How can you encourage people of religious faith to associate love of neighbor with love of the earth? One way is by gathering people together to work the soil.

How can you encourage people of religious faith to associate love of neighbor with love of the earth? One way is by gathering people together to work the soil.

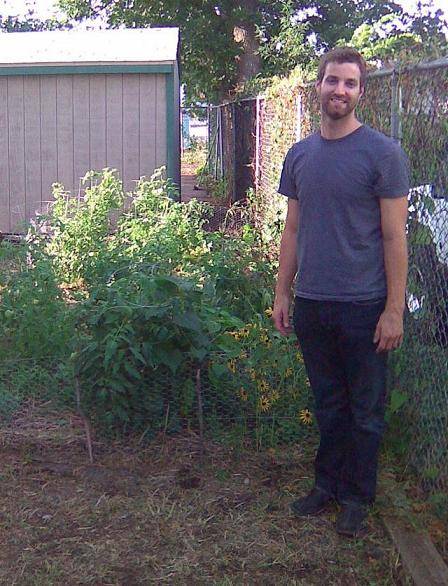

Local spiritual/ecology group EcoEcumenical currently maintains gardens at The 1st Mennonite Church, A Woman’s Fund, and at The Center for Women in Transition and donates the harvest to local charities. However, group leader Brian Sauder explains to me that all this painstaking labor is largely symbolic — it would be more cost effective to just go down to the Farmer’s Market on a Saturday morning and buy the produce.

He elaborates, “We felt that starting community gardens not only captured our desire to promote everyday interaction with the land in a responsible way, but also that participating in the work of community gardens provided numerous spiritual analogies. The combination of the spiritual and the ecological is the focus of our group, and we thought that community gardens captured both of these ideas in both a practical and symbolic manner.”

EcoEcumenical was founded and named by Sauder, who says he isn’t sure of the correct pronunciation of the group name, even though he’s the one who made it up. The group maintains a listserve of around 100 people, some of who show up to work in the community gardens, which are filled with a variety of plants, ranging from strawberries and tomatoes to egg gourds and butterfly weed.

The group brings together volunteers of different faiths. In addition to working in the community gardens, they have discussions about environmental issues, listen to guest speakers, attend advocacy meetings and more. The group is predominantly Christian, although there are participating members who practice the Jewish and Muslim faiths.

EcoEcumenical picked community gardens as its first major project because of the age-old symbolism of gardening. Sauder explains, “There are numerous spiritual analogies associated with gardening. Whether it is tilling the soil, planting seeds, weeding, watering, composting, bearing fruit, etc., all of these activities have obvious spiritual analogies and have been used by religious leaders throughout the ages to describe the joys and struggles of the faith life.”

The EcoEcumenical mission statement reads: “EcoEcumenical brings people together to think and act upon ecological responsibility in the context of their faith communities.”

Sounds good, but I’m curious about something. I ask Sauder why have the “in the context of their faith communities” part at all? If ecological responsibility is something we should all be practicing, why put it in the context of faith communities? Why not frame it in the context of basic self interest — if we don’t practice ecological responsibility, the ice caps are going to melt, we’re all going to suffer, etc.

He responds: “For many people, it is their faith community that informs their worldview. People, myself included, choose to participate in a faith community to find encouragement and accountability to live a life that is honest to an informed religious worldview. Many times in religion, self interest is not the motivator to take action. EcoEcumenical simply seeks to bring ecological responsibility into religious conversation in a way that becomes organic, and thus safe, for the specific religious community.”

As a child, Sauder was raised in an Anabaptist family who practiced a strict form of Christianity. At the same time, he was happily spending hours in the acres of woods behind the family home, immersed in nature.

He grew up to attend the University of Illinois, and his enthusiasm for the outdoors led him to earn a B.S. in environmental science. However, he grew disillusioned with the secular environmental movement: “I quickly learned in college that there is an enormous amount of hypocrisy in environmental circles. Ideology is rarely practiced, and when I realized this for the first time in college, I felt defeated.”

Furthermore, “I was also always overwhelmed with the large scale of our environmental problems. In many ways learning about climate change can be quite the paralytic experience.”

Finally, he decided that a “sense of hope and action” might lie in some kind of common ground between faith and ecology.

“I’ve always had trouble reconciling my experiences in nature with the teachings of Christianity,” he says. It was his desire to correlate these two things that led him to the Urbana Theological Seminary, where he is currently a student pursuing a Masters of Arts Religion with a focus on environmental theology.

Sauder tells me that EcoEcumenical is hoping to reach out especially to conservative Christians like those found in U of I student Christian groups, where members tend to study subjects like Engineering and Agriculture. I ask him if this may be a problem. Aren’t traditional Christians going to associate environmentalism with liberalism — basically that it’s hippie stuff? However, he feels that this barrier can be overcome.

“Environmentalism has negative associations for numerous people, including conservative Christians. It is EcoEcumenical’s hope to allow people of faith to discuss peer-reviewed environmental science in a way that avoids those negative connotations of environmentalism, and allows an adaptation of that peer-reviewed environmental science into a faith community in a way that is honest to that particular faith’s worldview.”

I wonder about the other side of the coin. I guess there’s also a good amount of skepticism among scientists towards the idea of Christians getting involved in environmentalism. After all, some traditional Christians don’t even accept evolution. I ask Sauder if that skepticism is actually the case.

“This skepticism is the case,” he replies, “but easily overcome. E.O. Wilson’s book, The Creation, is a great resource for scientists who are skeptics to people of faith living sustainably.”

Indeed, he feels that many scientists are more than willing to cross ideological lines and reach out to faith communites when it comes to saving the environment. It doesn’t have to be a divisive issue — like abortion, for instance — since everyone’s common good is at stake.

Sauder says, “Most, if not all, environmental scientists realize the large scale of our ecological problems, and they want to see all of humanity, including communities of faith, take action to reverse these problems.”

In any event, even as EcoEcumenical volunteers currently harvest the crops at their community gardens, the group plans, in Sauder’s words, to “continue meeting and discussing ecological responsibility from our own faith perspectives.” They also plan to continue their community gardens next year and to start new projects as well.

The next EcoEcumenical meeting is on September 17th at 6:00 p.m. to discuss an essay on the subject of “Religion and Ecology.” See their website for more details.