[O]ur thought itself — philosophical, scientific, artistic — is born and shaped in the process of interaction and struggle with others’ thought, and this cannot but be reflected in the forms that […] express our thought as well. — Mikhail Bahktin, Speech Genres and Other Late Essays

We’re used to thinking of technology as new. Somewhere around-ish 1950, the story goes, Alan Turing and computers and stuff happened, and then there was dial-up, and now we’re all shooting straight into a brave, undefined future filled with shiny metal and an irresponsible lack of USB ports.

But all creative work necessarily brings with it elements of the past. On the most basic level, of course, one piece of hardware leads to another, improved version and evolution pushes steadily on.

Cultural critic Mikhail Bakhtin takes it one step further, though. Creative work does not just owe its existence to histories of invention. Instead, history — comprised of the people with whom we’ve interacted and the stories of which we’ve been told — leaves its vivid mark on all that which comes after it. As we build the future, we are also, necessarily, inescapably, rebuilding the past in a different image, out of materials provided to us by those who have gone before.

Urbana artist Eszter Sápi combines art and technology in ways that make this clear. Older, manual technologies like drawing and silkscreen are combined with digital animation to reflect on issues of identity, nationalism, and what it means to find new ways to replay old ideas.

“The experience of motion”: background

Born in Nyíregyháza, Hungary, Sápi was transfixed by the stories of her native country. Once oral tradition, these folktales were eventually turned into books. But old things are adapted to new technologies or die off, and folktales are no exception. They became children’s cartoons that aired on Hungarian national television during Sápi’s childhood.

Animated folktalkes like “A székely asszony és az ördög (The Transylvanian woman and the devil)” were available for children to watch at 7 p.m. every evening. Sápi was hooked. This story is about a woman who always does the opposite of what her husband says, so when he tells her not to jump in a hole, she does and he leaves her there. Desperate for help, she calls for the devil. When he appears, she jumps on his back and rides him around. A soldier appears, and the devil promises to make the soldier a king if he rids him of the woman. The soldier tells the woman to keep riding the devil, and eventually the tormented devil takes possession of a princess, causing her to wiggle around and laugh on her bed while her father looks on and cries. The soldier, ever chivalrous, runs up to the woman on the bed, spreads her legs wide, and shouts into her unmentionables, “Devil, get out of there because I want to get in.” That display of respect and lifelong adoration is taken for what it is — a marriage proposal — and the soldier and princess are hitched. Check out the cartoon on YouTube.

Growing older and wiser, Sápi found that these cartoons were often incredibly violent, regularly featuring rape and beatings as if they were both natural and deserved experiences. And women’s sexuality, she notes, was only appealing if women were possessed by the devil, and fathers and husbands had ultimate control over it. As Sápi contends about the aforementioned cartoon, “the soldier is this huge hero even though he’s going around molesting unknown women.”

