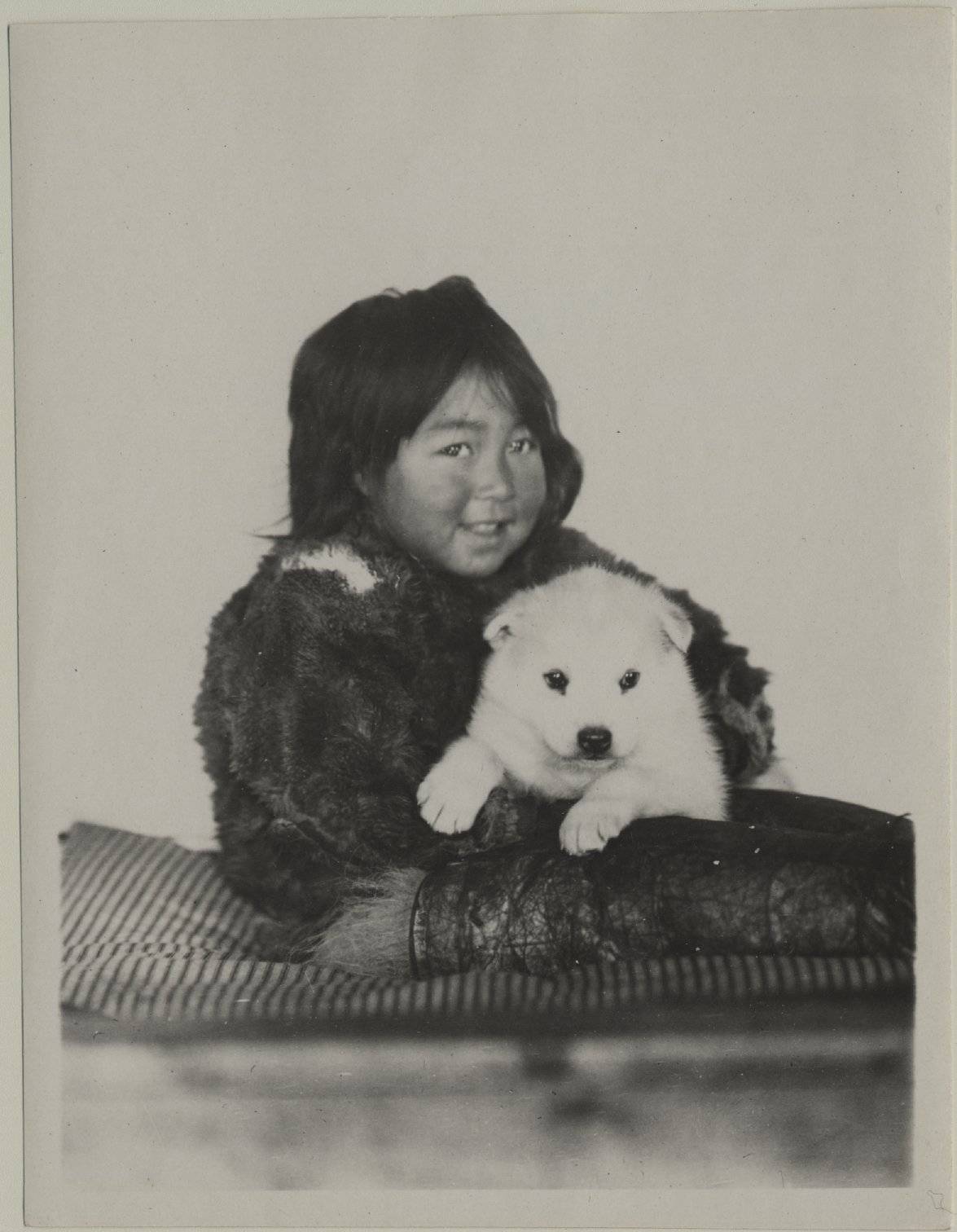

With limited knowledge about the necessary vitamin and calorie intake for a human to survive in extreme conditions, polar explorers planned meals and rations for 3,000-4,000 calories a day. Given the harsh conditions, the explorers burned nearly double that, using around 6,000-7,000 calories a day and were often severely dehydrated. In addition, they were illequipped to clothe themselves properly to handle the freezing temperatures. That and their poor diets, made them largely dependent on the Inuit people, indigenous peoples who inhabited Greenland, Northern Canada, Alaska, and Siberia.

