One of the best things about a good academic conference, especially for someone like me who’s not in the academic game and not particularly concerned with “networking,” is sitting in an auditorium and having immensely smart people pour knowledge into your brain. I won’t try to relate what happened with every speaker today, but would highly recommend that you take a look through the video archive when it’s updated next week and watch anything that catches your eye. All of the presentations have been fascinating.

One of the best things about a good academic conference, especially for someone like me who’s not in the academic game and not particularly concerned with “networking,” is sitting in an auditorium and having immensely smart people pour knowledge into your brain. I won’t try to relate what happened with every speaker today, but would highly recommend that you take a look through the video archive when it’s updated next week and watch anything that catches your eye. All of the presentations have been fascinating.

Gillen Wood, associate professor of English and one of the main organizers of the conference, was kind enough to give me some of his time to answer a few questions. The impetus for the creation of the Planet U conference for him was to get more humanists and social scientists to present the facts and implications of climate change. Up to this point, this conversation has been dominated by physical scientists. While they must take the lead on this, as they are doing the research that lets us know what is happening, humanists and social scientists must also be involved in order to help bring the impact of climate change to a human scale and to help weave a narrative that allows our society to take a longer view on the problem.

During one of the afternoon panels, Wood described a nascent project he’s working on that he hopes will model this approach. He’s researching the Tambora volcanic explosion which took place in Indonesia in April, 1815. The blast killed 70,000 to 90,000 people in the immediate area. The sound was audible 2500 km away. Tambora shot 50 to 100 megatons of particulate matter into the stratosphere, six times as much as Mt. Pinatubo in 1991, massively disrupting the wind circulation of the upper atmosphere, radically altering precipitation patterns, and lowering temperatures worldwide over the next two years.

This short-term climate event caused massive crop failures over New England, Western Europe, China, India, and Indonesia. In turn, it precipitated protectionist trade policies, imposition of authoritarian measures like press censorship, famine, and large-scale emigration. (This food shortage was one of many factors affecting Western Europe at the time, as 1815 saw the final fall of Napoleon and the destruction of the ancient regime.) This time is known as the Year of the Beggar in Central Europe. Thankfully, the effect was short-lived, as the particulate dropped out of the atmosphere fairly quickly. The Tambora cooling was over by 1817. Overall, it killed about 500,000 people.

Wood’s project involves some unusual elements. Beyond the typical scholarly book, he is working with the Advanced Visualization Lab at NCSA to create an interactive map built on Google Earth that will link to elaborate simulations of the eruption itself as well as documentary records of its effects worldwide. By using these tools, he hopes to reach toward some of the basic promises of hypertextuality by bringing people into a network of connected facts and stories that help to bring the history to life. Wood said that he found the scientific literature on Tambora rough going. It’s understandable with effort, but his background and training don’t allow him to critically evaluate it. Nevertheless, he believes that humanists and social scientists need to make reading in the hard sciences habitual in order to bring their humanizing perspective to bear on it.

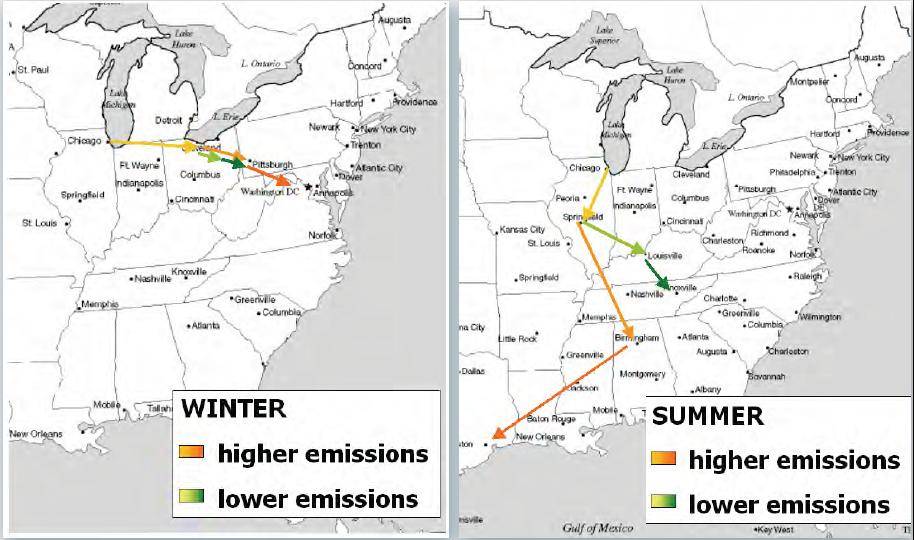

Don Wuebbles, Harry E. Preble Endowed Professor in the Department of Atmospheric Sciences at the U of I and a presenter at the Planet U conference, uses the concept of migrating cities and states as a way of demonstrating the changes that global warming will bring. This picture shows what Chicago’s average temperatures will feel like over the next century. The orange arrows demonstrate the high estimates of the IPCC under which Chicago would feel like Houston during the summer by 2100.

The green arrows show the path under the low IPCC estimates under which Chicago would feel like Knoxville, TN during the summer by 2100.

Calvin DeWitt has approached a similar aim from a different direction over his long career. His focus has been on marrying ecological understanding and concern to Christian thought. The evangelical Christianity that has become so connected to the Republican Party and resistant to the message of climate change has discarded a long history of concern for creation and stewardship in the Christian heritage. DeWitt traced this to the actions of Paul Weyerich, the president of the Heritage Foundation, who worked with Jerry Falwell t o create the Moral Majority and to eviscerate the tradition of Creation stewardship in evangelical churches over the US. DeWitt saw a need for an up-to-date Creation theology, “a biospheric Garden story,” which helps us to understand the Biblical call for reciprocal service with the Earth. As the ecosystem services given to us sustain our lives — what would have in earlier days been known as God’s provenance — so humanity must in turn “avad” (Hebrew for till, cultivate, serve) and “shamar” (Hebrew for keep) the Earth. In DeWitt’s opinion, “the Bible is a green, ecological book.”

o create the Moral Majority and to eviscerate the tradition of Creation stewardship in evangelical churches over the US. DeWitt saw a need for an up-to-date Creation theology, “a biospheric Garden story,” which helps us to understand the Biblical call for reciprocal service with the Earth. As the ecosystem services given to us sustain our lives — what would have in earlier days been known as God’s provenance — so humanity must in turn “avad” (Hebrew for till, cultivate, serve) and “shamar” (Hebrew for keep) the Earth. In DeWitt’s opinion, “the Bible is a green, ecological book.”

As inspiration for creating this narrative, DeWitt invoked Noah’s Ark, a myth that remains true even if it’s not literally correct, in its understanding that the preservation of biodiversity (or as he might put it to an evangelical audience, the abundance of God’s creation) is worth any cost, financial or social. He also appealed to William Blake’s vision in I see the Four-fold Man:

…cruel works

Of many Wheels I view, wheel without wheel, with cogs tyrannic

Moving by compulsion each other, not as those in Eden, which,

Wheel within wheel, in freedom revolve in harmony and peace.

Blake sees here that the little economy of humanity, which we often think of as The Economy, full stop, is but a small wheel compared to the Great Economy of the Earth. To live in “harmony and peace,” we must learn to set our human economy working in concert with the patterns and rhythms of all of Creation (whether you believe in a Creator or not). This requires us to learn a new story about who we are, why we are here, and what it means to live rightly. As DeWitt said, “Learning is required to survive — not just you, but the entire planet. And that’s what makes it exciting.”

The Planet U conference begins its final day at the Beckman Institute today at 9 a.m. You can view the schedule at the conference website.