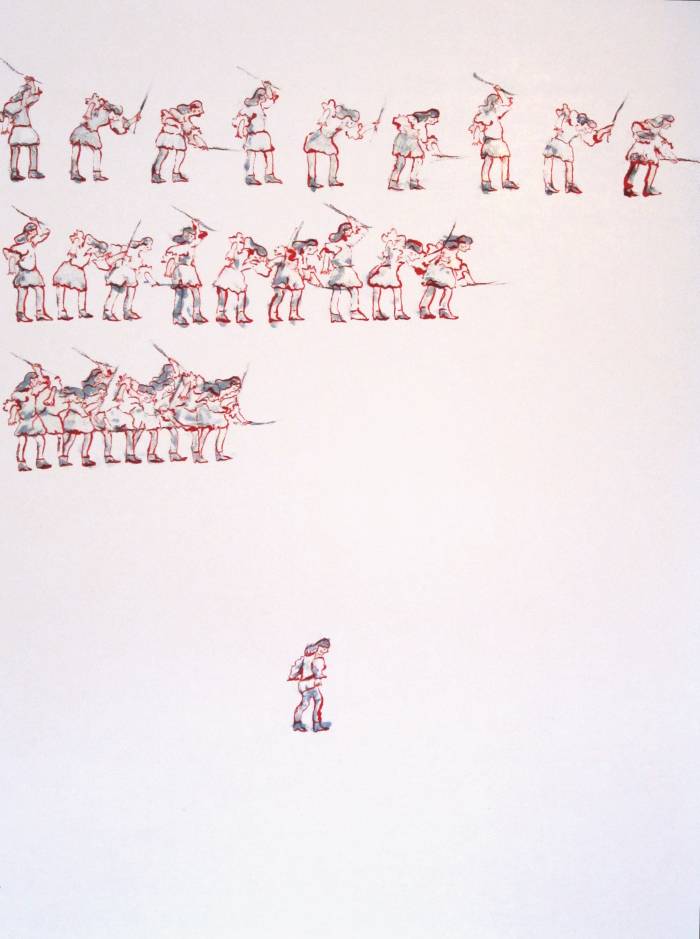

The drawings from her exhibition “The tables have turned” (Urbana Champaign Independent Media Center, 2012) both repeat and rewrite these stories.

The character in this drawing, for example, enacts repetitive violence—the raised arm with a hand clenching a whip, which moves up and down, up and down—but there’s no one to receive the hit. Eventually, the action stops, and the character finds himself alone at the bottom of the page.

Print from “The tables have turned,” an exhibit by Eszter Sápi. Image courtesy of Eszter Sápi.

Sápi has returned to these folktales, with their long history of technological transformation, to work out senses of nationalism, queerness, and displacement to fuel her art and reach out to others in a conversation she’s been having on multiple continents.

Sápi’s work sits where the global and local intersect. Her work has been shown in Belgium, Scotland, and Detroit through the Frans Masereel Centrum Residency program, and throughout central Illinois, including at the Prairie Center of the Arts, the University of Illinois Women’s Resource Center, the Urbana Champaign Independent Media Center, PechaKucha, and Indi Go. She earned her B.A. in Studio Arts from Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota. Sápi then went on to earn an M.F.A. from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University in Boston. After coming to C-U with her partner, a Ph.D. candidate in the History Department at the University of Illinois, Sápi became very active in the local arts community, volunteering with PK and Sky Gallery, and becoming the Director of Indi Go from October 2012 to July 2013.

“You become the press”: work

Though influenced by all of the places she’s been, the impetus for her art is always especially local: it starts with herself. “My work is semi-autobiographical, often coming from personal story or personal memory, of Hungary, of my family, of something horrible someone said on Facebook. Often stuff starts with me being mad,” she says with a laugh, “and then I turn that anger into art to communicate with a larger group. That’s what you do as an artist; that’s our way to communicate.”

Her thesis show in Boston in 2012, “Honvágy; Home Desire/Sickness,” had its root in just such a Facebook fight. Sápi explains:

There was a homophobic and racist attack on social media led by someone whom I know, another Hungarian, and I called this person out on it. The conversation escalated to this person and their friends questioning my Hungarian identity and telling me to never come back to Hungary. I got really mad and created a wall of silk screen to grapple with this. I used abstracted Hungarian folk patterns and an ancient runic alphabet that I had to spend months learning, and I layered silkscreen images on top of sex toys that were shaped as honey pots, a Hungarian slur for recipients of penetration. I was queering what it means to be Hungarian, essentially saying that we can be Hungarian and queer and anti-racist at the same time — to be ethical is not at odds with being a Hungarian.

The medium — here, a wall of static print — matched the message. The wall, Sápi explains, allowed her to tell a story not just about her personal feelings about a Facebook fight (and we all know how heated those things can be). It also allowed her to tell a grand story about history.

“Honvágy; Home Desire/Sickness,” an exhibit by Eszter Sápi. Image courtesy of Eszter Sápi.

Silkscreening is an incredibly repetitive technology where the artist makes a stencil of a desired image, attaches it to a screen, and pushes ink through the screen onto a surface. “You become the press,” Sápi explains, though unlike with a printing press, flawless mass production is impossible. What Sápi calls “the human element” gives every pulled image a slight variation.

Sápi emphasized what happens when the human body combines with mesh and ink in “Honvágy, Home Desire/Sickness.” “I was just laboring away and repeating patterns — runes, stories, honey pots, dildos — until I dreamt them into the very core of my being,” Sápi recalls. It was, needless to say, a profound mix of the very old and the very new. The runic alphabet she taught herself was used when Hungary was a collection of tribes, before it was Christianized in the year 1000, and runes were considered pagan and no longer allowed. They didn’t disappear entirely — nothing ever does, Bahktin would remind us. They migrated into folk culture and became used as personal ornaments.

