In 2018, a group of about 60 people gathered in Mt. Hope cemetery at the University of Illinois for the unveiling of a headstone. The headstone, which marks the life and death of Albert R. Lee, as well as those of his wife and son, sits over ground that is thought to be his final resting place. The location, initially marked by a broken foundation, was discovered due to the work of Lee’s biographer, Vanessa Rouillon. As the inscription on the stone states, Lee was “regarded as dean of African American students at the University of Illinois.” The memorial ceremony was part of a series of events honoring Lee on the 70th anniversary of his death, and 50th anniversary of Project 500.

Photo from The Public i website.

Rouillon writes in a piece for The Public i about standing alongside his grandchildren for the reveal of the new headstone: “This marker, placed among church friends, is dignified in design and size, and thus matches Lee’s sober personality. More permanently, and quite deservingly, this headstone inscribes him in University and local history.”

Photo by Anna Longworth.

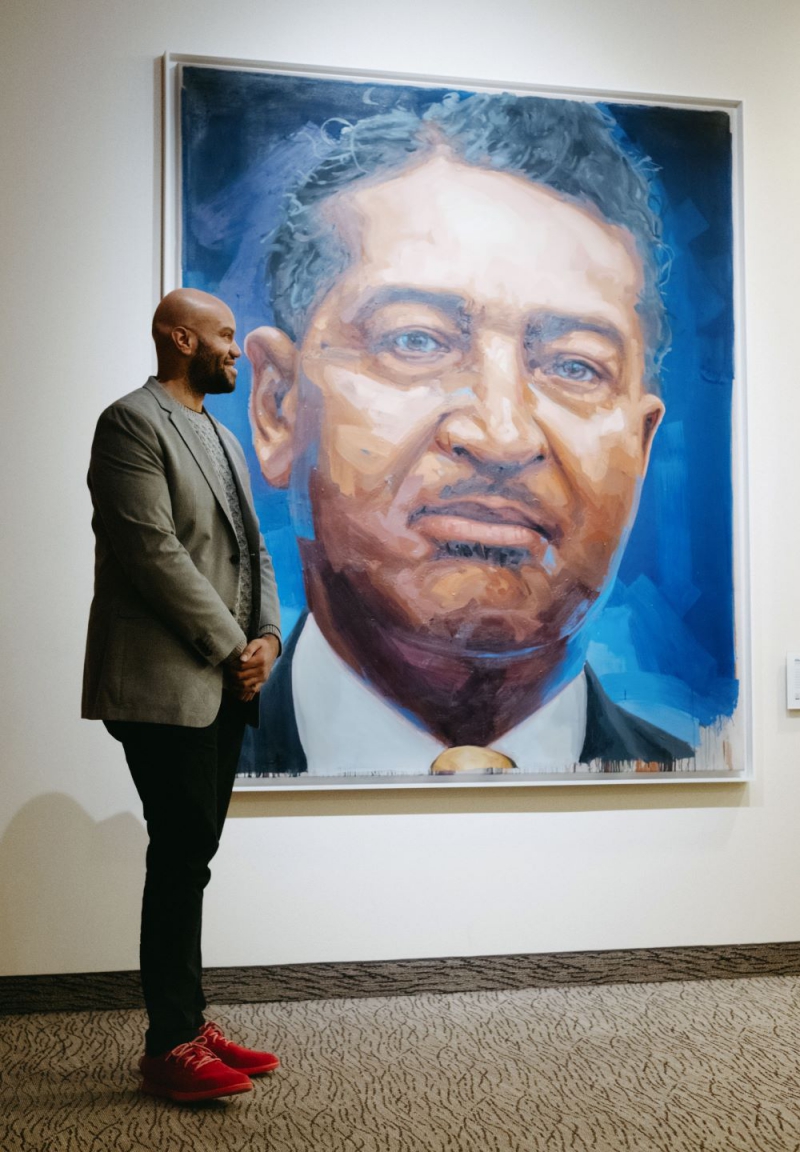

Last week, on the first day of Black History Month, Lee’s legacy became even more permanently enshrined in University history as a portrait of Lee was dedicated in the halls of the Student Dining and Residential Programs building.

Photo by Anna Longworth.

Rouillon was there for this “unveiling” as well, sharing the stage with artist Patrick Earl Hammie, a professor in the School of Art and Design. Hammie was commissioned for the work by Chancellor Robert J. Jones in 2018, following the 2018 recognition.

Photo of U of I President David McKinley and his staff, including Lee. Photo from University of Illinois Archives.

Albert R. Lee was the second African American person to be employed by the University, and while his official roles were mostly clerical in nature — he held the position of Chief Clerk when he retired — his influence among African American students went well beyond the work he was paid to do, earning him the “unofficial dean” title. He was an advocate for Black students, assisting with admissions, housing, employment, and networking, in a time when they did not have the same access as white students. He was also active in the community, as a member of the local NAACP chapter and Bethel A.M.E. church.

Photo from University of Illinois Archives.

In preparing to capture Lee on canvas, Hammie connected with Rouillon to gain insight into the man through photographs and handwritten notes. Rouillon, who received her doctorate in English from U of I, did extensive exploration within the University Archives in her study of Lee. “Through letters he received and wrote [left in the President’s office when Lee retired] you can get a glimpse into the personality of this man. I was captivated by the kind of person he was…The letters showed you the many aspects of his life. He could be strict, he could be warm, he could be honest, he could be fun, he could be serious, he could be thoughtful…I’ve seen the many voices he can inhabit.”

Hammie had the challenging task of bringing all of these characteristics together in one painting. “I wanted him to have the gravity that his role and his legacy carried. I wanted him to have the approachability that many students saw. That complexity and multiplicity of occupying so many positions…the man, the myth, the hero, the advocate, the professional.”

© Patrick Earl Hammie, Albert R. Lee, 2019. Image provided by Patrick Earl Hammie.

Lee died in 1948, so all of the photos of him are in black and white. Hammie felt it was important that the portrait be in color, to feel “alive and current.” He painted the image seven times as he worked through the process of trying to capture Lee, with each of those layers resting beneath the final portrait. If you look closely at the bottom of the painting, you can see pieces of that process, which Hammie intentionally left as part of the portrait.

The vibrant colors bring Lee to life with depth and nuance. He’s distinguished, while his eyes convey the warmth and care Rouillon speaks of, and the resemblence to Lee’s photo is striking in the way it captures his slight smile and kind eyes. The portrait, and its use of color and light, is very much in the style of Hammie’s previous work.

The Student Dining and Residential Programs building was not the original intended home for the portrait. Initially, a more modest portrait was going to hang in a conference room in the Swanlund building, where people would be gathering to make important decisions as Lee “looked on”. However, as Hammie learned more about Lee and the importance of his roles throughout campus, the scale of the project grew, therefore requiring a more suitable space. The next logical possibility was the Bruce Nesbitt African American Cultural Center, but there was not a spot that made sense in their new building.

Photo by Anna Longworth.

It’s final home is a place where student leaders from across campus gather to, as Hammie so poignantly states, “forge their futures and share in the governance of this place. He is still there in conversation with students that he cared for, hopefully inspiring and meeting them where they are.” A significant part of Lee’s work was ensuring equity for Black students, including in housing, which makes this location that much more meaningful. Hammie points out that it hangs near a display detailing the history of housing at the University, a history that excluded Black students. Says Rouillon, “It’s just proper that his image and his memory be among those that he valued so much, among those that he fought for.”