The men who undertook these trips often had no background in polar exploration or science. Many of them were in the U.S. Navy, a frequent sponsor of polar explorations, visited the Arctic for no other reason than to get there. Wholly unprepared for the conditions before them, the men became obsessed, trying again and again. Robert Peary himself went on numerous expeditions, eight of which were in search of the North Pole, and lost almost all of his toes. Peary’s motivations are very clear. In a letter to his mother early on in his polar career, Peary wrote, “My last trip brought my name before the world; my next will give me a standing in the world….I will be foremost in the highest circles in the capital, and make powerful friends with whom I can shape my future instead of letting it come as it will….Remember, mother, I must have fame.” And fame he would have.

In 1906, Peary, intent on recognition and becoming the first to reach the North Pole, was wandering across northeast Canada and saw what he believed were mountains to the west. Continuing on, focused on his search for the Pole, Peary named the mountains Crocker Land after one of his donors, leaving them to be discovered and explored another day.

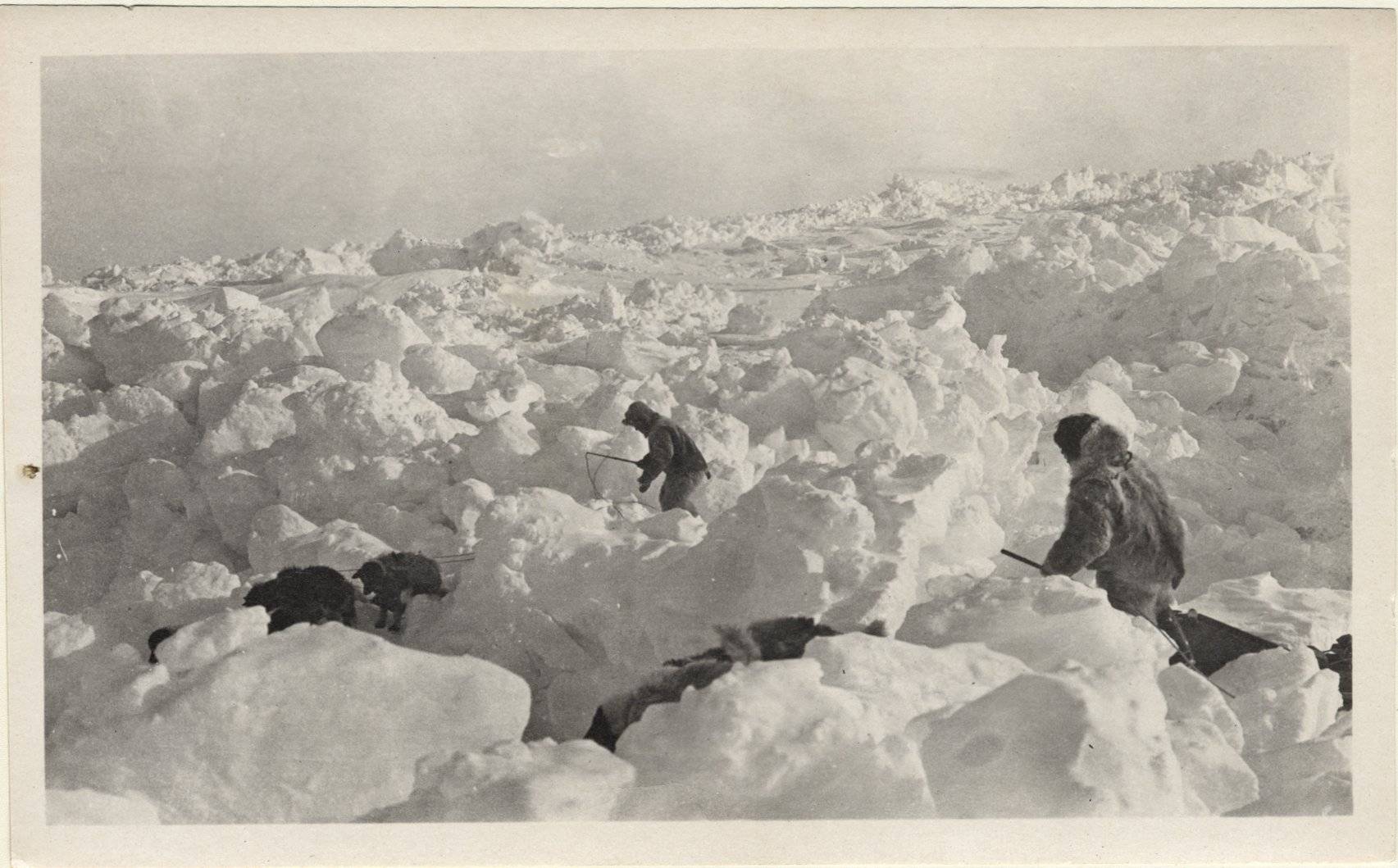

Seven years later the U of I became a co-sponsor, along with the American Museum of Natural History, of an expedition to locate, map, and explore Crocker Land. At the time, to arrive at or escape from the Arctic, explorers had to do so via ship. If conditions were not favorable and there was too much ice, they were stuck, which is exactly what happened to the members of the Crocker Land expedition for two years. What was supposed to be a two-year expedition, from 1913-1915, for two UIUC alums and their fellow explorers turned into four due to the volume of ice encountered. For two years, 1915 and 1916, relief ships could not reach the Crocker Land crew where they were based in northwest Greenland. This year marks the hundredth anniversary of when the Crocker Land expedition was intended to return home.

In the end, the explorers returned from Greenland with the news that Crocker Land was an iceblink, a mirage resulting from light bending differently in changing temperatures, Michalove told me. Though Crocker Land turned out to be an illusion, those on the Crocker Land expedition returned home with scientific data, artifacts, and 4,500 photographs, shared with the U of I as a part of their funding agreement, some of which can be seen at the exhibit. Their prolonged endeavors resulted in invaluable anthropological, geographical, and zoological data.