But now Neo-Nazi groups are starting to claim the alphabet to identify themselves as “real” Hungarians, relying on an ancient past to bolster support for a very modern kind of hate.

“I left some not very nice messages in there for the Neo-Nazis,” Sápi says with a wink. When I asked what they were, she lowered her voice to tell me (though we were alone in my living room) but then said to not print it for Smile Politely. “The people who need to see it will find it.”

Some of Sápi’s stories are indeed only for the 0.0057% or whatever of the entire globe who read ancient Hungarian runes (and if you are among this elite class, you should go pick up what she’s putting down). But other stories are for everybody, regardless of national origin or personal experience.

Sápi’s amazed by how her very personal stories can appeal to so many strangers. “I’ve had several people say, ‘this is my grandmother, that is my family, I recognize this relationship, I know this situation,’” she says with a smile and shake of her head. Even though the stories she’s telling happened thousands of miles — and sometimes thousands of years — away, in languages dead or forgotten or unknown, and are now presented through technologies most people don’t use or understand, people know these stories nevertheless.

Her most recent show, “Something Along Those Lines” (2015, Peoria Art Guild), furthers Sápi’s interest in how silkscreening relates to history by combining it with animation. Silkscreening, at first, seems philosophically at odds with animation: the former creates variation, a general degradation of sharpness and clarity with each pull of the same image, while the latter requires exact reproducibility.

From “Improbable Impossibles,” an exhibit by Eszter Sápi. Image courtesy of Eszter Sápi.

But as in everything she does, Sápi was interested in creating connection between seemingly different and even antithetical things. Silkscreening has the potential to make new and surprising layers with each pull by toying with opacity, much like in PhotoShop. “By decreasing or increasing opacity in PhotoShop, we get different things, and silkscreening is same principle, but it generally takes 50 to 300 pulls to get noticeable differences,” Sápi notes. In animation, though, that time can be compressed to let fuzz and difference rule. “Twelve individual images in one second are required to produce the experience of motion, and most animations are something like 29.97 images per second, so instead of suppressing the fuzz that happens in print, I strung those fuzzy prints together and made motion,” she continues.

Hungarian folk tales remain the starting point of her animation work because they lend themselves to Sápi’s main project of finding patterns in stories and in how people tell them. In layering prints and stringing them together into animations, she can explore the stories we tell ourselves and one another over and over again but on a loop. As Sápi explains:

Animation lets me tell stories without beginning or end. In my video installation, I had two separate short videos that didn’t sync up, and each was running on a loop. After each loop, they would sync up different with each other, creating a new story each time. This is a more complicated queering of these folktales than just switching genders. Animation technology lets me bring new patterns out and focus attention on things unseen before, and let the viewers do the work of making sense of those new things.

“Countdown to Belonging”: future

Where is Eszter Sápi’s work headed? Her majors themes — identity, belonging, nationalism, narrative, community — will remain for some time. But these are affected by what Sápi calls “new configurations,” like installation spaces and technologies available to her. “Sometimes all I can do is draw at my desk and sometimes I am fortunate enough that I am working in a space where they can provide me with two projectors and space and time and an assistant. Thus the different projects, with the same themes.”

From “Improbable Impossibles,” an exhibit by Eszter Sápi. Image courtesy of Eszter Sápi.

But she’d like to hit the online world.

She’s in the process now of creating a site that displays the “mile markers of identity” that she’s calling “Countdown to Belonging.” Throughout her life, she kept setting up goals for when she believed she’d finally feel completely at home in a space, like when she got a degree or a job or a green card. Having achieved all of these things, Sápi is happy but still in pursuit of that elusive sense of complete belonging in a space.

“My next project is to build a website where it would map that experience, where people could contribute to the website and map their own story of belonging — of those markers,” she confides.

Ultimately, in Sápi’s hands, technology — whether it’s screenprinting, animation, or a website — allows us to travel to a place that perhaps doesn’t exist, marking our progress virtually as strangers who nevertheless share in and shape one another’s most fundamental stories.