Now you may be wondering, why wasn’t Peary on the expedition tasked with locating the mountains he “discovered”? For that we have to rewind to 1911 when the United States Congress investigated claims from both Peary and Frederick Cook, each insisting that he had reached the North Pole before the other. Cook and Peary had met years before the race to the North Pole when Cook was assigned as a physician to an expedition of which Peary was a member. Once colleagues, the two men struck by the need to explore the Arctic, became bitter rivals in a quest for notoriety and the Pole. In 1909, within a week of each other, two articles were published stating that Cook and Peary had discovered the North Pole, but not together. Peary claimed to discover the pole in 1909 while Cook claimed to have discovered the pole in 1908, but was unable to tell the world about it because he and his crew were trapped by ice. In the end, the 1911 Congressional investigation ruled that Peary discovered the Pole first. But what if neither Peary, nor Cook, was the first to discover the North Pole? To find out more behind the polarizing controversy surrounding these two men be sure to head to Spurlock Museum this Wednesday, January 27th at 4 p.m. to hear Michalove’s discussion of these events.

To find out more behind the making and findings of the Crocker Land expedition, you can view the exhibit, which is open and free to the public at the Spurlock museum before it closes July 31st.

If you cannot make it to the first talk, there are three more opportunities to learn about more topics on or related to arctic exploration.

On February 24th, Adam Doskey, curator at the Rare Book and Manuscript library will present “Frederick Schwatka: Illinois’s First Arctic Explorer.”

For those more anthropologically inclined, “Norse/Native Contact in Arctic Canada,” is the talk for you, led by Patricia Sutherland of Carleton University and University of Aberdeen, on Thursday, March 10th.

The final topic, with speaker Anna Westerståhl Stenport, will cover changing Arctic conditions in a talk titled, “Greenland, Global Warming, and Contemporary Film and Media Production in the Circumpolar North.” The final talk will be held on Wednesday, April 26th. All talks will talk place at 4 p.m.

If you have any questions about the exhibit, Elizabeth Watkins may be reached via email at ewatkins@illinois.edu.

Interestingly enough, there was a race to the South Pole occurring at the same time as Peary and Cook’s race. Read more about the race to the South Pole here.

Photos courtesy of the American Natural History Museum.